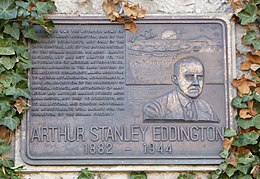

Arthur Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, OM, FRS (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician.

Eddington wrote a number of articles that announced and explained Einstein's theory of general relativity to the English-speaking world.

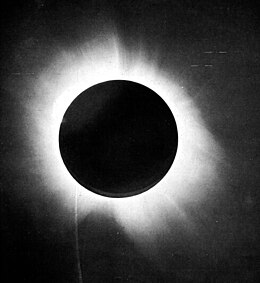

He also conducted an expedition to observe the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919 on the Island of Príncipe that provided one of the earliest confirmations of general relativity, and he became known for his popular expositions and interpretations of the theory.

The family moved to Weston-super-Mare where at first Stanley (as his mother and sister always called Eddington) was educated at home before spending three years at a preparatory school.

He began by extending Karl Schwarzschild's earlier work on radiation pressure in Emden polytropic models.

He developed his model despite knowingly lacking firm foundations for understanding opacity and energy generation in the stellar interior.

However, his results allowed for calculation of temperature, density and pressure at all points inside a star (thermodynamic anisotropy), and Eddington argued that his theory was so useful for further astrophysical investigation that it should be retained despite not being based on completely accepted physics.

James Jeans contributed the important suggestion that stellar matter would certainly be ionized, but that was the end of any collaboration between the pair, who became famous for their lively debates.

This was a particularly remarkable development since at that time fusion and thermonuclear energy, and even the fact that stars are largely composed of hydrogen (see metallicity), had not yet been discovered.

The confirmation of his estimated stellar diameters by Michelson in 1920 proved crucial in convincing astronomers unused to Eddington's intuitive, exploratory style.

Eddington's theory appeared in mature form in 1926 as The Internal Constitution of the Stars, which became an important text for training an entire generation of astrophysicists.

[7] During World War I, Eddington was secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, which meant he was the first to receive a series of letters and papers from Willem de Sitter regarding Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Eddington was fortunate in being not only one of the few astronomers with the mathematical skills to understand general relativity, but owing to his internationalist and pacifist views inspired by his Quaker religious beliefs,[5][8] one of the few at the time who was still interested in pursuing a theory developed by a German physicist.

He and Astronomer Royal Frank Watson Dyson organized two expeditions to observe a solar eclipse in 1919 to make the first empirical test of Einstein's theory: the measurement of the deflection of light by the Sun's gravitational field.

Before the appeal tribunal in June, Eddington claimed conscientious objector status, which was not recognized and would have ended his exemption in August 1918.

Eddington's personal statement at the June hearing about his objection to war based on religious grounds is on record.

Eddington made clear his willingness to serve in the Friends' Ambulance Unit, under the jurisdiction of the British Red Cross, or as a harvest labourer.

However, the tribunal's decision to grant a further twelve months' exemption from military service was on condition of Eddington continuing his astronomy work, in particular in preparation for the Príncipe expedition.

[9] This effect is noticeable only during a total solar eclipse when the sky is dark enough to see stars which are normally obscured by the Sun's brightness.

Eddington's observations published the next year[9] allegedly confirmed Einstein's theory, and were hailed at the time as evidence of general relativity over the Newtonian model.

The rejection of the results from the expedition to Brazil was due to a defect in the telescopes used which, again, was completely accepted and well understood by contemporary astronomers.

He was an early advocate of Einstein's general relativity, and an interesting anecdote well illustrates his humour and personal intellectual investment: Ludwik Silberstein, a physicist who thought of himself as an expert on relativity, approached Eddington at the Royal Society's (6 November) 1919 meeting where he had defended Einstein's relativity with his Brazil-Príncipe solar eclipse calculations with some degree of scepticism, and ruefully charged Arthur as one who claimed to be one of three men who actually understood the theory (Silberstein, of course, was including himself and Einstein as the other).

He was convinced that the mass of the proton and the charge of the electron were a "natural and complete specification for constructing a Universe" and that their values were not accidental.

Moreover, Eddington's emphasis on the values of the fundamental constants, and specifically upon dimensionless numbers derived from them, is nowadays a central concern of physics.

But no one can deny that mind is the first and most direct thing in our experience, and all else is remote inference.The idealist conclusion was not integral to his epistemology but was based on two main arguments.

[22] Ian Barbour, in his book Issues in Science and Religion (1966), p. 133, cites Eddington's The Nature of the Physical World (1928) for a text that argues the Heisenberg uncertainty principle provides a scientific basis for "the defense of the idea of human freedom" and his Science and the Unseen World (1929) for support of philosophical idealism, "the thesis that reality is basically mental".

In the scientific world (which has to fulfill functions less vague than merely existing) there is a moon which appeared on the scene before the astronomer; it reflects sunlight when no one sees it; it has mass when no one is measuring the mass; it is distant 240,000 miles from the earth when no one is surveying the distance; and it will eclipse the sun in 1999 even if the human race has succeeded in killing itself off before that date.Against Albert Einstein and others who advocated determinism, indeterminism—championed by Eddington—says that a physical object has an ontologically undetermined component that is not due to the epistemological limitations of physicists' understanding.

[23] Eddington proclaimed "It is a consequence of the advent of the quantum theory that physics is no longer pledged to a scheme of deterministic law".

[24] Eddington agreed with the tenet of logical positivism that "the meaning of a scientific statement is to be ascertained by reference to the steps which would be taken to verify it".

Eddington's books and lectures were immensely popular with the public, not only because of his clear exposition, but also for his willingness to discuss the philosophical and religious implications of the new physics.