Cloisonné

Cloisonné (French: [klwazɔne]) is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold.

[1] The decoration is formed by first adding compartments (cloisons in French[2]) to the metal object by soldering or affixing silver or gold as wires or thin strips placed on their edges.

By the 14th century this enamel technique had been replaced in Europe by champlevé, but had then spread to China, where it was soon used for much larger vessels such as bowls and vases; the technique remains common in China to the present day, and cloisonné enamel objects using Chinese-derived styles were produced in the West from the 18th century.

In Middle Byzantine architecture cloisonné masonry refers to walls built with a regular mix of stone and brick, often with more of the latter.

This had been used as a technique to hold pieces of stone and gems tightly in place since the 3rd millennium BC, for example in Mesopotamia, and then Egypt.

[4] The earliest undisputed objects known to use enamel are a group of Mycenaean rings from Graves in Cyprus, dated to the 12th century BC, and using very thin wire.

[5] In the jewellery of ancient Egypt, including the pectoral jewels of the pharaohs, thicker strips form the cloisons, which remain small.

[7] Although Egyptian pieces, including jewellery from the Tomb of Tutankhamun of c. 1325 BC, are frequently described as using "enamel", many scholars doubt the glass paste was sufficiently melted to be properly so described, and use terms such as "glass-paste".

It seems possible that in Egyptian conditions the melting point of the glass and gold were too close to make enamel a viable technique.

[9] Subsequently, enamel was just one of the fillings used for the small, thick-walled cloisons of the Late Antique and Migration Period style.

This type is now thought to have originated in the Late Antique Eastern Roman Empire and to have initially reached the Migration peoples as diplomatic gifts of objects probably made in Constantinople, then copied by their own goldsmiths.

[12] Thick ribbons of gold were soldered to the base of the sunken area to be decorated to make the compartments, before adding the stones or paste.

[13][14] In the Byzantine world the technique was developed into the thin-wire style suitable only for enamel described below, which was imitated in Europe from about the Carolingian period onwards.

The dazzling technique of the Anglo-Saxon dress fittings from Sutton Hoo include much garnet cloisonné, some using remarkably thin slices, enabling the patterned gold beneath to be seen.

Sometimes compartments filled with the different materials of cut stones or glass and enamel are mixed to ornament the same object, as in the Sutton Hoo purse-lid.

[15] From about the 8th century, Byzantine art began again to use much thinner wire more freely to allow much more complex designs to be used, with larger and less geometric compartments, which was only possible using enamel.

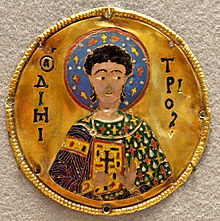

In the Senkschmelz ("sunk" enamel, literally "sunk melt") technique the parts of the base plate to hold the design are hammered down, leaving a surrounding gold background, as also seen in contemporary Byzantine icons and mosaics with gold glass backgrounds, and the saint illustrated here.

[22] Some 10th-century pieces achieve a senkschmelz effect by using two plates superimposed on each other, the upper one with the design outline cut out and the lower one left plain.

This happened during the 11th century in most centres in Western Europe, though not in Byzantium; the Stavelot Triptych, Mosan art of around 1156, contains both types, but the inner cloisonné sections were probably gifts from Constantinople.

[25] In the Renaissance the extravagant style of pieces effectively of plique-à-jour backed onto glass or rock crystal was developed, but was never very common.

In 19th century Japan it was used on pottery vessels with ceramic glazes, and it has been used with lacquer and modern acrylic fillings for the cloisons.

From Byzantium or the Islamic world the technique reached China in the 13–14th centuries; the first written reference is in a book of 1388, where it is called "Dashi ware".

The Chinese industry seems to have benefited from a number of skilled Byzantine refugees fleeing the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, although based on the name alone, it is far more likely China obtained knowledge of the technique from the middle east.

In the Byzantine plaque at right the first feature may be seen in the top wire on the saint's black sleeve, and the second in the white of his eyes and collar.

[32] During the Meiji era, Japanese cloisonné enamel reached a technical peak, producing items more advanced than any that had existed before.

[38] The first Russian cloisonné developed from Byzantine models during the period of Kievan Rus, and has mainly survived in religious pieces.

After all the cloisons are filled the enamel is ground down to a smooth surface with lapidary equipment, using the same techniques as are used for polishing cabochon stones.