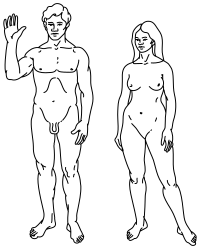

Sexual dimorphism

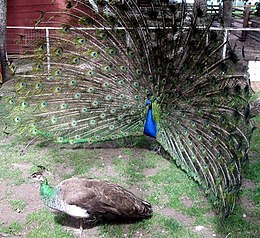

Differences may include secondary sex characteristics, size, weight, color, markings, or behavioral or cognitive traits.

[18][page needed] In redlip blennies, only the male fish develops an organ at the anal-urogenital region that produces antimicrobial substances.

During parental care, males rub their anal-urogenital regions over their nests' internal surfaces, thereby protecting their eggs from microbial infections, one of the most common causes for mortality in young fish.

[citation needed] Insects display a wide variety of sexual dimorphism between taxa including size, ornamentation and coloration.

The selection for larger size in males rather than females in this species may have resulted due to their aggressive territorial behavior and subsequent differential mating success.

In butterfly genera Bicyclus and Junonia, dimorphic wing patterns evolved due to sex-limited expression, which mediates the intralocus sexual conflict and leads to increased fitness in males.

[41] The sexual dichromatic nature of Bicyclus anynana is reflected by female selection on the basis of dorsal UV-reflective eyespot pupils.

In fish, reproductive histories often include the sex-change from female to male where there is a strong connection between growth, the sex of an individual, and the mating system within which it operates.

Females experience minor changes in snout length, but the most noticeable difference is the huge increase in gonad size, which accounts for about 25% of body mass.

[59] Since carotenoid-based ornamentation suggests mate quality, female two-spotted guppies that develop colorful orange bellies during breeding season are considered favorable to males.

[60] The males invest heavily in offspring during incubation, which leads to the sexual preference in colorful females due to higher egg quality.

[citation needed] Anole lizards show prominent size dimorphism with males typically being significantly larger than females.

[63] The development of color dimorphism in lizards is induced by hormonal changes at the onset of sexual maturity, as seen in Psamodromus algirus, Sceloporus gadoviae, and S. undulates erythrocheilus.

[64] Male breeding coloration is likely an indicator to females of the underlying level of oxidative DNA damage (a significant component of aging) in potential mates.

When the environment gives advantages and disadvantages of this sort, the strength of selection is weakened and the environmental forces are given greater morphological weight.

The sexual dimorphism could also produce a change in timing of migration leading to differences in mating success within the bird population.

[83] The term sesquimorphism (the Latin numeral prefix sesqui- means one-and-one-half, so halfway between mono- (one) and di- (two)) has been proposed for bird species in which "both sexes have basically the same plumage pattern, though the female is clearly distinguishable by reason of her paler or washed-out colour".

[86]: 245 Examining fossils of non-avian dinosaurs in search of sexually dimorphic characteristics requires the supply of complete and articulated skeletal and tissue remains.

Crocodilian skeletons were examined to determine whether there is a skeletal component that is distinctive between both sexes, to help provide an insight on the physical disparities between male and female theropods.

Ceratopsians According to Scott D. Sampson, if ceratopsids were to exhibit sexual dimorphism, modern ecological analogues suggest it would be found in display structures, such as horns and frills.

[87] In addition, many sexually dimorphic traits that may have existed in ceratopsians include soft tissue variations such as coloration or dewlaps, which would be unlikely to have been preserved in the fossil record.

According to Clark Spencer Larsen, modern day Homo sapiens show a range of sexual dimorphism, with average body mass between the sexes differing by roughly 15%.

Additionally, they produce more antibodies at a faster rate than males, hence they develop fewer infectious diseases and succumb for shorter periods.

[116] The brains of pregnant females carrying male fetuses may be shielded from the masculinizing effects of androgen through the action of sex hormone-binding globulin.

In addition, it has been shown that genes with sex-specific expression undergo reduced selection efficiency, which leads to higher population frequencies of deleterious mutations and contributes to the prevalence of several human diseases.

[137] The interaction between the sexes and the energy needed to produce viable offspring makes it favorable for females to be larger in this species.

The fecundity advantage hypothesis states that a larger female is able to produce more offspring and give them more favorable conditions to ensure their survival; this is true for most ectotherms.

A male must find a female and fuse with her: he then lives parasitically, becoming little more than a sperm-producing body in what amounts to an effectively hermaphrodite composite organism.

[139] This is taken to the logical extreme in the Rhizocephala crustaceans, like the Sacculina, where the male injects itself into the female's body and becomes nothing more than sperm producing cells, to the point that the superorder used to be mistaken for hermaphroditic.

Volvocine algae have been useful in understanding the evolution of sexual dimorphism[154] and species like the beetle C. maculatus, where the females are larger than the males, are used to study its underlying genetic mechanisms.