Sex ratio

These include parthenogenic and androgenetic[3] species, periodically mating organisms such as aphids, some eusocial wasps, bees, ants, and termites.

His argument was summarised by W. D. Hamilton (1967)[2] as follows, assuming that parents invest the same whether raising male or female offspring: In modern language, the 1:1 ratio is the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS).

A study performed by Danforth observed no significant difference in the number of males and females from the 1:1 sex ratio.

A herd of cows with a few bulls or a flock of hens with one rooster are the most economical sex ratios for domesticated livestock.

[citation needed] It was found that the amount of fertilizing pollen can influence secondary sex ratio in dioecious plants.

This relationship was confirmed on four plant species from three families – Rumex acetosa (Polygonaceae),[19][20] Melandrium album (Caryophyllaceae),[21][22] Cannabis sativa[23] and Humulus japonicus (Cannabinaceae).

[24] In charadriiform birds, recent research has shown clearly that polyandry and sex-role reversal (where males care and females compete for mates) as found in phalaropes, jacanas, painted snipe and a few plover species is clearly related to a strongly male-biased adult sex ratio.

[26] Male-biased adult sex ratios have also been shown to correlate with cooperative breeding in mammals such as alpine marmots and wild canids.

[25] It is known, however, that both male-biased adult sex ratios[29] and cooperative breeding tend to evolve where caring for offspring is extremely difficult due to low secondary productivity, as in Australia[30] and Southern Africa.

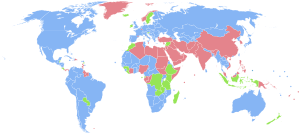

|

Countries with more

males

than females.

Countries with the

same

number of males and females (accounting that the ratio has 3

significant figures

, i.e., 1.00 males to 1.00 females).

Countries with more

females

than males.

No data

|