Screw-cutting lathe

Every degree of spindle rotation is matched by a certain distance of linear tool travel, depending on the desired thread pitch (English or metric, fine or coarse, etc.).

The name "screw-cutting lathe" carries a taxonomic qualification on its use—it is a term of historical classification rather than one of current commercial machine tool terminology.

It is likely that sometimes the wood blanks that they started from were tree branches (or juvenile trunks) that had been shaped by a vine wrapped helically around them while they grew.

Adapting them to screw-cutting is an obvious choice, but the problem of how to guide the cutting tool through the correct path was an obstacle for many centuries.

Not until the late Middle Ages and early modern period did breakthroughs occur in this area; the earliest of which evidence exists today happened in the 15th century and is documented in the Mittelalterliche Hausbuch.

Roughly contemporarily, Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches showing various screw-cutting lathes and machines, one with two leadscrews.

With these, he was able to make an exceptionally accurate dividing engine and in turn, some of the finest astronomical, surveying, and navigational instruments of the 18th century.

Examples were a French mechanic surnamed Senot, who in 1795 created a screw-cutting lathe capable of industrial-level production, and David Wilkinson of Rhode Island, who employed a slide rest in 1798.

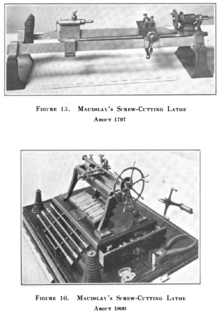

However, these inventors were soon overshadowed by Henry Maudslay, who in 1800 created what is frequently cited as the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, “The outstanding feature of Maudslay’s lathe was a lead screw for driving the carriage.

[6] Bryan Donkin in 1826 took Maudsleys design and refined it further with his screw cutting and dividing engine lathe, which utilised a mechanism for compensating for inaccuracies in the leadscrew.