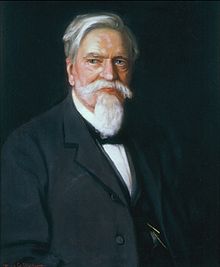

Simon Bolivar Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner (/ˈsaɪmən ˈbɒlɪvər ˈbʌknər/ SY-mən BOL-i-vər BUK-nər; April 1, 1823 – January 8, 1914) was an American soldier, Confederate military officer, and politician.

After his release, Buckner participated in Braxton Bragg's failed invasion of Kentucky and near the end of the war became chief of staff to Edmund Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi Department.

He was the National Democratic Party's candidate for Vice President of the United States in the 1896 election, but polled just over one percent of the vote on a ticket with his running mate, ex-Union general John M. Palmer.

[8][9] He was assigned to garrison duty at Sackett's Harbor on Lake Ontario until August 28, 1845, when he returned to the Academy to serve as an assistant professor of geography, history, and ethics.

While Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott besieged Vera Cruz, Buckner's unit engaged a few thousand Mexican cavalry at a nearby town called Amazoque.

[19] Before leaving the Army, Buckner helped an old friend from West Point and the Mexican–American War, Captain Ulysses S. Grant, by covering his expenses at a New York hotel until money arrived from Ohio to pay for his passage home.

In overall command was the influential politician and military novice John B. Floyd; Buckner's peers were Gideon J. Pillow and Bushrod Johnson.

[30] Buckner's division defended the right flank of the Confederate line of entrenchments that surrounded the fort and the small town of Dover, Tennessee.

On February 14, the Confederate generals decided they could not hold the fort and planned a breakout, hoping to join with Johnston's army, now in Nashville.

At dawn the following morning, Pillow launched a strong assault against the right flank of Grant's army, pushing it back 1 to 2 miles (2 to 3 km).

Buckner, not confident of his army's chances and not on good terms with Pillow, held back his supporting attack for over two hours, which gave Grant's men time to bring up reinforcements and reform their line.

[31] Late that night the generals held a council of war in which Floyd and Pillow expressed satisfaction with the events of the day, but Buckner convinced them that they had little realistic chance to hold the fort or escape from Grant's army, which was receiving steady reinforcements.

General Floyd, concerned he would be tried for treason if captured by the North, sought Buckner's assurance that he would be given time to escape with some of his Virginia regiments before the army surrendered.

Sending his aide Colonel William Hillyer to deliver a dispatch in person, Grant's reply included his famous quotation, "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

The surrender was a humiliation for Buckner personally, but also a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men and much equipment, as well as control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.

[37] While Buckner was a Union prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston, Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis unsuccessfully sought to have him tried for treason.

The small town was important for Union forces to hold if they wanted to maintain communication with Louisville while pressing southward to Bowling Green and Nashville.

Bragg left his army and met Kirby Smith in Frankfort, where he was able to attend the inauguration of Confederate Governor Richard Hawes on October 4.

Buckner, although protesting this distraction from the military mission, attended as well and gave stirring speeches to the local crowds about the Confederacy's commitment to the state of Kentucky.

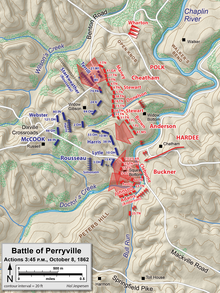

Finally, on October 8, 1862, Bragg's army—not yet concentrated with Kirby Smith's—engaged Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook's corps of Buell's army and began the Battle of Perryville.

His gallantry was for naught, however, as Perryville ended in a tactical draw that was costly for both sides, causing Bragg to withdraw and abandon his invasion of Kentucky.

Buckner's Corps fought on the Confederate left both days, the second under the "wing" command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, participating in the great breakthrough of the Union line.

Bragg held an ineffective siege against Chattanooga, but refused to take any further action as the Union forces there were reinforced by Ulysses S. Grant and reopened a tenuous supply line.

Thomas L. Connelly, historian of the Army of Tennessee, believes that Buckner was the author of the anti-Bragg letter sent by the generals to President Jefferson Davis.

Rumors began to swirl in both Union and Confederate camps that Smith and Buckner would not surrender, but would fall back to Mexico with soldiers who remained loyal to the Confederacy.

He remained in New Orleans, worked on the staff of the Daily Crescent newspaper, engaged in a business venture, and served on the board of directors of a fire insurance company, of which he became president in 1867.

[9][62] His wife and daughter joined him in the winter months of 1866 and 1867, but he sent them back to Kentucky in the summers because of the frequent outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever.

Buckner had a keen interest in politics and friends had been urging him to run for governor since 1867, even while terms of his surrender confined him to Louisiana.

[1] In this capacity, he unsuccessfully sought to extend the governor's appointment powers and levy taxes on churches, clubs, and schools that made a profit.

The ticket was endorsed by several major newspapers including the Chicago Chronicle, Louisville Courier-Journal, Detroit Free Press, Richmond Times, and New Orleans Picayune.