Shapeshifting

Popular shapeshifting creatures in folklore are werewolves and vampires (mostly of European, Canadian, and Native American/early American origin), ichchhadhari naag (shape-shifting cobra) of India, shapeshifting fox spirits of East Asia such as the huli jing of China, the obake of Japan, the Navajo skin-walkers, and gods, goddesses and demons and demonesses such as the Norse Loki or the Greek Proteus.

While the Greek gods could use transformation punitively – such as Medusa, who turned to a monster for having sexual intercourse (raped in Ovid's version) with Poseidon in Athena's temple – even more frequently, the tales using it are of amorous adventure.

Desperate, she sat on a rock with no food or water for nine days looking at him as he crossed the skies, until she was transformed into a purple, sun-gazing flower, the heliotropium.

Eos, the goddess of the dawn, secured immortality for her lover the Trojan prince Tithonus, but not eternal youth, so he aged without dying as he shriveled and grew more and more helpless.

Tales abound about the selkie, a seal that can remove its skin to make contact in human guise with people for only a short amount of time before it must return to the sea.

[4] Other tales include kelpies who emerge from lochs and rivers in the disguise of a horse or woman to ensnare and kill weary travelers.

The most dramatic example of shapeshifting in Irish myth is that of Tuan mac Cairill, the only survivor of Partholón's settlement of Ireland.

In his centuries-long life, he became successively a stag, a wild boar, a hawk, and finally a salmon before being eaten and (as in the Wooing of Étaín) reborn as a human.

Sadhbh, the wife of the famous hero Fionn mac Cumhaill, was changed into a deer by the druid Fer Doirich when she spurned his amorous interests.

When one, Sigmund, survived, he and his nephew and son Sinfjötli killed men wearing wolfskins; when they donned the skins themselves, they were cursed to become werewolves.

Alberich, his counterpart in Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, using the Tarnhelm, takes on many forms, including a giant serpent and a toad, in a failed attempt to impress or intimidate Loki and Odin/Wotan.

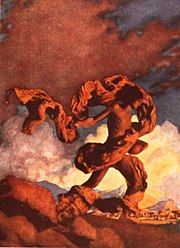

Fafnir was originally a dwarf, a giant, or even a human, depending on the exact myth, but in all variants, he transformed into a dragon—a symbol of greed—while guarding his ill-gotten hoard.

In Scandinavia, there existed, for example, the famous race of she-werewolves known by the name of Maras, women who took on the appearance of huge half-human and half-wolf monsters that stalked the night in search of human or animal prey.

If a woman gives birth at midnight and stretches the membrane that envelopes the child when it is brought forth, between four sticks and creeps through it, naked, she will bear children without pain; but all the boys will be shamans, and all the girls Maras.

In the Finnish epic poem Kalevala of ancient folklore, Louhi, Mistress of the North, attacks Väinämöinen in the form of a giant eagle with her troops on her back as she tries to steal Sampo.

In Armenian mythology, shapeshifters include the Nhang, a serpentine river monster that can transform itself into a woman or seal, and will drown humans and then drink their blood; or the beneficial Shahapet, a guardian spirit that can appear either as a man or a snake.

Tatar folklore includes Yuxa, a hundred-year-old snake that can transform itself into a beautiful young woman, and seeks to marry men to have children.

The most common such shapeshifter is the huli jing, a fox spirit that usually appears as a beautiful young woman; most are dangerous, but some feature as the heroines of love stories.

[16] He is a trickster god who can shape shift, usually taking the form of a praying mantis but also a bull eland, a louse, a snake, and a caterpillar.

They are frequently characterized in mythology with superior musical ability, seductiveness and love of sex, resulting in illegitimate children, and attraction to parties.

Despite the fact that the Encante are said to come from a utopia full of wealth which is also without pain or death, they crave the pleasures and hardships of human societies.

[34] In the Earthsea books, Ursula K. Le Guin depicts an animal form as slowly transforming the wizard's mind, so that the dolphin, bear or other creature forgets it was human, making it impossible to change back.

This may be a just punishment, the nature of the transformation matching the crime for which it occurs; in other cases, the form is unjustly imposed by an angry and powerful person.

[36] In the Italian Campania Fables collection of Pentamerone by Gianbattista Basile, tells of a Neapolitan princess who, to escape from her father who had imprisoned her, becomes a huge she-bear.

Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf, in The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, included a version of the story with the typical elements (fisherman sees mermaids dancing on an island and steals the sealskin of one of them, preventing her from becoming a seal again, so that he could marry her) and linked it to the founding of the city of Stockholm.

The Seven Ravens are transformed when their father thinks his sons are playing instead of fetching water to christen their newborn and sickly sister, and curses them.

A similar effect is found in Child ballad 34, Kemp Owyne, where the hero can transform a dragon back into a maiden by kissing her three times.

[1] In some tales, the hero or heroine must obey a prohibition; the bride must spend a period not seeing the transformed groom in human shape (as in East of the Sun and West of the Moon), or the bridegroom must not burn the animals' skins.

In The Brown Bear of Norway, The Golden Crab, The Enchanted Snake and some variants of The Frog Princess, burning the skin is a catastrophe, putting the transformed bride or bridegroom in danger.

In The Famous Flower of Serving-Men, the heroine's murdered husband appears to the king as a white dove, lamenting her fate over his own grave.