Ship stability

However, the advent of calculus-based methods of determining stability, particularly Pierre Bouguer's introduction of the concept of the metacenter in the 1740s ship model basin, allow much more complex analysis.

Ships were often copied from one generation to the next with only minor changes; by replicating stable designs, serious problems were usually avoided.

Transverse bulkheads, while expensive, increase the likelihood of ship survival in the event of hull damage, by limiting flooding to the breached compartments they separate from undamaged ones.

Longitudinal bulkheads have a similar purpose, but damaged stability effects must be taken into account to eliminate excessive heeling.

Outriggers may be employed on vessels to reduce rolling, either by the force required to submerge buoyant floats or by hydrodynamic foils.

Referred to as zero-speed, or Stabilization at Rest, these systems work by moving specially designed fins with sufficient acceleration and impulse timing to create effective roll-cancelling energy.

While it proved successful in drastically reducing roll in the westbound trips, the system had to be disconnected on the eastbound leg for safety reasons.

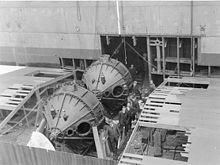

[2] Gyro stabilizers consist of a spinning flywheel and gyroscopic precession that imposes boat-righting torque on the hull structure.

The higher the angular momentum, the greater the resisting force of the gyro to external torque (in this case more ability to cancel boat roll).

Angular momentum is the measure of effectiveness for a gyro stabilizer, analogous to horsepower ratings on a diesel engine or kilowatts on a generator.

In specifications for gyro stabilizers, the total angular momentum (moment of inertia multiplied by spin speed) is the key quantity.

In modern designs, the output axis torque can be used to control the angle of the stabilizer fins (see above) to counteract the roll of the boat so that only a small gyroscope is needed.

The idea for gyro controlling a ship's fin stabilizers was first proposed in 1932 by a General Electric scientist, Dr Alexanderson.

He proposed a gyro to control the current to the electric motors on the stabilizer fins, with the actuating instructions being generated by thyratron vacuum tubes.

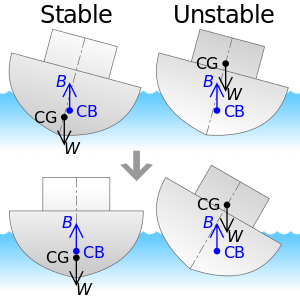

A line drawn from the center of buoyancy in a slightly heeled condition vertically will intersect the centerline at a point called the metacenter.

Water accumulating in the hull usually drains to the bilges, lowering the center of gravity and actually increasing the metacentric height.

However, once the ship is inclined to any degree (a wave strikes it for example), the fluid in the bilge moves to the lower side.

If these contents are lighter than seawater, (light oil for example) then buoyancy is lost and the section lowers slightly in the water accordingly.

In addition, United States Coast Guard rules apply to vessels operating in U.S. ports and in U.S. waters.

Because different countries may have different requirements for the minimum metacentric height, most ships are now fitted with stability computers that calculate this distance on the fly based on the cargo or crew loading.