Shamanism during the Qing dynasty

His son and successor Hong Taiji (1592–1643), who renamed the Jurchens "Manchu" and officially proclaimed the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in 1636, further put shamanistic practices in the service of the state, notably by forbidding others to erect new tangse (shrines) for ritual purposes.

In 1644, as soon as the Qing seized Beijing to begin their conquest of China proper, they named it their new capital and erected an official shamanic shrine there.

Partly because of their secret aspect, these rituals attracted the curiosity of Beijing dwellers and visitors to the Qing capital.

Historians are now arguing that shamanistic practices in northeast Asia were intimately tied to the establishment of states, an analysis that fits the Qing case very well.

[2] The most common religion among the Manchus was shamanism, which they and their ancestors the Jurchens practiced long before the Qing dynasty expanded into China proper.

[6] The shaman (often a woman) was in charge of placating spirits and dead ancestors and of contacting them to seek a good hunt or harvest, quick healing, success in battle, and other such favors.

[11] "Primitive ritual", on the other hand, was performed by people who had undergone a "shamanic illness", which was seen as a sign that they had been chosen by the spirits.

[20] He worshipped Heaven at a shamanic shrine in 1593 before leaving for a campaign against the Yehe, a Jurchen tribe that belonged to the rival Hūlun confederacy.

[20] Qing annals also report that when Nurhaci announced his Seven Great Grievances against the Ming dynasty in April 1618, he conducted a shamanic ceremony during which he burned an oath to Heaven written on a piece of yellow paper.

[23] Nurhaci's son Hong Taiji (r. 1626–1643), who renamed the Jurchens "Manchus" in 1635, forbade commoners and officials from erecting shamanic shrines for ritual purposes, making the tangse "the monopoly of the ruler".

[31] The tangse was destroyed in 1900 by foreign powers in the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising as part of reprisals for the two-month siege of the international Legation Quarter.

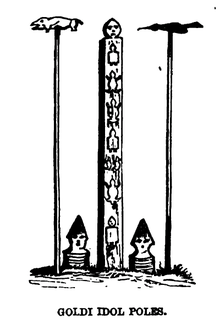

[35] This palace had served as the Empress's residence under the Ming dynasty, but the Qing converted it for ritual use, installing a "spirit pole" to present sacrifices to heaven, changing the style of the windows, and setting up large cauldrons to cook sacrificial food.

[28] The Qing emperor used shamanism to promote the dynasty's legitimacy among the Tungusic peoples such as the Evenks, Daur and Oroqen who lived near the northeastern borders of the empire.

[14] In 1649 Dorgon's brother Dodo, who had helped the Qing conquer southern China in 1645, fell ill with smallpox, a highly contagious disease that the Manchus particularly dreaded.

[14] In the 1740s, the Qianlong Emperor worried that shamanic traditions were becoming lost, especially among the Manchu Bannermen who lived in garrisons throughout the empire.

[58] Historian Pamela Crossley sees it as part of the Qianlong Emperor's attempts to "standardize the cultural and spiritual life of the Manchus", taking the practices of the imperial clan as a model.

[59] Though the Shamanic Code was first kept in manuscript form, French Jesuit Joseph-Marie Amiot had a study on it, Rituels des Tartares Mandchous déterminés et fixés par l'empereur comme chef de sa religion, published in Amsterdam in 1773.

[61] The Manchu version was printed in 1778, whereas the Chinese-language edition, titled Qinding Manzhou jishen jitian dianli (欽定滿洲祭神祭天典禮), was completed in 1780 or 1782.

[65] We know that after the publication of the "Shamanic Code" some clans (like the Šušu) and tribes (like the Xibe) also wrote down their rituals and incantations, showing that the court model was not always followed.

[69] Both Chinese and Manchu heaven were an "all-encompassing principle of cosmic order and human destiny" that could be used to give the state legitimacy.

Guandi and the bodhisattva (Buddhist "enlightened being") Guanyin were two of a "handful of Chinese gods" who were integrated into the rituals of the state tangse and Kunning Palace.

[72] Ordinary Manchu households rarely sacrificed to Buddhist deities, but almost all of them worshipped Guandi because of his association with war.

[78] According to historian Pamela Kyle Crossley, proficiency with shamanism was among the qualities that the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) promoted as being part of the "Old Way" (fe doro) of the Manchus when he attempted to formalize the Manchu heritage late in his reign.

[81] Nonetheless the persistence of shamanistic practices at the Qing court into the twentieth century suggests that the Manchus were not automatically "sinicized" by the sole fact that they ruled over China.

[77] Ethnic Han residents and visitors, who were forbidden to observe the rituals performed at the shamanic shrine, saw these rites as "different and mysterious" or "secret and alien".

[85] Writers who wanted to satisfy their readers' curiosity about these exotic practices could only speculate or rely on the late eighteenth-century Shamanic Code.

[77] During his fieldwork among the Tungusic peoples of "Manchuria" from 1912 to 1918, Russian anthropologist S. M. Shirokogoroff (1887–1939) found enough surviving practices to develop an influential theory of shamanism.

[87] As he also discovered, the Manchus venerated many Buddhist deities, so much that he hypothesized that northeast Asian shamanism was an outgrowth of Buddhism.

Equipped with specific ritual implements, the shaman enters into a trance to gain control of harmful spirits who cause illness or misfortune to a clan or a tribe.