Science and technology in Zimbabwe

The economic crisis was accompanied by a series of political crises, including a contested election in 2008, which resulted in the formation of a government of national unity in February 2009.

In parallel, FDI shrank after the imposition of economic sanctions and the suspension of IMF technical assistance due to the non-payment of arrears.

Once stabilized, the economy grew by 6% in 2009, and foreign direct investment (FDI) in Zimbabwe increased slightly; by 2012, it amounted to US$392 million.

[1][2][3] Following a change in government after elections were held in 2013, the Medium Term Plan 2011–2015 was replaced by the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Economic Transformation 2013-2018 (Masset ).

2004) has recognized that the country's industrialization requires a national vision as to which separate materials should be targeted to obtain added value.

Zimbabwe has an agro-based economy, with a growing mining sector: platinum, diamonds, tantalite, silicon, gold, coal, coal-bed, methane, among others.

[4][1] A poll conducted by the World Economic Forum in 2014 determined that lack of finance was a major impediment to promoting innovation and greater competitiveness in Zimbabwe's productive sector, along with policy instability and inadequate infrastructure.

Although the infrastructure is in place to harness R&D to Zimbabwe's socio-economic development, universities and research institutions lack the requisite financial and human resources to conduct R&D and the current regulatory environment hampers the transfer of new technologies to the business sector.

The lack of coordination and coherence among governance structures has also led to a multiplication of research priorities and poor implementation of existing policies.

Despite poor infrastructure and a lack of both human and financial resources, biotechnology research is better established in Zimbabwe than in most sub-Saharan countries, even if it tends to use primarily traditional techniques.

[6][4][1] As a signatory and Party to the SADC Protocol on Science, Technology and Innovation (2008) since 2018, Zimbabwe had committed to raising GERD to at least 1% of GDP by 2020.

This was an ambitious target, given that a national African Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators Survey concluded in 2015 that Zimbabwe’s GERD amounted to less than 0.001% of GDP.

However, the economic crisis has precipitated an exodus of university students and professionals in key areas of expertise (medicine, engineering, etc.)

Likewise, the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Economic Transformation contains no specific targets for increasing the number of scientists and engineers.

The new legislation will require companies to pay a 15% value-added tax but they will incur a 50% discount if they decide to sell their diamonds to the Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe.

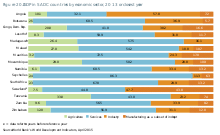

This placed Zimbabwe sixth out of the 15 SADC countries, behind Namibia (59), Mauritius (71), Botswana (103) and, above all, South Africa (175) and the Seychelles (364).

The four sectoral areas are: trade and economic liberalization, infrastructure, sustainable food security and human and social development.

The eight cross-cutting areas are:[2] Targets include:[2] A 2013 mid-term review of the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020 noted that limited progress had been made towards STI targets, owing to the lack of human and financial resources at the SADC Secretariat to co-ordinate STI programs.

In 2013, ministers responsible for the environment and natural resources approved the development of the SADC Regional Climate Change program.