Science diplomacy

[25][26][27] Furthermore, scholars have argued that the definition fails to capture the subtle complexity of the science diplomacy phenomenon or the historical capacity of scientific and diplomatic outcomes to be co-produced.

In the 19th century, the growing specialization of scientific disciplines led experts to hold meetings to standardize methods, practices, and nomenclature.

[39] After World War I, the IAA was reorganized to exclude German scientists due to their support of military actions, including the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three.

[40][41] However, the onset of World War II disrupted cooperation among the scientific communities in the Global North, and meaningful collaboration was only restored in the late 1940s.

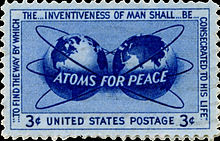

Atoms for Peace and the 1954 Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapons test contributed to Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs intensifying its diplomatic activities on nuclear issues as part of a wider range of science-related activities, including initiating a science attaché program in 1954 and creating a dedicated Science Division in 1958.

[47] The Cold War involved the development of strategic scientific relations as a way to promote cooperation to the extent that it could hedge against diplomatic failures and reduce the potential for conflict, with hegemonic interests informing science diplomacy practices.

[51] The emergence of Cold War power blocs also saw science and technology leveraged as tools for peacefully influencing other nations, particularly in areas like space exploration, geography, and the development of fission reactors.

[55] These collaborations often reflected broader geopolitical shifts, with scientific exchanges serving as both a symbol of ideological alignment and a means of fostering international influence.

Scientists featured prominently in the early exchanges and initiatives that were a part of the Sino-American rapprochement process leading to normalization of relations in 1979.

This broader perspective positions science diplomacy as a form of networked and transnational governance,[62][63] facilitated through platforms such as the United Nations, particularly within specialized agencies like UNESCO.

[65] In collaboration with other international organizations, researchers, public health officials, governments, and clinicians, the WHO works to develop and implement effective strategies for infection control and treatment.

International cooperation has proven instrumental in addressing outbreaks of diseases such as SARS, Ebola, Zika, and continues to play a critical role in managing thechallenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

[68] The second example is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), an engineering megaproject in France, which will be the world's largest magnetic confinement experiment when it begins plasma physics operations.

[69] ITER began in 1985 as a Reagan–Gorbachev initiative with the equal participation of the Soviet Union, the European Atomic Energy Community, the United States, and Japan, with the post-9/11 era posing a challenge on its continuation.

In the late 1990s, several countries joined to establish SESAME with the intention to foster scientific cooperation in a region of the world that has been torn by persistent conflicts.

[74] Particularly in the field of astronomy, Chile had the intention of promoting the concept of a natural laboratory, pointing to the country's good conditions for international scientific research.

For example, the European Union fosters scientific collaboration as a form of diplomacy through "parallel means",[76] with several EU-funded projects.

[79] Another notable example of science diplomacy by non-state actors occurred in 1957, when philanthropist Cyrus Eaton hosted a historic meeting in Pugwash, Canada.

[80] The gathering was inspired by a Manifesto issued by Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein, which called on scientists from all political backgrounds to unite and discuss the existential threat posed by the development of thermonuclear weapons.

Public pressure groups or individuals can have an impact on governmental decisions: For example, the work of Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Review of Literature, helped move the 1963 Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty forward.

[86] Scientists and physicians were also acting beyond state regulation and outside of official diplomatic arenas by researching and exposing the extent of harm done to the Vietnamese people in the war zones.

Science diplomacy, as a tool for conducting diplomatic functions within international relations, reaches beyond human-inhabited territories and plays a key role in expressing competive or collaborative interests in space, oceans, and polar regions.

The treaty emphasized the role of science in managing international spaces beyond sovereign,[97][98] stipulating that parties freeze their territorial claims over Antarctica as long as scientific activities continue.

For proponents of science diplomacy, such as organizations like the RS/AAAS, the Antarctic illustrates that scientific collaboration can foster positive diplomatic outcomes and effective governance of shared spaces.

The treaty helped resolve territorial disputes, particularly between the UK, Argentina, and Chile over overlapping claims in Antarctica, including the contested Antarctic Peninsula.

During the Cold War, countries seeking to collaborate on Antarctic research had to coordinate with the United States, tying scientific cooperation to political alliances.

[105][106] There is also long list of specific themes for science diplomacy to address, including “the rising risks and dangers of climate change, a spread of infectious diseases, increasing energy costs, migration movements, and cultural clashes”.

[61] Other areas of interest include space exploration;[107] the exploration of fundamental physics (e.g., CERN[108] and ITER[109]); the management of the polar regions;[2][110] health research;[111] the oil and mining sectors;[112] fisheries;[113] and international security,[114] including global cybersecurity,[115] as well as enormous geographic areas, such as the transatlantic[62] and Indo-Pacific regions.

[2] Especially within the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, the first calls to begin seeing science and its products as global public goods which should be tasked to fundamentally improve the human condition, especially in countries which are facing catastrophic change, are being made.

Whereas science diplomacy is frequently considered a soft power tool which helps to keep dialogue lines open between states in conflict and can contribute to peacekeeping and international understanding, in times of war, science diplomacy seems to fall within the arsenal of hard power: this became most evident in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.