Shakespeare apocrypha

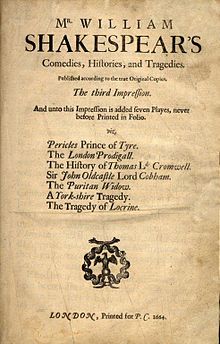

Several plays published in quarto during the seventeenth century bear Shakespeare's name on the title page or in other documents, but do not appear in the First Folio.

In some cases, the title page attributions may be lies told by fraudulent printers trading on Shakespeare's reputation.

Another explanation for the origins of any or all of the plays is that they were not written for the King's Men, were perhaps from early in Shakespeare's career, and thus were inaccessible to Heminges and Condell when they compiled the First Folio.

In 1796 William Henry Ireland claimed to have found a lost play of Shakespeare entitled Vortigern and Rowena.

Jaggard issued an expanded edition of The Passionate Pilgrim in 1612, containing additional poems on the theme of Helen of Troy, announced on the title page ("Whereunto is newly added two Love Epistles, the first from Paris to Hellen, and Hellen's answere back again to Paris").

Heywood protested the unauthorized copying in his Apology for Actors (1612), writing that Shakespeare was "much offended" with Jaggard for making "so bold with his name."

It was first attributed to Shakespeare by American scholars William Ringler and Steven May, who discovered the poem in 1972 in the notebook of Henry Stanford, who is known to have worked in the household of the Lord Chamberlain.

[18] In 1989, using a form of stylometric computer analysis, scholar and forensic linguist Donald Foster attributed A Funeral Elegy for Master William Peter,[19] previously ascribed only to "W.S.

Later analyses by scholars Gilles Monsarrat and Brian Vickers demonstrated Foster's attribution to be in error, and that the true author was probably John Ford.

[21][22] This nine-verse love lyric was ascribed to Shakespeare in a manuscript collection of verses probably written in the late 1630s.

[23] Shakespeare has been identified as the author of two epitaphs to John Combe, a Stratford businessman, and one to Elias James, a brewer who lived in the Blackfriars area of London.

This is recorded in several variant forms in the 17th and 18th centuries, usually with the story that Shakespeare composed it extempore at a party with Combe present.

"[26] Building on the work of W. J. Courthope, Hardin Craig, E. B. Everitt, Seymour Pitcher and others, the scholar Eric Sams (1926–2004), who wrote two books on Shakespeare,[27][28] edited two early plays,[29][30] and published over a hundred papers, argued that "Shakespeare was an early starter who rewrote nobody's plays but his own", and that he "may have been a master of structure before he was a master of language".

[32] As many of the Quarto title-pages proclaim, Shakespeare was an assiduous reviser of his own work, rewriting, enlarging and emending to the end of his life.

[33] He "struck the second heat / upon the Muses' anvil," as Ben Jonson put it in the Folio verse tribute.

Sams dissented from 20th-century orthodoxy, rejecting the theory of memorial reconstruction by forgetful actors as "wrong-headed".

"[34] The few unofficial copies referred to in the preamble to the Folio were the 1619 quartos, mostly already superseded plays, for "Shakespeare was disposed to release his own popular early version[s] for acting and printing because his own masterly revision[s] would soon be forthcoming".

[36] Sams also rejected 20th century orthodoxy on Shakespeare's collaboration, arguing that, with the exception of Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII, and Two Noble Kinsmen, the plays were solely his, though many were only partly revised.

[42] Sams also argued, more briefly, that "there is some evidence of Shakespearean authorship of A Pleasant Commodie of Fair Em the Millers Daughter, with the loue of William the Conqueror, written before 1586, and of The Lamentable Tragedie of Locrine written mid-1580s and "newly set foorth, ouerseene and corrected, by W.S."