Severe plastic deformation

Severe plastic deformation (SPD) is a generic term describing a group of metalworking techniques involving very large strains typically involving a complex stress state or high shear, resulting in a high defect density and equiaxed "ultrafine" grain (UFG) size (d < 1000 nm) or nanocrystalline (NC) structure (d < 100 nm).

[3] This work concerned the effects on solids of combining large hydrostatic pressures with concurrent shear deformation and it led to the award of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1946.

[4] Very successful early implementations of these principles, described in more detail below, are the processes of equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) developed by V.M.

Segal and co-workers in Minsk in the 1970s[5] and high-pressure torsion, derived from Bridgman's work, but not widely developed until the 1980s at the Russian Institute of Metals Physics in modern-day Yekaterinburg.

[4] Some definitions of SPD describe it as a process in which high strain is applied without any significant change in the dimensions of the workpiece, resulting in a large hydrostatic pressure component.

[8] Additionally, some more recent processes such as asymmetric rolling, do result in a change in the dimensions of the workpiece, while still producing an ultrafine grain structure.

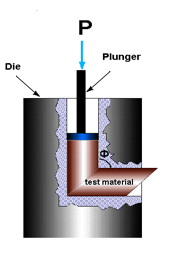

[5] High pressure torsion (HPT) can be traced back to the experiments that won Percy Bridgman the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physics, though its use in metal processing is considerably more recent.

A large compressive stress (typically several gigapascals) is applied, while one anvil is rotated to create a torsion force.

Compared to other SPD processes, ARB has the benefit that it does not require specialized equipment or tooling, only a conventional rolling mill.

[13] Endeavors to improve this technique lead to introduce Repetitive Corrugation and Straightening by Rolling (RCSR), a novel SPD method.

The high frequency results in a large number of collisions between the balls and the surface, creating a strain rate on the order of 102–103 s−1.

The processing is conducted striking a workpiece surface up to 20K or more times per second with shots of an attached ball to the horn in the range of 1K-100K per square millimeter.

This UNSM technique does not only improve the mechanical and tribological properties of a material, but also produces a corrugated structure having numerous of desired dimples on the treated surface.

[23] Most research into SPD has focused on grain refinement, which has obvious applications in the development of high-strength materials as a result of the Hall-Petch relation.

[24][25] Some known commercial application of SPD processes are in the production of Sputtering targets by Honeywell[24] and UFG titanium for medical implants.

Wu et al. describe a process in which dislocation motion becomes restricted due to the small subgrain size and grain rotation becomes more energetically favorable.

[28] Mishra et al. propose a slightly different explanation, in which the rotation is aided by diffusion along the grain boundaries (which is much faster than through the bulk).

This is still useful as it implies that all other things remaining equal, reducing the stacking fault energy, a property that is a function of the alloying elements, will allow for better grain refinement.

[4][7] A few studies, however, suggested that despite the significance of stacking fault energy on the grain refinement at the early stages of straining, the steady-state grain size at large strains is mainly controlled by the homologous temperature in pure metals [30] and by the interaction of solute atoms and dislocations in single-phase alloys.