Sierra de la Plata

The legend began in the early 16th century when castaways from the Juan Díaz de Solís expedition heard indigenous stories of a mountain of silver in an inland region ruled by the so-called White King.

The outposts founded during the expeditions gradually evolved into Buenos Aires and Asunción, the lands colonized by the Spanish became Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

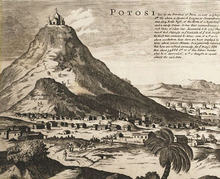

Eventually, a Spanish expedition traveling from Peru in 1545 found the Cerro Rico de Potosí in Bolivia, a massive silver deposit deep in the Andes.

After exploring the area and guessing it could be a strait connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific, Solís returned to Spain to stake his claim as conqueror and governor of the region.

[1] In 1516, he returned with the title of Captain General, but when Solís and his party landed on the eastern bank of the Río de la Plata, they were attacked and killed by Guaranís.

[1] On their way back to Europe, one of the Solís expedition's vessels shipwrecked off the coast of Santa Catarina Island in what is now Brazil, leaving eighteen men stranded.

Garcia left Santa Catarina along with other castaways and a large indigenous party to search for the Sierra de la Plata, crossing most of South America before reaching the Andean altiplano.

During a stopover in Pernambuco in northern Brazil, he first heard the story about a land rich in precious metals far inland, which could be reached via an enormous estuary further south.

The legend captivated Cabot, so he abandoned his mission and decided to find the Sierra de la Plata, assuming that the royal authorities would be indulgent if he found enough silver.

On Santa Catarina, the castaways Melchor Rodríguez and Enrique Morales confirmed the stories, telling Cabot about Aleixo Garcia's expedition and showing him the metals that had been brought back.

In 1527, at the confluence of the Paraná and Carcarañá Rivers, Cabot established the fort of Sancti Spiritu, the first European settlement in the Río de la Plata basin, and a future base for expeditions to the land of the White King.

In February 1529, they reached an indigenous town they called Santa Ana, where they were treated hospitably, fed well, and told rumors of other "white men" who were coming up the river behind them.

After a brief dispute, the two captains decided to join forces to find the Sierra de la Plata, with Cabot in charge of the unified fleet.

Meanwhile, Buenos Aires had overcome its famine thanks to provisions Gonzalo de Mendoza brought from Brazil, and was left under the provisional command of Captain Francisco Ruiz Galán, who ordered the first planting of corn with the goal of making the fort self-sustainable.

Meanwhile, Juan de Ayolas was further up the river Paraguay in Payagua territory, where he met one of Aleixo Garcia's former companions, who told him how difficult the journey had been, due to all the gold and silver that weighed them down.

Hearing this story, Ayolas decided to found the port of Candelaria on the spot (close to present-day Corumbá) and commissioned Domingo Martínez de Irala as provisional Lieutenant Governor until he returned from an overland expedition with 130 soldiers.

On his return trip, his party suffered losses from skirmishes with indigenous people, and before he reached the Paraguay River, he ordered his men to bury most of the treasure they carried.

In September 1543, Cabeza de Vaca led his own expedition through the forest, but sickness and clashes with his officers, mostly Irala's men, convinced him to abandon his search and return to Asunción.

Irala sent a party to speak with the governor of Peru, Pedro de la Gasca, who only ordered the expedition to go no further under pain of death, so they had no choice but to return to Asunción.

Meanwhile, the king named Juan de Sanabria as the new adelantado in the region, but he died during preparations and was replaced by his son Diego, who ended up staying in Europe even though several of his ships had already sailed.

With Buenos Aires destroyed and the Sierra de la Plata under another jurisdiction, Paraguay experienced a long period of isolation under Irala, who finally died in October 1556 at the age of 70.