Set (mathematics)

[5] Before the end of the 19th century, sets were not studied specifically, and were not clearly distinguished from sequences.

Most mathematicians considered infinity as potential—meaning that it is the result of an endless process—and were reluctant to consider infinite sets, that is sets whose number of members is not a natural number.

Together with other counterintuitive results, this led to the foundational crisis of mathematics, which was eventually resolved with the general adoption of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory as a robust foundation of set theory and all mathematics.

In particular, algebraic structures and mathematical spaces are typically defined in terms of sets.

For example, Euclid's theorem is often stated as "the set of the prime numbers is infinite".

This wide use of sets in mathematics was prophesied by David Hilbert when saying: "No one will drive us from the paradise which Cantor created for us.

In mathematical practice, sets can be manipulated independently of the logical framework of this theory.

The object of this article is to summarize the manipulation rules and properties of sets that are commonly used in mathematics, without reference to any logical framework.

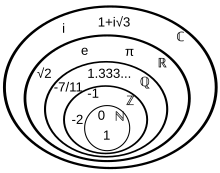

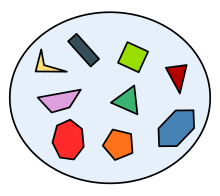

[1][2][3][4] These things are called elements or members of the set and are typically mathematical objects of any kind such as numbers, symbols, points in space, lines, other geometrical shapes, variables, functions, or even other sets.

The natural numbers form an infinite set, commonly denoted

[19] that specifies a set by listing its elements between braces, separated by commas.

When there is a clear pattern for generating all set elements, one can use ellipses for abbreviating the notation,[27][28] such as in

once for all and take the convention that every variable that appears on the left of the vertical bat of the notation represents an element of

For example, with the convention that a lower case Latin letter may represent a real number and nothing else, the expression

The empty set is an identity element for the union operation.

The axioms of these structures induce many identities relating subsets, which are detailed in the linked articles.

For example, structures in abstract algebra, such as groups, fields and rings, are sets closed under one or more operations.

One of the main applications of naive set theory is in the construction of relations.

For example, considering the set S = {rock, paper, scissors} of shapes in the game of the same name, the relation "beats" from S to S is the set B = {(scissors,paper), (paper,rock), (rock,scissors)}; thus x beats y in the game if the pair (x,y) is a member of B.

There are sets of such mathematical importance, to which mathematicians refer so frequently, that they have acquired special names and notational conventions to identify them.

Many of these important sets are represented in mathematical texts using bold (e.g.

Sets of positive or negative numbers are sometimes denoted by superscript plus and minus signs, respectively.

The cardinality of a set S, denoted |S|, is the number of members of S.[37] For example, if B = {blue, white, red}, then |B| = 3.

[30] In fact, all the special sets of numbers mentioned in the section above are infinite.

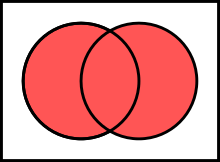

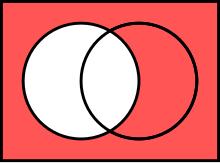

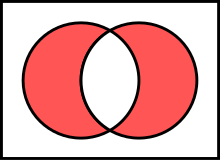

That is, the subsets are pairwise disjoint (meaning any two sets of the partition contain no element in common), and the union of all the subsets of the partition is S.[48][49] The inclusion–exclusion principle is a technique for counting the elements in a union of two finite sets in terms of the sizes of the two sets and their intersection.

The concept of a set emerged in mathematics at the end of the 19th century.

[50] The German word for set, Menge, was coined by Bernard Bolzano in his work Paradoxes of the Infinite.

[51][52][53]Georg Cantor, one of the founders of set theory, gave the following definition at the beginning of his Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre:[54][1] A set is a gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception or our thought—which are called elements of the set.Bertrand Russell introduced the distinction between a set and a class (a set is a class, but some classes, such as the class of all sets, are not sets; see Russell's paradox):[55] When mathematicians deal with what they call a manifold, aggregate, Menge, ensemble, or some equivalent name, it is common, especially where the number of terms involved is finite, to regard the object in question (which is in fact a class) as defined by the enumeration of its terms, and as consisting possibly of a single term, which in that case is the class.The foremost property of a set is that it can have elements, also called members.

[56] The purpose of the axioms is to provide a basic framework from which to deduce the truth or falsity of particular mathematical propositions (statements) about sets, using first-order logic.

According to Gödel's incompleteness theorems however, it is not possible to use first-order logic to prove any such particular axiomatic set theory is free from paradox.

B is a superset of A .