Sensationalism

In A History of News, Mitchell Stephens notes sensationalism can be found in the Ancient Roman gazette Acta Diurna, where official notices and announcements were presented daily on public message boards, the perceived content of which spread with enthusiasm in illiterate societies.

According to Stephens, sensationalism brought the news to a new audience when it became aimed at the lower class, who had less of a need to accurately understand politics and the economy, to occupy them in other matters.

A genre of British literature, "sensation novels," became in the 1860s an example of how the publishing industry could capitalize on surprising narrative to market serialized fiction in periodicals.

[citation needed] The attention-grasping rhetorical techniques found in sensation fiction were also employed in articles on science, modern technology, finance, and in historical accounts of contemporary events.

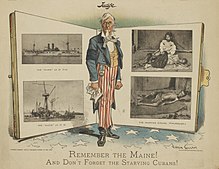

[7] Sensationalism in nineteenth century could be found in popular culture, literature, performance, art history, theory, pre-cinema, and early cinema.

[14][15][better source needed] Sometimes this can lead to a lesser focus on objective journalism in favor of a profit motive,[16] in which editorial choices are based upon sensational stories and presentations to increase advertising revenue.

[2][verification needed] On web-based platforms such as Facebook, Google and YouTube their respective algorithms are used to maximize advertising revenue by attracting and keeping the attention of users.

[26][better source needed] The data scientist Cory Booker suggests that news agencies simply "[speak] the language that resonates with their audience best.

A lesser amount but still significant level is given to court proceedings and the least related to corrections giving the public a limited understand of the criminal justice system and the social contexts of crime.

[35][36] Algorithms that elevate senstional and inflammatory content across a range of platforms including social media, Google, and others have received criticism as fueling division in society.

[37][38] This extends beyond sorting people into echo chambers and filter bubbles to include radicalization by showing more extreme content in order to boost engagement.

[43] Andrew Leonard describes Pol.is as one possible solution to the sensationalism of traditional discourse on social media that has damaged democracies, citing the use of its algorithm to instead prioritize finding consensus.