Anito

[4]worshiped as a protecting household deity[5][6].Anito (a term predominantly used in Northern Luzon) is also sometimes known as diwata in certain ethnic groups (especially among Visayans).

Cognates in other Austronesian cultures include the Micronesian aniti, Malaysian and Indonesian hantu or antu, Nage nitu, and Polynesian atua and aitu.

As well as Tao anito, Taivoan alid, Seediq and Atayal utux, Bunun hanitu or hanidu, and Tsou hicu among Taiwanese aborigines.

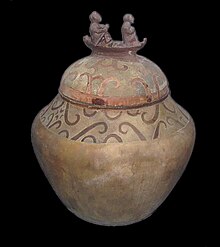

Pre-colonial Filipinos believed that upon death, the "free" soul (Visayan: kalag; Tagalog: kaluluwa)[note 1] of a person travels to a spirit world, usually by voyaging across an ocean on a boat (a bangka or baloto).

Vengeful spirits of the dead can manifest as apparitions or ghosts (mantiw)[note 4] and cause harm to living people.

[1] Ancestor spirits are also known as kalading among the Igorot;[29] tonong among the Maguindanao and Maranao;[30] umboh among the Sama-Bajau;[31] nunò or umalagad among Tagalogs and Visayans; nonò among Bicolanos;[32] umagad or umayad among the Manobo;[33] and tiladmanin among the Tagbanwa.

[note 7] They are also known as dewatu, divata, duwata, ruwata, dewa, dwata, diya, etc., in various Philippine languages (including Tagalog diwa, "spirit" or "essence"); all of which are derived from Sanskrit devata (देवता) or devá (देव), meaning "deity".

These names are the result of syncretization with Hindu-Buddhist beliefs due to the indirect cultural exchange (via Srivijaya and Majapahit) between the Philippines and South Asia.

In some ethnic groups like the B'laan, Cuyonon Visayans, and the Tagalog, Diwata refers to the supreme being in their pantheon,[note 8] in which case there are different terms for non-human spirits.

They "own" places and concepts like agricultural fields, forests, cliffs, seas, winds, lightning, or realms in the spirit world.

[33] The last is a class of malevolent spirits or demons, as well as supernatural beings, generally collectively known as aswang, yawa, or mangalos (also mangalok, mangangalek, or magalos) among Tagalogs and Visayans.

They can also take over a body through spirit possession (Visayan: hola, hulak, tagdug, or saob; Tagalog: sanib), an ability essential for the séances in pag-anito.

They are believed to be capable of shapeshifting (baliw or baylo), becoming invisible, or creating visions or illusions (anino or landung, lit.

They can also deliberately play tricks on mortals, like seducing or abducting beautiful men and women into the spirit world.

[43] To avoid inadvertently angering a diwata, Filipinos perform a customary pasintabi sa nuno ("respectfully apologizing or asking permission from ancestors for passing").

People born with congenital disorders (like albinism or syndactyly) or display unusual beauty or behavior are commonly believed by local superstition to be the children of diwata who seduced (or sometimes raped) their mothers.

[45][46] During the Spanish period, diwata were syncretized with elves and fairies in European mythology and folklore, and were given names like duende (goblin or dwarf), encantador or encanto ("spell [caster]"), hechicero ("sorcerer"), sirena ("mermaid"), or maligno ("evil [spirit]").

These were known as taotao ("little human", also taotaohan, latawo, tinatao, or tatao),[note 15] bata-bata ("little child"), ladaw ("image" or "likeness"; also laraw, ladawang, lagdong, or larawan), or likha ("creation"; also likhak) in most of the Philippines.

[55][56] In very rare cases, diwata can be depicted as taotao in anthropomorphic form, as chimeras or legendary creatures, or as animals.

They offer the idol some of the food which they are eating, and call upon him in their tongue, praying to him for the health of the sick man for whom the feast is held.

This manganito, or drunken revel, to give it a better name, usually lasts seven or eight days; and when it is finished they take the idols and put them in the corners of the house, and keep them there without showing them any reverence.Regardless, very old taotao handed down through generations are prized as family heirlooms.

[1][4][51][52] When Spanish missionaries arrived in the Philippines, the word "anito" came to be associated with these physical representations of spirits that featured prominently in pag-anito rituals.

[1][4][14][65][66] Some animals like crocodiles, snakes, monitor lizards, tokay geckos, and various birds were also venerated as servants or manifestations of diwata, or as powerful spirits themselves.

These include legendary creatures like the dragon or serpent Bakunawa, the giant bird Minokawa of the Bagobo, and the colorful Sarimanok of the Maranao.

When spoken of, these spirit creatures are marked with a prefix, reconstructed as proto-Austronesian *qali- or *kali-,[note 21] which still survive fossilized in modern languages in Austronesian cultures, though the beliefs may have long been forgotten.

However, major pag-anito rituals required the services of the community shaman (Visayan babaylan or baylan; Tagalog katalonan or manganito).

These depended on what spirit was being summoned, but offerings are usually a small portion of the harvests, cooked food, wine, gold ornaments, and betel nut.

[33] There is no record of human sacrifices being offered to anito during the Spanish period of the Philippines,[1][51][44] except among the Bagobo people in southern Mindanao where it was prevalent until the early 20th century.

The most common pag-anito were entreaties for bountiful harvests, cures for illnesses, victory in battle, prayers for the dead, or blessings.

[4][note 26] Historical accounts of anito in Spanish records include the following: The modern Filipino understanding of diwata encompasses meanings such as muse, fairy, nymph, dryad, or even deity (god or goddess).