Shanghai International Settlement

In 1854, the three countries created the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC) to serve all their interests, but, in 1862, the French concession dropped out of the arrangement.

In early 1943, new treaties signed formally ended the extraterritorial privileges of Americans and Britons, although its terms were not met until the recovery of Shanghai following Japan's 1945 surrender.

Later that year Gong Muiju and Balfour concluded an agreement called the Land Regulations (Shanghai zudi zhangcheng), which set forth the institutional basis for the British settlement.

[5] Towards the end of the 19th century, Shanghai Russians also arrived, with Russia's construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway and acquisition of Harbin and Port Arthur.

[6] On 11 July 1854 a committee of Western businessmen met and held the first annual meeting of the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC, formally the Council for the Foreign Settlement North of the Yang-king-pang), ignoring protests of consular officials, and laid down the Land Regulations which established the principles of self-government.

The aims of this first Council were simply to assist in the formation of roads, refuse collection, and taxation across the disparate Concessions.

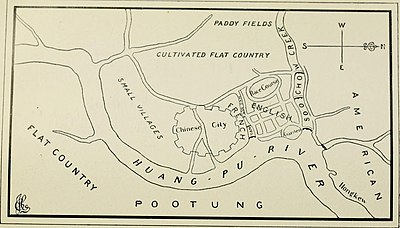

The French concession remained independent and the Chinese retained control over the original walled city and the area surrounding the foreign enclaves.

The British Consul was the de jure authority in the Settlement, but he had no actual power unless the ratepayers (who voted for the council) agreed.

Until the late-1920s, therefore, the SMC and its subsidiaries, including the police, power station, and public works, were British dominated (though not controlled, since Britain itself had no authority over the council).

Some of the Settlement's actions during this period, such as the May 30th Movement, in which Chinese demonstrators were shot by members of the Shanghai Municipal Police (leading to anti-Western protests), did embarrass and threaten the British Empire's position in China.

[10] The International Settlement was wholly foreign-controlled, with staff of all nationalities, including British, Americans, Danes, Dutch, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italians and Germans.

Britain, pre-occupied with World War I, did not press the issue and the extra-settlement roads area retained the "quasi-concession" status until the demise of the concession.

Parts of the northern extra-settlement roads area was allocated to Japan for defence purposes in 1927, which the Japanese used as a base for military operations during the 1932 January 28th Incident and the 1937 Battle of Shanghai.

After that battle, Japan took full control over the northern extra-settlement roads area and expelled International Settlement police.

Control of police, sanitation, roads, and other problems of local administration are granted to the Municipal Council simply because that body happens to be the one best equipped to deal with these matters in an area where the large majority of foreigners dwell.

However, Japan rapidly developed into a modern nation, and by the turn of the 20th century the Japanese had successfully negotiated with all powers to abrogate all unequal treaties with it.

Japan stood alongside the European powers as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance during the infamous fifty-five-day siege of the foreign embassy compound in Peking.

In 1915, during the First World War, Japan overtook Britain as the country with the largest number of foreign residents in Shanghai.

[15]: 299 Anglo-American influence effectively ended after 8 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Army entered and occupied the British and American controlled parts of the city in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

European residents of the International Settlement were forced to wear armbands to differentiate them, were evicted from their homes, and—just like Chinese citizens—were liable to maltreatment.

The Japanese sent European and American citizens to be interned at the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Center, a work camp on what was then the outskirts of Shanghai.

[17] Shanghai was notable for a long period as the only place in the world that unconditionally offered refuge for Jews escaping from the Nazis.

After the war and the liberation of the city from the Japanese, a Liquidation Commission fitfully met to discuss the remaining details of the handover.

By the end of 1945, most Westerners not actively involved in the Chinese Civil War (such as intelligence agents, soldiers, journalists, etc.)

With the defeat of the Kuomintang in 1949, the city was occupied by the Communist People's Liberation Army and came under the control of the mayor of Shanghai.

[21] Furthermore, the Chinese government adamantly refused to grant treaty power status to any of the new nations born in the wake of WWI, such as Austria and Hungary (formerly Austria-Hungary), Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, the Baltic states, or Finland.

Despite the complications arising from a mixture of Chinese and Spanish coinages, there was one overwhelming unifying factor binding all the systems in use: silver.

When China began producing official Republican yuan coins in 1934, they were minted in Shanghai and shipped to Nanking for distribution.

Starting in 1919 the 16 current regular US stamps were overprinted for use in Shanghai with the city's name, "China", and amounts double their printed face values.

International merchants brought with them amateur musical talent that manifested in the creation of the Shanghai Philharmonic Society in 1868.