Animal communication

[21] Animals rely on signals called electrolocating and echolocating; they use sensory senses in order to navigate and find prey.

Vocal communication serves many purposes, including mating rituals, warning calls, conveying location of food sources, and social learning.

Examples include frogs, hammer-headed bats, red deer, humpback whales, elephant seals, and songbirds.

Crickets and grasshoppers are well known for this, but many others use stridulation as well, including crustaceans, spiders, scorpions, wasps, ants, beetles, butterflies, moths, millipedes, and centipedes.

The structure of swim bladders and the attached sonic muscles varies greatly across bony fish families, resulting in a wide variety of sounds.

Other examples include bill clacking in birds, wing clapping in manakin courtship displays, and chest beating in gorillas.

[41] This method of communication is usually done by having a sentry stand on two feet and surveying for potential threats while the rest of the pack finds food.

[43] Minnows with the ability to perceive the presence of predators before they are close enough to be seen and then respond with adaptive behavior (such as hiding) are more likely to survive and reproduce.

[45] As has also been observed in other species, acidification and changes in pH physically disrupt these chemical cues, which has various implications for animal behavior.

It is seen primarily in aquatic animals, though some land mammals, notably the platypus and echidnas, sense electric fields that might be used for communication.

[54] Examples include: Seismic communication is the exchange of information using self-generated vibrational signals transmitted via a substrate such as the soil, water, spider webs, plant stems, or a blade of grass.

Tetrapods usually make seismic waves by drumming on the ground with a body part, a signal that is sensed by the sacculus of the receiver.

[62] The sacculus is an organ in the inner ear containing a membranous sac that is used for balance, but can also detect seismic waves in animals that use this form of communication.

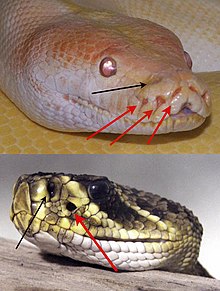

[64] It was previously thought that the pit organs evolved primarily as prey detectors, but it is now believed that they may also be used to control body temperature.

For example, a domestic dog's tail wag and posture may be used in different ways to convey many meanings as illustrated in Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872.

For example, canines such as wolves and coyotes may adopt an aggressive posture, such as growling with their teeth bared, to indicate they will fight if necessary, and rattlesnakes use their well-known rattle to warn potential predators of their venomous bite.

al., 2004), ungulates (Caro, 1995), rabbits (Holley 1993), primates (Zuberbuhler et al. 1997), rodents (Shelley and Blumstein 2005, Clark, 2005), and birds (Alvarez, 1993, Murphy, 2006, 2007).

A familiar example of quality advertisement pursuit-deterrent signal is stotting (sometimes called pronking), a pronounced combination of stiff-legged running while simultaneously jumping shown by some antelopes such as Thomson's gazelle in the presence of a predator.

Predators like cheetahs rely on surprise attacks, proven by the fact that chases are rarely successful when antelope stot.

The banner-tailed kangaroo rat produces several complex foot-drumming patterns in a number of different contexts, one of which is when it encounters a snake.

Highly elaborate behaviours have evolved for communication such as the dancing of cranes, the pattern changes of cuttlefish, and the gathering and arranging of materials by bowerbirds.

The early ethologists assumed that communication occurred for the good of the species as a whole, but this would require a process of group selection which is believed to be mathematically impossible in the evolution of sexually reproducing animals.

Sociobiologists argued that behaviours that benefited a whole group of animals might emerge as a result of selection pressures acting solely on the individual.

A gene-centered view of evolution proposes that behaviours that enabled a gene to become wider established within a population would become positively selected for, even if their effect on individuals or the species as a whole was detrimental;[83] In the case of communication, an important discussion by John Krebs and Richard Dawkins established hypotheses for the evolution of such apparently altruistic or mutualistic communications as alarm calls and courtship signals to emerge under individual selection.

The possibility of evolutionarily stable dishonest communication has been the subject of much controversy, with Amotz Zahavi in particular arguing that it cannot exist in the long term.

Sociobiologists have also been concerned with the evolution of apparently excessive signaling structures such as the peacock's tail; it is widely thought that these can only emerge as a result of sexual selection, which can create a positive feedback process that leads to the rapid exaggeration of a characteristic that confers an advantage in a competitive mate-selection situation.

[87] The researchers stated that CDS benefits for humans are cueing the child to pay attention, long-term bonding, and promoting the development of lifelong vocal learning, with parallels in these bottlenose dolphins in an example of convergent evolution.

Some of our bodily features—eyebrows, beards and moustaches, deep adult male voices, perhaps female breasts—strongly resemble adaptations to producing signals.

In object choice tasks, dogs utilize human communicative gestures such as pointing and direction of gaze in order to locate hidden food and toys.

This form of training previously has been used in schools and clinics with humans with special needs, such as children with autism, to help them develop language.