Chinese calligraphy

This type of expression has been widely practiced in China and has been generally held in high esteem across East Asia.

[1] Calligraphy is considered one of the four most-sought skills and hobbies of ancient Chinese literati, along with playing stringed musical instruments, the board game "Go", and painting.

Chinese calligraphy and ink and wash painting are closely related: they are accomplished using similar tools and techniques, and have a long history of shared artistry.

Distinguishing features of Chinese painting and calligraphy include an emphasis on motion charged with dynamic life.

According to Stanley-Baker, "Calligraphy is sheer life experienced through energy in motion that is registered as traces on silk or paper, with time and rhythm in shifting space its main ingredients.

"[2] Calligraphy has also led to the development of many forms of art in China, including seal carving, ornate paperweights, and inkstones.

The first appearance of what we recognize unequivocally to refer as "oracle bone inscriptions" comes in the form of inscribed ox scapulae and turtle plastrons from sites near modern Anyang (安陽) on the northern border of Henan province.

In 2003, at the site of Xiaoshuangqiao, about 20 km south-east of the ancient Zhengzhou Shang City, ceramic inscriptions dating to 1435–1412 BC have been found by archaeologists.

[20] The ceramic ritual vessel vats that bear these cinnabar inscriptions were all unearthed within the palace area of this site.

During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved (Keightley, 1978).

The lìshū style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, were also authorised under Qin Shi Huang.

[24] reached its peak in the Tang dynasty, when famous calligraphers like Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan produced most of the fine works in kaishu.

Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926 CE – 933 AD), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in kaishu.

The head of the brush is typically made from animal hair, such as weasel, rabbit, deer, goat, pig, tiger, wolf, etc.

It is made from the Tatar wingceltis (Pteroceltis tatarianovii), as well as other materials including rice, the paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), bamboo, hemp, etc.

In Japan, washi is made from the kozo (paper mulberry), ganpi (Wikstroemia sikokiana), and mitsumata (Edgeworthia papyrifera), as well as other materials such as bamboo, rice, and wheat.

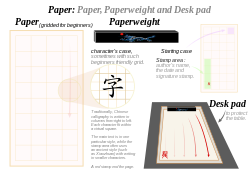

Paperweights come in several types: some are oblong wooden blocks carved with calligraphic or pictorial designs; others are essentially small sculptures of people or animals.

Some are printed with grids on both sides, so that when it is placed under the translucent paper, it can be used as a guide to ensure correct placement and size of characters.

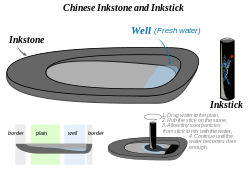

Ink is made from lampblack (soot) and binders, and comes in inksticks which must be rubbed with water on an inkstone until the right consistency is achieved.

Chinese inkstones are highly prized as art objects and an extensive bibliography is dedicated to their history and appreciation, especially in China.

The shape, size, stretch, and type of hair in the brush, the color and density of the ink, as well as the absorptive speed and surface texture of the paper are the main physical parameters influencing the final result.

Eventually, the speed, acceleration and deceleration of the writer's moves and turns, and the stroke order give "spirit" to the characters by influencing greatly their final shape.

The more practice a calligrapher has, his or her technique will transfer from youyi (intentionally making a piece of work) to wuyi (creating art with unintentional moves).

[27] Traditionally, the bulk of the study of calligraphy is composed of copying strictly exemplary works from the apprentice's master or from reputed calligraphers, thus learning them by rote.

A beginning student may practice writing the character 永 (Chinese: yǒng, eternal) for its abundance of different kinds of strokes and difficulty in construction.

In contemporary times, debate emerged on the limits of this copyist tradition within the modern art scenes, where innovation is the rule, while changing lifestyles, tools, and colors are also influencing new waves of masters.

[30] In contemporary China, a small but significant number of practitioners have made calligraphy their profession, and provincial and national professional societies exist, membership in which conferring considerable prestige.

As with other artwork, the economic value of calligraphy has increased in recent years as the newly rich in China search for safe investments for their wealth.

[32] While appreciating calligraphy depends on individual preferences, there are established traditional rules and those who repeatedly violate them are not considered legitimate calligraphers.

[35] In the case of Vietnamese calligraphy, the same styles and techniques have evolved to apply to Chữ Nôm and Latin script.