French Wars of Religion

Moderates, also known as Politiques, hoped to maintain order by centralising power and making concessions to Huguenots, rather than the policies of repression pursued by Henry II and his father Francis I.

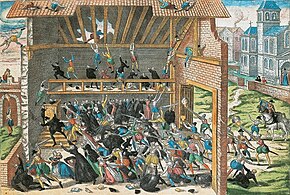

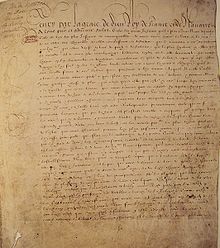

They were initially supported by Catherine de' Medici, whose January 1562 Edict of Saint-Germain was strongly opposed by the Guise faction and led to an outbreak of widespread fighting in March.

[13] In 1495, the Venetian Aldus Manutius began using the newly invented printing press to produce small, inexpensive, pocket editions of Greek, Latin, and vernacular literature, making knowledge in all disciplines available for the first time to a wide audience.

[18] Other members of the Circle included Marguerite de Navarre, sister of Francis I and mother of Jeanne d'Albret, as well as Guillaume Farel, who was exiled to Geneva in 1530 due to his reformist views and persuaded John Calvin to join him there.

This focused on Sola fide, or the idea salvation was a free gift from God, emphasised the importance of understanding in prayer and criticised the clergy for hampering the growth of true faith.

[24] Despite his personal opposition, Francis tolerated Martin Luther’s ideas when they entered France in the late 1520s, largely because the definition of Catholic orthodoxy was unclear, making it hard to determine precisely what was or was not heresy.

[29] The crown continued efforts to remain neutral in the religious debate until the Affair of the Placards in October 1534,[26] when Protestant radicals put up posters in Paris and other provincial towns that rejected the Catholic doctrine of the "Real presence of Christ in the Eucharist".

[50] With the state financially exhausted by the Italian Wars, Catherine had to preserve the independence of the monarchy from a range of competing factions led by powerful nobles, each of whom controlled what were essentially private armies.

[53] A middle path between these two extremes was allowing both religions to be openly practised in France at least temporarily, or the Guisard compromise of scaling back persecution but not permitting toleration.

[57] The Estates then approved the Colloquy of Poissy, which began its session on 8 September 1561, with the Protestants led by de Bèze and the Catholics by Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine, brother of the Duke of Guise.

[60] With their options narrowing, the government attempted to quell escalating disorder in the provinces by passing the Edict of Saint-Germain, which allowed Protestants to worship in public outside towns and in private inside them.

The popular unrest caused by the assassination, coupled with the resistance by the city of Orléans to the siege, led Catherine de' Medici to mediate a truce, resulting in the Edict of Amboise on 19 March 1563.

The crown tried to re-unite the two factions in its efforts to re-capture Le Havre, which had been occupied by the English in 1562 as part of the Treaty of Hampton Court between its Huguenot leaders and Elizabeth I of England.

After Protestant troops unsuccessfully tried to capture and take control of King Charles IX in the Surprise of Meaux, a number of cities, such as La Rochelle, declared themselves for the Huguenot cause.

[78] News of the truce reached Toulouse in April, but such was the antagonism between the two sides that 6,000 Catholics continued their siege of Puylaurens, a notorious Protestant stronghold in the Lauragais, for another week.

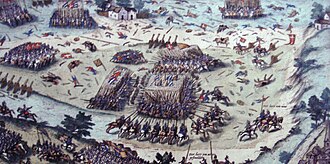

Coligny and his troops retreated to the south-west and regrouped with Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, and in spring of 1570, they pillaged Toulouse, cut a path through the south of France, and went up the Rhone valley up to La Charité-sur-Loire.

[104][105][106] The massacre provoked horror and outrage among Protestants throughout Europe, but both Philip II of Spain and Pope Gregory XIII, following the official version that a Huguenot coup had been thwarted, celebrated the outcome.

The end of hostilities was brought on by the election (11–15 May 1573) of the Duke of Anjou to the throne of Poland and by the Edict of Boulogne (signed in July 1573), which severely curtailed many of the rights previously granted to French Protestants.

A failed coup at Saint-Germain (February 1574), allegedly aiming to release Condé and Navarre who had been held at court since St Bartholemew's, coincided with rather successful Huguenot uprisings in other parts of France such as Lower Normandy, Poitou, and the Rhône valley, which reinitiated hostilities.

Despite having failed to have established his authority over the Midi, he was crowned King Henry III, at Rheims (February 1575), marrying Louise Vaudémont, a kinswoman of the Guise, the following day.

The mediation of Catherine de'Medici led to the Edict of Union, in which the crown accepted almost all the League's demands: reaffirming the Treaty of Nemours, recognizing Cardinal de Bourbon as heir, and making Henry of Guise Lieutenant-General.

[133] During the Estates-General, Henry III suspected that the members of the third estate were being manipulated by the League and became convinced that Guise had encouraged the duke of Savoy's invasion of Saluzzo in October 1588.

The League presses began printing anti-royalist tracts under a variety of pseudonyms, while the Sorbonne proclaimed on 7 January 1589 that it was just and necessary to depose Henry III, and that any private citizen was morally free to commit regicide.

With the aid of the Spanish under Juan del Águila, Mercœur defeated Henry IV's forces under the Duke of Montpensier at the Battle of Craon in 1592, but the royal troops, reinforced by English contingents, soon recovered the advantage; in September 1594, Martin Frobisher and John Norris with eight warships and 4,000 men besieged Fort Crozon, also known as the "Fort of the Lion (El León)" near Brest and captured it on November 7, killing 400 Spaniards including women and children as only 13 survived.

He was formally received into the Catholic Church in 1593, and was crowned at Chartres in 1594 as League members maintained control of the Cathedral of Reims, and, sceptical of Henry's sincerity, continued to oppose him.

[163] The conflict mostly consisted of military action aimed at League members, such as the Battle of Fontaine-Française, though the Spanish launched a concerted offensive in 1595, taking Le Catelet, Doullens and Cambrai (the latter after a fierce bombardment), and in the spring of 1596 capturing Calais by April.

With that victory Henry's concerns then turned to the situation in Brittany where he promulgated the Edict of Nantes and sent Bellièvre and Brulart de Sillery to negotiate a peace with Spain.

Henry and his advisor, the Duke of Sully saw that the essential first step in this was the negotiation of the Edict of Nantes, which to promote civil unity granted the Huguenots substantial rights – but rather than being a sign of genuine toleration, was in fact a kind of grudging truce between the religions, with guarantees for both sides.

Under the 1629 Peace of La Rochelle, the brevets of the Edict (sections of the treaty that dealt with military and pastoral clauses and were renewable by letters patent) were entirely withdrawn, though Protestants retained their prewar religious freedoms.

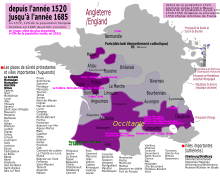

[172] While it did not prompt renewed religious warfare, many Protestants chose to leave France rather than convert, with most moving to the Kingdom of England, Brandenburg-Prussia, the Dutch Republic, Switzerland and the Americas.