Shamanism

[3][4] The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world for the purpose of healing, divination, or to aid human beings in some other way.

[14] It was brought to Western Europe twenty years later by the Dutch statesman Nicolaes Witsen, who reported his stay and journeys among the Tungusic- and Samoyedic-speaking Indigenous peoples of Siberia in his book Noord en Oost Tataryen (1692).

[16] Anthropologist and archeologist Silvia Tomaskova argued that by the mid-1600s, many Europeans applied the Arabic term shaitan (meaning "devil") to the non-Christian practices and beliefs of Indigenous peoples beyond the Ural Mountains.

[17] She suggests that shaman may have entered the various Tungus dialects as a corruption of this term, and then been told to Christian missionaries, explorers, soldiers and colonial administrators with whom the people had increasing contact for centuries.

The English historian Ronald Hutton noted that by the dawn of the 21st century, there were four separate definitions of the term which appeared to be in use: According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a shaman (/ˈʃɑːmən/ SHAH-mən, /ˈʃæmən/ SHAM-ən or /ˈʃeɪmən/ SHAY-mən)[21] is someone who is regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.

According to Juha Janhunen, "the word is attested in all of the Tungusic idioms" such as Negidal, Lamut, Udehe/Orochi, Nanai, Ilcha, Orok, Manchu and Ulcha, and "nothing seems to contradict the assumption that the meaning 'shaman' also derives from Proto-Tungusic" and may have roots that extend back in time at least two millennia.

The term "shamanism" was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic- and Samoyedic-speaking peoples.

Kehoe is highly critical of Mircea Eliade's work on shamanism as an invention synthesized from various sources unsupported by more direct research.

By Western scholars, the term "shamanism" is used to refer to a variety of different cultures and practices around the world, which can vary dramatically and may not be accurately represented by a single concept.

Billy-Ray Belcourt, an author and award-winning scholar from the Driftpile Cree Nation in Canada, argues that using language with the intention of simplifying culture that is diverse, such as Shamanism, as it is prevalent in communities around the world and is made up of many complex components, works to conceal the complexities of the social and political violence that Indigenous communities have experienced at the hands of settlers.

He believes that this places more stress on the local variations[9] and emphasizes that shamanism is not a religion of sacred dogmas, but linked to the everyday life in a practical way.

[36] Historically, it is often associated with Indigenous and tribal societies, and involves belief that shamans, with a connection to the otherworld, have the power to heal the sick, communicate with spirits, and escort souls of the dead to the afterlife.

In many places shamans learn directly from the plants, harnessing their effects and healing properties, after obtaining permission from the indwelling or patron spirits.

[56] Sound mimesis in various cultures may serve other functions not necessarily related to shamanism: practical goals such as luring game in the hunt;[57] or entertainment (Inuit throat singing).

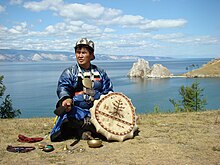

Shamans perform a variety of functions depending upon their respective cultures;[67] healing,[47][68] leading a sacrifice,[69] preserving traditions by storytelling and songs,[70] fortune-telling,[71] and acting as a psychopomp ("guide of souls").

Due to the popularity of ayahuasca tourism in South America, there are practitioners in areas frequented by backpackers who make a living from leading ceremonies.

In a culture that disapproved of female economic autonomy, the practice of shamanism allowed women to advance themselves financially and independently, in a way that had not been possible for them before.

[88][89] According to Winkelman, shamanism develops reliably in human societies because it provides valuable benefits to the practitioner, their group, and individual clients.

In particular, the trance states induced by dancing, hallucinogens, and other triggers are hypothesized to have an "integrative" effect on cognition, allowing communication among mental systems that specialize in theory of mind, social intelligence, and natural history.

[90] With this cognitive integration, the shaman can better predict the movement of animals, resolve group conflicts, plan migrations, and provide other useful services.

[3][91][92] According to Singh, shamanism is a cultural technology that adapts to (or hacks) our psychological biases to convince us that a specialist can influence important but uncontrollable outcomes.

[93] Citing work on the psychology of magic and superstition, Singh argues that humans search for ways of influencing uncertain events, such as healing illness, controlling rain, or attracting animals.

As specialists compete to help their clients control these outcomes, they drive the evolution of psychologically compelling magic, producing traditions adapted to people's cognitive biases.

[96] Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff relates these concepts to developments in the ways that modern science (systems theory, ecology, new approaches in anthropology and archeology) treats causality in a less linear fashion.

Among her unusual grave goods were 50 complete tortoise shells, a human foot, and certain body parts from animals such as a cow tail and eagle wings.

[9] According to this view, the shaman uses (and the audience understands) multiple codes, expressing meanings in many ways: verbally, musically, artistically, and in dance.

Joralemon emphasizes that in both traditional and modern medical practices, disease is not merely a biological fact but a social phenomenon, shaped by the cultural and societal contexts in which it occurs .

A subsequent text laments that shamans of older times were stronger, possessing capabilities like omnividence,[129] fortune-telling even for decades in the future, moving as fast as a bullet.

However, according to Richard L. Allen, research and policy analyst for the Cherokee Nation, they are regularly overwhelmed with inquiries by and about fraudulent shamans, (aka "plastic medicine people").

[141] He adds, "One may assume that anyone claiming to be a Cherokee 'shaman, spiritual healer, or pipe-carrier', is equivalent to a modern day medicine show and snake-oil vendor.