Sexism in American political elections

[4] Although patriarchy is the dominant cultural practice in the United States, sexism exists as a process within this system that can also function separately and reward feminine behavior or appearance.

[8] Although social factors can greatly influence the relationship between women and politics, institutions and systemic processes can also enable gendered results, and the election context also affects behavior.

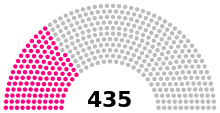

[9] Other politically marginalized groups in the United States, specifically racial and ethnic minorities, face similar obstacles as women when trying to achieve proportionate representation.

While there are some electoral mechanisms, such as gerrymandering, that can offer a higher likelihood of at least some representation for these groups, this benefit does not extend to women as a demographic, as they are not similarly concentrated in certain geographic areas.

[12] Daniel M. Thomsen and Aaron S. King also make notes on the candidate political pool that there are nearly triple the amount of men running for candidacy in each party versus women.

Studies have found that a person's sex is one of many significant predictors of likelihood to consider running for office, with men 50% more likely than women to engage in pre-campaign activities, such as learning about registration and other candidacy basics, even when accounting for differences in careers.

[14] This disparity stems from a variety of factors, including perceptions among women that they would be more likely to face hostile sexism in the forms of voter hesitancy, lack of fair media coverage, or fundraising issues.

[32][31] Female candidates tend to also be viewed as more caring compared to their male counterparts on certain issues, such as defense and the military, which can result in disadvantages for women when a topic is thought of as 'owned' by men.

For example, in the 2016 presidential election, terrorism and national security were top priorities to the American public—possibly making it more difficult for female candidates to gain support around these issues.

[37] Sexism can be expressed through both implicit and explicit means; this is reflected in how people view women in positions of authority, including female political candidates.

[46] As the head of the Executive Branch, presidents have access to an extraordinary number of governmental abilities, including nominating Supreme Court Justices and vetoing bills passed by Congress; moreover, this position carries with it a symbolic and legitimate connection to the informal establishment of patriarchy.

[52] Research has also found that voters put more value in qualities seen as masculine and rank male candidates as more effective than their female counterparts who are similarly qualified.

The Barbara Lee Family Foundation advised a “powerful yet approachable” look in a guidebook meant for female candidates, pointing to women's need to balance traits viewed as masculine and feminine.

Clinton, as the first female candidate to be nominated by one of the two major political parties, received a great deal of sexist portrayals and rhetoric from the media, as well as Trump's Campaign.

[57] While several factors can explain this difference, the researchers argue that it is a result of how sexism pushes the most ambitious and talented women to pursue, and subsequently win, elected office.

One study found that when increased representation occurred alongside greater female labor force participation, there was an association with higher levels of spending on family benefits.

[60] Throughout the article, he theorizes that a lack in elite support in campaign funding is contributing to this gap, since Republican women on average fundraise slightly less money than their male counterparts.

With similar findings that support Bucchianeri's work, an article by Danielle Thomsen and Michael Sewers also concludes that women running electoral campaigns tend to have smaller donor networks than men.

Recent research highlights the strategic behavior of female candidates in navigating electoral processes shaped by gender norms and sexism.

For instance, Lawless and Fox (2018) discuss how perceived electoral environments influence women's decisions to enter races, particularly highlighting the impact of sexism on these perceptions.

[63] This aligns with findings from Bucchianeri (2018), who notes that female candidates, especially in the Republican Party, tend to encounter and must navigate additional challenges such as reduced fundraising and support from political elites.

[64] In a study conducted by Jordan Mansell, Allison Harell, Melanee Thomas, and Tania Gosselin, we also see obstacles with men having a negative reaction towards women when they are more successful than them.

[65] Furthermore, Thomsen and Swers (2017) explore the gendered nature of candidate donor networks, revealing that women often face a narrower pathway to securing necessary campaign funds, which are crucial for electoral success.

Sorenson and Chen (2022) provide a comprehensive analysis of campaign finance data, demonstrating that women of color are particularly disadvantaged, receiving less funding compared to their white and male counterparts, which affects their visibility and viability as candidates.