Science and inventions of Leonardo da Vinci

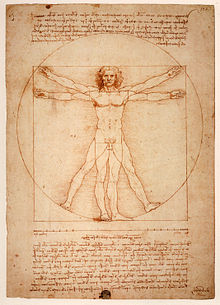

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an Italian polymath, regarded as the epitome of the "Renaissance Man", displaying skills in numerous diverse areas of study.

As an engineer, Leonardo conceived ideas vastly ahead of his own time, conceptually inventing the parachute, the helicopter, an armored fighting vehicle, the use of concentrated solar power, the car and a gun,[1] a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics and the double hull.

[2] In practice, he greatly advanced the state of knowledge in the fields of anatomy, astronomy, civil engineering, optics, and the study of water (hydrodynamics).

[3] As a researcher, Leonardo divided nature and phenomena into ever smaller segments, concretely with knives and measuring instruments, intellectually with formulas and numbers, to wrest the secrets of creation from it.

Capra sees Leonardo's unique integrated, holistic views of science as making him a forerunner of modern systems theory and complexity schools of thought.

Leonardo illustrated a book on mathematical proportion in art written by his friend Luca Pacioli and called De divina proportione, published in 1509.

And if I wished to avoid falling into this fault, it would be necessary in every case when I wanted to copy [a passage] that, not to repeat myself, I should read over all that had gone before; and all the more since the intervals are long between one time of writing and the next.

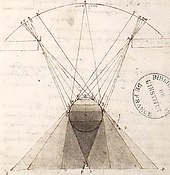

The effects of light on solids were achieved by trial and error, since few artists except Piero Della Francesca actually had accurate scientific knowledge of the subject.

In the painting generally titled The Lady with an Ermine (about 1483) he sets the figure diagonally to the picture space and turns her head so that her face is almost parallel to her nearer shoulder.

These drawings may be linked to a search for the sensus communis, the locus of the human senses,[8] which, by Medieval tradition, was located at the exact physical center of the skull.

However, his depiction of the internal soft tissues of the body are incorrect in many ways, showing that he maintained concepts of anatomy and functioning that were in some cases millennia old, and that his investigations were probably hampered by the lack of preservation techniques available at the time.

His notebooks contain landscapes with a wealth of geological observation from the regions of both Florence and Milan, often including atmospheric effects such as a heavy rainstorm pouring down on a town at the foot of a mountain range.

And a little beyond the sandstone conglomerate, a tufa has been formed, where it turned towards Castel Florentino; farther on, the mud was deposited in which the shells lived, and which rose in layers according to the levels at which the turbid Arno flowed into that sea.

In Leonardo's earliest paintings we see the remarkable attention given to the small landscapes of the background, with lakes and water, swathed in a misty light.

Leonardo produced several extremely accurate maps such as the town plan of Imola created in 1502 in order to win the patronage of Cesare Borgia.

Recent research by Donato Pezzutto suggests that the background landscapes in Leonardo's paintings depict specific locations as aerial views with enhanced depth, employing a technique called cartographic perspective.

In the painting of murals, his experiments resulted in notorious failures with The Last Supper deteriorating within a century, and The Battle of Anghiari running off the wall.

In Leonardo's many pages of notes about artistic processes, there are some that pertain to the use of silver and gold in artworks, information he would have learned as a student.

Leonardo, who questioned the order of the Solar System and the deposit of fossils by the Great Flood, had little time for the alchemical quests to turn lead into gold or create a potion that gave eternal life.

According to Jurgis Baltrušaitis these are some of the oldest examples of anamorphosis known at the time, and with reference to the technique he stated: Vasari in The Lives says of Leonardo: He made designs for mills, fulling machines and engines that could be driven by water-power...

He drew their "anatomy" with unparalleled mastery, producing the first form of the modern technical drawing, including a perfected "exploded view" technique, to represent internal components.

Leonardo wrote to Ludovico describing his skills and what he could build: ...very light and strong bridges that can easily be carried, with which to pursue, and sometimes flee from, the enemy; and others safe and indestructible by fire or assault, easy and convenient to transport and place into position.Among his projects in Florence was one to divert the course of the Arno, in order to flood Pisa.

In 1502, Leonardo produced a drawing of a single span 240 m (720 ft) bridge as part of a civil engineering project for Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II of Istanbul.

[36] Leonardo's letter to Ludovico il Moro assured him: When a place is besieged I know how to cut off water from the trenches and construct an infinite variety of bridges, mantlets and scaling ladders, and other instruments pertaining to sieges.

....If the engagement be at sea, I have many engines of a kind most efficient for offence and defence, and ships that can resist cannons and powder.In Leonardo's notebooks there is an array of war machines which includes a vehicle to be propelled by two men powering crank shafts.

[38] While Leonardo was working in Venice, he drew a sketch for an early diving suit, to be used in the destruction of enemy ships entering Venetian waters.

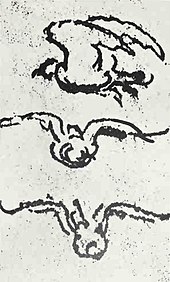

You may see that the beating of its wings against the air supports a heavy eagle in the highest and rarest atmosphere, close to the sphere of elemental fire.

From these instances, and the reasons given, a man with wings large enough and duly connected might learn to overcome the resistance of the air, and by conquering it, succeed in subjugating it and rising above it.

His later journals contain a detailed study of the flight of birds and several different designs for wings based in structure upon those of bats which he described as being less heavy because of the impenetrable nature of the membrane.

Leonardo's original idea, as preserved in his notebooks of 1488–1489 and in the drawings in the Codex Atlanticus, was to use one or more wheels, continuously rotating, each of which pulled a looping bow, rather like a fanbelt in an automobile engine, and perpendicular to the instrument's strings.