Shockley–Queisser limit

The most popular solar cell material, silicon, has a less favorable band gap of 1.1 eV, resulting in a maximum efficiency of about 32%.

For a "blackbody" at normal temperatures, a very small part of this radiation (the number per unit time and per unit area given by Qc, "c" for "cell") is photons having energy greater than the band gap (wavelength less than about 1.1 microns for silicon), and part of these photons (Shockley and Queisser use the factor tc) are generated by recombination of electrons and holes, which decreases the amount of current that could be generated otherwise.

This is a very small effect, but Shockley and Queisser assume that the total rate of recombination (see below) when the voltage across the cell is zero (short circuit or no light) is proportional to the blackbody radiation Qc.

However, the reverse process must also be possible, according to the principle of detailed balance: an electron and a hole can meet and recombine, emitting a photon.

Thus the rate of recombination, in this model, is proportional to exp(V/Vc) times the blackbody radiation above the band-gap energy: (This is actually an approximation, correct so long as the cell is thick enough to act as a black body, to the more accurate expression[7][8] The difference in maximum theoretical efficiency however is negligibly small, except for tiny bandgaps below 200meV.

is the number of photons above the band-gap energy falling on the cell per unit area, and ts is the fraction of these that generate an electron-hole pair.

[10] This accounts for about 33% of the incident sunlight, meaning that, for silicon, from spectrum losses alone there is a theoretical conversion efficiency limit of about 48%, ignoring all other factors.

According to the authors, this ratio is well approximated by ln(fQs/Qc), where f is the combination of factors fsfωts/(2tc), in which fω is the solid angle of the sun divided by π.

Shockley and Queisser's work considered the most basic physics only; there are a number of other factors that further reduce the theoretical power.

Materials with higher electron (or hole) mobility can improve on silicon's performance; gallium arsenide (GaAs) cells gain about 5% in real-world examples due to this effect alone.

Normal silicon cells quickly saturate, while GaAs continue to improve at concentrations as high as 1500 times.

However, radiative recombination—when an electron and hole recombine to create a photon that exits the cell into the air—is inevitable, because it is the time-reversed process of light absorption.

[11] The frequency dependence of the absorption and effectively the reflectance of materials can be taken into account when calculating the solar cell efficiency.

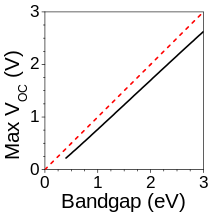

[12][13] According to Shockley-Quiesser limit, solar cell efficiency of semiconductors depend on the band gap of the material.

In the Shockley-Quiesser limit, 100% light absorption is assumed above the band gap of the material in order to find highest possible efficiency of a solar cell in case reflectance is reduced to zero for example by using an anti-reflecting coating.

However, the problem with this assumption is that absorbance below the band gap of the material at finite temperatures is neglected which can effect the efficiency.

With the inclusion of the absorption below the band gap, the lower limit of the short-circuit current integral is changed from band gap to zero and therefore the equation is defined as; where Jsc is the short-circuit current, A is the thickness dependent absorbance of the material, Jph is the AM1.5 solar energy flux, and ω is the frequency of light.

In the most common design, a high-bandgap solar cell sits on top, absorbing high-energy, shorter-wavelength light, and transmitting the rest.

[5] The majority of tandem cells that have been produced to date use three layers, tuned to blue (on top), yellow (middle) and red (bottom).

They also can be used in concentrated photovoltaic applications (see below), where a relatively small solar cell can serve a large area.

Tandem cells are not restricted to high-performance applications; they are also used to make moderate-efficiency photovoltaics out of cheap but low-efficiency materials.

If, however, the intense light heats up the cell, which often occurs in practice, the theoretical efficiency limit may go down all things considered.

In practice, the choice of whether or not to use light concentration is based primarily on other factors besides the small change in solar cell efficiency.

[22] The upconversion efficiency can be improved by controlling the optical density of states of the absorber[23] and also by tuning the angularly-selective emission characteristics.

[24] A hybrid thermophotovoltaic platform exploiting thermal upconversion was theoretically predicted to demonstrate maximum conversion efficiency of 73% under illumination by non-concentrated sunlight.

A detailed analysis of non-ideal hybrid platforms that allows for up to 15% of absorption/re-emission losses yielded limiting efficiency value of 45% for Si PV cells.

It should be no surprise that there has been a considerable amount of research into ways to capture the energy of the carriers before they can lose it in the crystal structure.

Quantum dots have been extensively investigated for this effect, and they have been shown to work for solar-relevant wavelengths in prototype solar cells.

In particular, to exceed the Shockley–Queisser limit, it is necessary for the fluorescent material to convert a single high-energy photon into several lower-energy ones (quantum efficiency > 1).

For a converter with a bandgap of 0.92 eV, efficiency is limited to 54% with a single-junction cell, and 85% for concentrated light shining on ideal components with no optical losses and only radiative recombination.