Semang

[5][6] They live in mountainous and isolated forest regions of Perak, Pahang, Kelantan[7] and Kedah of Malaysia[8] and the southern provinces of Thailand.

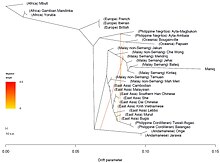

[9] The Semang are among the different ethnic groups of Southeast Asia who, based on their dark skin and other perceived physical similarities, are sometimes referred to by the superficial term Negrito.

For more than one thousand years, some of the Semang people remained in isolation while others were either subjected to slave raids or forced to pay tribute to Southeast Asian rulers.

The Semang live mainly in the more isolated lowlands and foothills within the primary and secondary wet tropical jungles of the northern Malay Peninsula.

In the upper part of the valley, in the Than To District of this province;[32] about 2 km from the Thai-Malaysian border, there is a village in which is the only settled Semang group that lives in Thailand.

The Semang are suggested to be descended from the people of the pre-Neolithic Hoabinhian culture,[40][41][42] which was distributed in Southeast Asia from contemporary Vietnam, to the north eastern part of Sumatra in the 9th-3rd millennium BC.

[44][45] Approximately 4,000 years ago, the practice of Slash-and-burn farming came to the Malay Peninsula, but nomadic hunting and harvesting continued to exist.

[47] On the coast there are settlements, some of them subsequently turned into large ports with permanent populations, consisting of foreign traders who maintained constant ties with China, India, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

The Semang become suppliers of jungle produce, which was in high demand in other countries such as aromatic woods, camphor, rubber, rattan, rhino horns, elephant tusks, gold, tin and so on.

Among the Malaysian sultans and rulers of the southern provinces of Thailand, it was once regarded as prestigious to keep Negritos in their yards as part of collections of amusing jungle beings.

The British perceived the indigenous people as noble savages, who lead an idealized and romantic existence and need protection from the devastating actions of modern life.

[54] Similar actions on the neutralization of the Negritos, albeit on a smaller scale, were also carried out by the Thai government in response to the transfer of communist soldiers into Thailand's territory.

The proclamation of Malaysia's independence in 1957 and the cessation of the Malayan Emergency in 1961 did not bring about significant changes in the state's policy towards the Orang Asli.

In the 1970s, the Department of Orang Asli Affairs began to organize for the Semang settlements, which were meant to relocate several nomadic groups.

Semang believe that their shamans in a state of trance communicate with supernatural beings, can express them gratitude, as well as learn from them the way to treat a serious illness.

The best way is to wait on the grave of the deceased shaman until he appears in the likeness of the tiger, and then he will turn to the person and begin to teach the beginner.

[69][70] The Semang bury their dead on the same day itself with the corpse wrapped in mat and the personal belonging of the deceased kept in a small bamboo rack placed over the grave.

[77] Claims of exclusive rights to a particular area in a dispute with other groups of Semang or with other peoples are usually not put forward and in any case are not valid.

On cleared jungle areas, the state organizes the planting of rubber trees, durian, rambutan, oil palms and bananas.

The Semang are forced to adapt to new conditions, but agricultural activity requires long term waiting results, which contradicts their world view.

Bamboo is used for housing construction, the production of blowguns, darts, fish traps, kitchen utensils, water containers, combs, mats, rafts and ritual items.

The Semang spend a lot of time and effort on harvesting jungle products intended for sale or for exchange with neighboring Malay villages.

[82] Money that the Semang receive from the sale of these goods is then used to buy rice, oil, tobacco, salt, sugar and other food products, as well as clothing, fabrics, knives and other provisions.

[79] Most of the Semang groups grow a certain number of cultivated plants (Upland rice, cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, other vegetables).

Residential groups built by the state under the RPS (Rancangan Pengumpulan Semula, meaning "Regrouping Schemes" in English) have typical Malay-style of wooden huts.

[77] RPS villages are provided with basic infrastructure such as roads, electricity, water supply, medical institutions, and elementary schools.

Now, their more settled lifestyle leads to some groups living in close contact with their own waste, increasing the spread of disease and polluting nearby water supplies.

The family engages in farming together, and at the same time adults teach children the basic skills of management and cultural values of the group.

[93] The rules for avoiding physical contact with the opposite sex, backed up by appropriate taboos, make it impossible for sexual relations outside the family.

Women play an important role in the traditional economy, spending a lot of time harvesting fruits from the jungle and fish from the rivers to provide the family with food.