Sétif and Guelma massacre

Both the outbreak and the indiscriminate nature of official and settler retaliation marked a turning point in Franco-Algerian relations, leading to the Algerian War of 1954–1962.

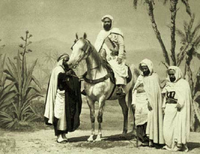

[4] The anti-colonialist movement started to formalize and organize before World War II, under the leadership of Messali Hadj and Ferhat Abbas.

The lack of French reaction led to the creation of the "Amis du Manifeste et de la Liberté" (AML) and eventually resulted in the rise of nationalism.

Contemporary factors other than those of the emergence of Arab nationalism included widespread drought and famine in the rural Constantine Province,[6] where the European settlers were a minority.

In April 1945, growing racial tensions led to a senior French official proposing creation of an armed settler militia in Guelma.

[7] With the end of World War II in Europe, 5,000 protesters took to the streets of Sétif, a town in northern Algeria, to press new demands for independence on the French administration.

A smaller and peaceful protest of Algerian People's Party activists in the neighboring town of Guelma was violently repressed that evening by colonial police, and 12 settlers died in the countryside.

The army, which included Foreign Legion, Moroccan and Senegalese troops, conducted summary executions in the course of a ratissage ("raking-over") of Algerian Muslim rural communities suspected of involvement.

Less accessible mechtas (Muslim villages) were bombed by French aircraft, and the cruiser Duguay-Trouin, standing off the coast in the Gulf of Bougie, shelled Kherrata.

[13] French repression in the Guelma region differed from that in Sétif in that while only 12 pied-noirs had been killed in the countryside, official and militia attacks on Algerian civilians lasted for weeks, until 26 June.

The Constantine préfet, Lestrade-Carbonnel had supported the creation of European settler militias, while the Guelma sous-préfet, André Achiari, created an informal justice system (Comité de Salut Public) designed to encourage the violence of settler vigilantism against unarmed civilians, and to facilitate the identification and murder of nationalist activists.

[20] Nine years later, a general uprising began in Algeria, leading to independence from France in March 1962 with the signing of the Évian Accords.

But it was considered a relatively minor event compared to November 1, 1954, the beginning of the Algerian war for independence; this had legitimized the one-party regime.

The presidency of Liamine Zéroual and Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and the Fondation du 8 Mai 1945, started using the memories of the massacres as a political tool[24] to discuss the consequences of the "colonial genocide"[25] by France.

[29] In February 2005, Hubert Colin de Verdière, France's ambassador to Algeria, formally apologized for the massacre, calling it an "inexcusable tragedy".