Space Shuttle Columbia

In 1992, NASA modified Columbia to be able to fly some of the longest missions in the Shuttle Program history using the Extended Duration Orbiter pallet.

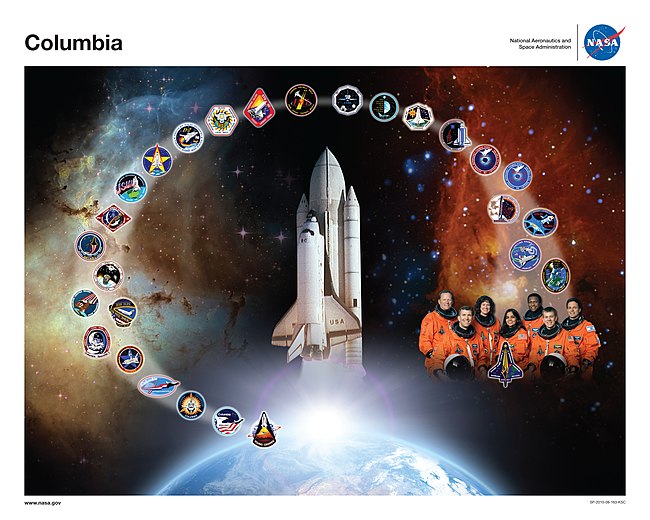

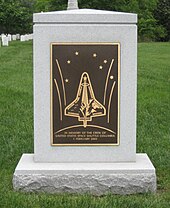

At the end of its final flight in February 2003, Columbia disintegrated upon reentry, killing the seven-member crew of STS-107 and destroying most of the scientific payloads aboard.

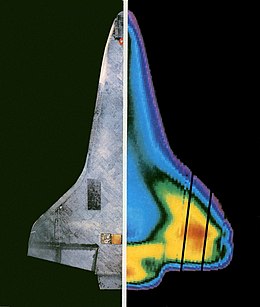

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board convened shortly afterwards concluded that damage sustained to the orbiter's left wing during the launch of STS-107 fatally compromised the vehicle's thermal protection system.

The majority of Columbia's recovered remains are stored at the Kennedy Space Center's Vehicle Assembly Building, though some pieces are on public display at the nearby Visitor Complex.

Columbia was originally scheduled to lift off in late 1979, however the launch date was delayed by problems with both the RS-25 engine and the thermal protection system (TPS).

[4] On March 19, 1981, during preparations for a ground test, workers were asphyxiated in Columbia's nitrogen-purged aft engine compartment, resulting in (variously reported) two or three fatalities.

[5][6] The first flight of Columbia (STS-1) was commanded by John Young, a veteran from the Gemini and Apollo programs who in 1972 had been the ninth person to walk on the Moon; and piloted by Robert Crippen, a rookie astronaut originally selected to fly on the military's Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL) spacecraft, but transferred to NASA after its cancellation, and served as a support crew member for the Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz missions.

In 1983, Columbia, under the command of John Young on what was his sixth spaceflight, undertook its second operational mission (STS-9), in which the Spacelab science laboratory and a six-person crew was carried, including the first non-American astronaut on a space shuttle, Ulf Merbold.

The mission's crew included Franklin Chang-Diaz, and the first sitting member of the House of Representatives to venture into space, Bill Nelson.

Prior to the accident, Columbia had been slated to be ferried to Vandenberg Air Force Base to conduct fueling tests and to perform a flight readiness firing at SLC-6 to validate the west coast launch site.

Consequently, President George W. Bush decided to retire the Shuttle orbiter fleet by 2010 in favor of the Constellation program and its crewed Orion spacecraft.

[11] The retention of the internal airlock allowed NASA to use Columbia for the STS-109 Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission, along with the Spacehab double module used on STS-107.

Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour all, until 1998, bore markings consisting of the letters "USA" above an American flag on the left-wing, and the pre-1998 NASA "worm" logotype afore the respective orbiter's name on the right-wing.

From its last refit following the conclusion of STS-93 to its destruction, Columbia bore markings identical to those of its operational sister orbiters–the NASA "meatball" insignia on the left-wing and the American flag afore the orbiter's name on the right-wing.

Though the pod's equipment was removed after initial tests, NASA decided to leave it in place, mainly to save costs, along with the agency's plans to use it for future experiments.

One unique feature that permanently stayed on Columbia from STS-1 to STS-107 was the OEX (Orbiter Experiments) box or MADS (Modular Auxiliary Data System) recorder.

On March 19, 2003, this "black box" was found slightly damaged but fully intact by the U.S. Forest Service in San Augustine County in Texas after weeks of search and recovery efforts after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

Had Columbia not been destroyed, it would have been fitted with the external airlock/docking adapter for STS-118, an International Space Station assembly mission, originally planned for November 2003.

Because of the retirement of the Space Shuttle fleet, the batteries and gyroscopes that keep the telescope pointed will eventually fail, which would result in its reentry and breakup in Earth's atmosphere.

Columbia was built according to a heavier earlier design with a reduced payload for ISS missions, so it was decided not to install a Space Station docking system.

The hole had formed when a piece of insulating foam from the external fuel tank peeled off during the launch 16 days earlier and struck the shuttle's left wing.

The resulting loss of control exposed minimally protected areas of the orbiter to full-entry heating and dynamic pressures that eventually led to vehicle break up.

[22] The nearly 84,000 pieces of collected debris of the vessel are stored in a large room on the 16th-floor of the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center.

The museum features two interactive simulator displays that emulate activities of the shuttle and orbiter, and the digital learning center and its classroom provide educational opportunities.

[28] The first part of the system, built in 2003, was dedicated to STS-107 astronaut and engineer Kalpana Chawla, who prior to joining the Space Shuttle program worked at Ames Research Center.

A refurbished Columbia features prominently in a 1999 episode of Cowboy Bebop, being used to rescue series protagonist Spike from burning up in Earth's atmosphere after his ship runs out of fuel.

After capturing the stray craft in its cargo bay, Columbia encounters trouble on its return to Earth, including a failure of the heat shielding, finally crash landing in a desert with its occupants unharmed.

[30] In response to the loss of Columbia, guitarist Steve Morse of the rock band Deep Purple wrote the instrumental "Contact Lost" which was featured as the closing track on their 2003 album Bananas.

[31] Astronaut and mission specialist engineer Kalpana Chawla, one of the victims of the accident, was a fan of Deep Purple and had exchanged e-mails with the band during the flight, making the tragedy even more personal for the group.

Johnson said "I wanted to make it more of a positive message, a salute, a celebration rather than just concentrating on a few moments of tragedy, but instead the bigger picture of these brave people's lives.