Sectarian violence among Christians

Events like the wars which followed the Council of Chalcedon and Constantine's persecution of the Arians caused late antiquity to be considered one of the worst periods of time for a person to be a Christian in.

[3] Andrew Stephenson describes late antiquity as "one of the darkest periods in the history of Christianity" characterizing it as mingling the evils of "worldly ambition, false philosophy, sectarian violence and riotous living.

However, Valen's successor Theodosius I effectively wiped out Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, which condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed.

The Council of Chalcedon was highly influential and marked a key turning point in the Christological debates that broke apart the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries.

His presence initiated a period of fighting in Constantinople between rival bands of monks, Chalcedonian and Non, which ended in AD 511 with the humiliation of Anastasius, the temporary triumph of the patriarch Macedonius II, and the reversal of the Non-Chalcedonian cause (Theophanes, p. 132).

Jonathan Barker cited the Albigensian Crusade, launched by Pope Innocent III against followers of Catharism, as an example of Christian state terrorism.

They worshiped in private houses rather than churches, without the sacraments or the cross, which they rejected as part of the world of matter, and sexual intercourse was considered sinful, but in other respects they followed conventional teachings, reciting the Lord's prayer and reading from Biblical scriptures.

[4] They believed that the Saviour was a "heavenly being merely masquerading as human to bring salvation to the elect, who often have to conceal themselves from the world, and who are set apart by their special knowledge and personal purity".

[4] Cathars rejected the Old Testament and its God, whom they named Rex Mundi (Latin for "king of the world"), whom they saw as a blind usurper who demanded fearful obedience and worship and who, under the most false pretexts, tormented and murdered those whom he called "his children" They proclaimed that there was a higher God—the True God—and Jesus was his messenger.

[15]: 74 When asked by his followers how to differentiate between heretics and the ordinary public, Abbe Arnaud Amalric, head of the Cistercian monastic order, simply said "Kill them all, God will recognize his own!".

[citation needed] In countries where the Reformation was successful, this often lay in the perception that Catholics retained allegiance to a 'foreign' power (the Papacy), causing them to be regarded with suspicion.

Following aggressive Calvinist preaching in and around the rich merchant cities of the southern Netherlands, organized anti-Catholic religious protests grew in violence and frequency.

Starting on 23 August 1572 (the eve of the feast of Bartholomew the Apostle) with murders on orders of the king of a group of Huguenot leaders including Coligny, the massacres spread throughout Paris.

There are records of religious ministers or clerics, politicians, and members of the landed gentry stirring up and capitalizing on sectarian hatred and violence as far back as the late 18th century.

That is far too simple an explanation: it is one which trips readily off the tongue of commentators who are used to a cultural style in which the politically pragmatic is the normal way of conducting affairs and all other considerations are put to its use.

In this context, "Protestants" means essentially descendants of immigrants from Scotland and England settled in Ulster during or soon after the 1690s; also known as "Loyalists" or "Unionist" because they generally support politically the status of Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland has introduced a Private Day of Reflection,[29] since 2007, to mark the transition to a post-[sectarian] conflict society, an initiative of the cross-community Healing through Remembering[30] organisation and research project.

In the time of Elizabeth I, the persecution of the adherents of the Reformed religion, both Anglican and Nonconformist Protestants alike, which had occurred during the reign of her elder half-sister Queen Mary I, was used to fuel strong anti-Catholic propaganda in the hugely influential Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

The passionate intensity of its style and its vivid and picturesque dialogues made the book very popular among Puritan and Low Church families, Anglican and nonconformist Protestant, down to the nineteenth century.

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power in the country; this was seemingly confirmed by various actions by the Vatican.

[31] Anti-Catholicism reached a peak in the mid nineteenth century when Protestant leaders became alarmed by the heavy influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany.

[32] In the 1830s and 1840s, prominent Protestant leaders, such as Lyman Beecher and Horace Bushnell, attacked the Catholic Church as not only theologically unsound but an enemy of republican values.

[36] In the late nineteenth century southern United States evangelical Protestants used a wide range of terror activities, including lynching, murder, attempted murder, rape, beating, tar-and-feathering, whipping, and destruction of property, to suppress competition from black Christians (who saw Christ as the saviour of the black oppressed), Mormons, Native Americans, foreign-born immigrants, Jews, and Catholics.

After the initial attack, several of those who had been wounded or had surrendered were shot dead, and Justice of Peace Thomas McBride was hacked to death by a corn scythe.

The expulsion of several thousand Mormons from Missouri occurred during the winter, which heightened the problems for many of the refugees, who lacked food, shelter, and adequate medicine.

After the destruction of the press of the Nauvoo Expositor, Smith was arrested and incarcerated in the Carthage Jail where he and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob on 27 June 1844.

For a short period of time, the Mormons were forced to establish refugee camps in the plains of Iowa and Nebraska, before pushing further West to the Great Basin in an attempt to completely escape the violence.

Though widely connected with the blood atonement doctrine by the United States press and general public, there is no direct evidence that the massacre was related to "saving" the emigrants by the shedding of their blood (as they had not entered into Mormon covenants); rather, most commentators view it as an act of intended retribution, acted upon due to rumors that some members of this party were intending on joining with American troops in attacking the Mormons.

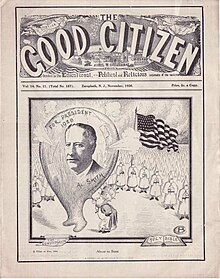

[44] Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics, including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept Catholics from becoming loyal Americans.

After the fall, the Crusaders inflicted a savage sacking on the city[51] for three days, during which many ancient and medieval Roman and Greek works were either stolen or destroyed.