Vajrayana

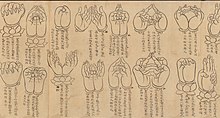

Emerging around the 5th century CE in medieval India, Vajrayāna incorporates a range of techniques, including the use of mantras (sacred sounds), dhāraṇīs (mnemonic codes), mudrās (symbolic hand gestures), mandalas (spiritual diagrams), and the visualization of deities and Buddhas.

The tradition also acknowledges the role of feminine energy, venerating female Buddhas and ḍākiṇīs (spiritual beings), and sometimes incorporates practices that challenge conventional norms to transcend dualistic thinking.

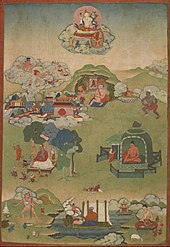

The tradition also employs rich visual imagery, including complex mandalas and depictions of wrathful deities that serve as meditation aids to help practitioners internalize spiritual concepts and confront inner obstacles on the path to enlightenment.

[5] In Japan, Buddhist esotericism is known as Mikkyō (密教, secret teachings) or by the term Shingon (a Japanese rendering of Zhēnyán), which also refers to a specific school of Shingon-shū (真言宗).

The term "Esoteric Buddhism" is first used by Western occultist writers, such as Helena Blavatsky and Alfred Percy Sinnett, to describe theosophical doctrines passed down from "supposedly initiated Buddhist masters.

[2] According to John Myrdhin Reynolds, the mahasiddhas date to the medieval period in North India and used methods radically different from those used in Buddhist monasteries, including practicing on charnel grounds.

[8] Since Tantra focuses on the transformation of poisons into wisdom, the yogic circles came together in tantric feasts, often in sacred sites (pitha) and places (ksetra), which included dancing, singing, consort practices, and the ingestion of taboo substances like alcohol, urine, and meat.

Their rites involved the conjunction of sexual practices and Buddhist mandala visualization with ritual accoutrements made from parts of the human body, so that control may be exercised over the forces hindering the natural abilities of the siddha to manipulate the cosmos at will.

They reinforced their reputations for personal sanctity with rumors of the magical manipulation of various flavors of demonic females (dakini, yaksi, yogini), cemetery ghouls (vetala), and other things that go bump in the night.

Operating on the margins of both monasteries and polite society, some adopted the behaviors associated with ghosts (preta, pisaca), not only as a religious praxis but also as an extension of their implied threats.

[15] Later Mahāyāna texts like the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra (c. 4th–5th century CE) expound the use of mantras such as Om mani padme hum, associated with vastly powerful beings like Avalokiteshvara.

[16] Some of the earliest of these texts, Kriya tantras such as the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa (c. 6th century), teach the use of mantras and dharanis for mostly worldly ends, including curing illness, controlling the weather and generating wealth.

"[28] Sanderson gives numerous examples, such as the Guhyasiddhi of Padmavajra, a work associated with the Guhyasamaja tradition, which prescribes acting as a Shaiva guru and initiating members into Saiva Siddhanta scriptures and mandalas.

According to Wayman, this "Buddha embryo" (tathāgatagarbha) is a "non-dual, self-originated Wisdom (jnana), an effortless fount of good qualities" that resides in the mindstream but is "obscured by discursive thought".

"[43] This view is outlined in the following passage from the Hevajra tantra: Those things by which evil men are bound, others turn into means and gain thereby release from the bonds of existence.

After monks such as Vajrabodhi and Śubhakarasiṃha brought Tantra to Tang China (716 to 720), tantric philosophy continued to be developed in Chinese and Japanese by thinkers such as Yi Xing and Kūkai.

Vajrayāna Buddhism is esoteric in the sense that the transmission of certain teachings occurs only from teacher to student during an empowerment (abhiṣeka), and their practice requires initiation in a ritual space containing the mandala of the deity.

[citation needed] Wayman points out that the symbolic meaning of tantric sexuality is ultimately rooted in bodhicitta and the bodhisattva's quest for enlightenment is likened to a lover seeking union with the mind of the Buddha.

[76] The Tibetologist David Germano outlines two main types of completion practice: a formless and image-less contemplation on the ultimate empty nature of the mind and various yogas that make use of the illusory body to produce energetic sensations of bliss and warmth.

The Cakrasamvara Tantra commentator Kambala, writing about this practice, states: The seats are well-known on earth to be spots within the lotus mandala; by abiding within it there is great bliss, the royal nature of nondual joy.

He notes that the anxiety of figures like Atisa about these practices, and the stories of Virūpa and Maitripa being expelled from their monasteries for performing them, shows that supposedly celibate monastics were undertaking these sexual rites.

[82] Because of its adoption by the monastic tradition, sexual yoga slowly became either done with an imaginary consort visualized by the yogi instead of an actual person, or reserved to a small group of the "highest" or elite practitioners.

[84] The Sanskrit term "vajra" denoted a thunderbolt like a legendary weapon and divine attribute that was made from an adamantine, or an indestructible substance which could, therefore, pierce and penetrate any obstacle or obfuscation.

During this time, three great masters came from India to China: Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra who translated key texts and founded the Zhenyan (真言, "true word", "mantra") tradition.

[113] According to Henrik H. Sørensen describing the Jineon and the Jingak Orders, "they have absolutely no historical link with the Korean Buddhist tradition per se but are late constructs based in large measures on Japanese Shingon Buddhism.

"[114] The first Vietnamese monk we know of who studied Vajrayana was Master Van Ky (c. 7th century) who received initiation in the kingdom of Srivijaya from a certain Jñanabhadra (Tri Hien) as reported by Yijing.

[121][122] This tradition practices and studies a set of tantric texts and commentaries associated with the more "left hand" (vamachara) tantras, which are not part of East Asian Esoteric Buddhism.

In the pre-modern era, Tibetan Buddhism spread outside of Tibet primarily due to the influence of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), founded by Kublai Khan, which ruled China, Mongolia and eastern Siberia.

Bengali Vajrayana scholar Atiśa played a vital role in revitalizing Buddhism in Tibet following its persecution by the Bon emperor Langdarma and onset of the Era of Fragmentation.

Mudrās and mantras, maṇḍalas and cakras, those mysterious devices and diagrams that were so much in vogue in the pseudo-Buddhist hippie culture of the 1960s, were all examples of Twilight Language [...][135]The term Tantric Buddhism was not one originally used by those who practiced it.