Shays's Rebellion

Historically, scholars have argued that the four thousand rebels, called Shaysites, who protested against economic and civil rights injustices by the Massachusetts Government were led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays.

By the early 2020s, scholarship has suggested that Shays's role in the protests was significantly and strategically exaggerated by Massachusetts elites, who had a political interest in shifting blame for bad economic conditions away from themselves.

The federal government, severely limited in its prerogatives under the Articles of Confederation, found itself unable to finance troops to put down the rebellion; it was consequently put down by the Massachusetts State Militia under William Shepard, alongside a privately funded local militia led by former Continental Army officer Benjamin Lincoln.

The widely-held view had already developed that the Articles of Confederation were untenable and needed amending, with the events of the rebellion serving as further evidence for the later Constitutional Convention.

[7] Prior to the 19th century, the economy of rural New England largely consisted of subsistence agriculture, particularly in the hill towns of central and western Massachusetts.

[8] In contrast, there was a market economy in the more economically developed coastal areas of Massachusetts Bay and in the fertile Connecticut River Valley, driven by the activities of wholesale merchants dealing with Europe and the West Indies.

The great men are going to get all we have and I think it is time for us to rise and put a stop to it, and have no more courts, nor sheriffs, nor collectors nor lawyers.Veterans had received little pay during the war and faced added difficulty collecting payments owed to them from the State or the Congress of the Confederation.

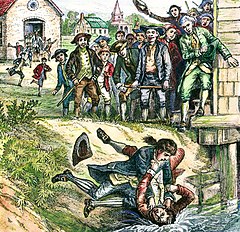

[17] One early protest against the government was led by Job Shattuck of Groton, Massachusetts, in 1782, who organized residents to physically prevent tax collectors from doing their work.

[18] A second, larger-scale protest took place in Uxbridge, Massachusetts on the Rhode Island border on February 3, 1783, when a mob seized property that had been confiscated by a constable and returned it to its owners.

[26][28] The court was then shut down in Worcester by similar action on September 5, but the county militia refused to turn out, as it was composed mainly of men sympathetic to the protestors.

[30] Matters were resolved without violence in Rhode Island because the "country party" gained control of the legislature in 1786 and enacted measures forcing its merchants to trade debt instruments for devalued currency.

[31] Daniel Shays had participated in the Northampton action and began to take a more active role in the uprising in November, though he firmly denied that he was one of its leaders.

[32] They were anticipated by William Shepard, the local militia commander, who began gathering militiamen the Saturday before the court was to sit, and he had 300 men protecting the Springfield courthouse by opening time.

Shays and Day were able to recruit a similar number but chose only to demonstrate, exercising their troops outside of Shepard's lines rather than attempting to seize the building.

Adams helped draw up a Riot Act and a resolution suspending habeas corpus so the authorities could legally keep people in jail without trial.

"The seeds of war are now sown", wrote one correspondent in Shrewsbury,[38] and by mid-January rebel leaders spoke of smashing the "tyrannical government of Massachusetts".

[39] The federal government had been unable to recruit soldiers for the army because of a lack of funding, so Massachusetts leaders decided to act independently.

[56] Most of Lincoln's army melted away in late February as enlistments expired, and he commanded only 30 men at a base in Pittsfield by the end of the month.

[57] In the meantime, around 120 rebels had regrouped in New Lebanon, New York, and they crossed the border on February 27, marching first on Stockbridge, a major market town in the southwestern corner of the state.

Several hundred participants were eventually indicted on charges relating to the rebellion, but most of these were pardoned under a general amnesty that excluded only a few ringleaders.

Vermonters responded favorably to the overture by publicly pushing Eli Parsons and Luke Day out of the state (but quietly continuing to support others).

"[67] In contrast, George Washington had been calling for constitutional reform for many years, and he wrote in a letter dated October 31, 1786, to Henry Lee, "You talk, my good sir, of employing influence to appease the present tumults in Massachusetts.

[73] Henry Knox observed that the uprising in Massachusetts clearly influenced local leaders who had previously opposed a strong federal government.

Historian David Szatmary writes that the timing of the rebellion "convinced the elites of sovereign states that the proposed gathering at Philadelphia must take place".

[76] Delegate Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut argued that because the people could not be trusted (as exemplified by Shays's Rebellion), the members of the federal House of Representatives should be chosen by state legislatures, not by popular vote.

Massachusetts Federalists, including Henry Knox, were active in courting swing votes in the debates leading up to the state's ratifying convention in 1788.

Robert Feer notes that major Federalist pamphleteers rarely mentioned it and that some anti-Federalists used the fact that Massachusetts survived the rebellion as evidence that a new constitution was unnecessary.

[82] Leonard Richards counters that publications like the Pennsylvania Gazette explicitly tied anti-Federalist opinion to the rebel cause, calling opponents of the new constitution "Shaysites" and the Federalists "Washingtonians".

[84] Richards records Henry Jackson's observation that opposition to ratification in Massachusetts was motivated by "that cursed spirit of insurgency", but that broader opposition in other states originated in other constitutional concerns expressed by Elbridge Gerry, who published a widely distributed pamphlet outlining his concerns about the vagueness of some of the powers granted in the constitution and its lack of a Bill of Rights.

[87] In the town of Petersham, Massachusetts, a memorial was erected in 1927 by the New England Society of Brooklyn, New York, in commemoration of General Benjamin Lincoln's rout of the Shaysite forces there on the morning of February 4.