Situated cognition

While situated cognition gained recognition in the field of educational psychology in the late twentieth century,[3] it shares many principles with older fields such as critical theory,[4][5] anthropology (Jean Lave & Etienne Wenger, 1991), philosophy (Martin Heidegger, 1968), critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 1989), and sociolinguistics theories (Bakhtin, 1981) that rejected the notion of truly objective knowledge and the principles of Kantian empiricism.

[7] More recent perspectives of situated cognition have focused on and draw from the concept of identity formation[8] as people negotiate meaning through interactions within communities of practice.

[9][10] Situated cognition perspectives have been adopted in education,[11] instructional design,[12] online communities and artificial intelligence (see Brooks, Clancey).

[19] Perception should not be considered solely as the encoding of environmental features into the perceiver's mind, but as an element of an individual's interaction with her environment (Gibson, 1977).

It is important to note that Gibson's notion of direct perception as an unmediated process of noticing, perceiving, and encoding specific attributes from the environment, has long been challenged by proponents of a more category-based model of perception.[who?]

[clarification needed] Situated cognition and ecological psychology perspectives emphasize perception and propose that memory plays a significantly diminished role in the learning process.

[24] Therefore, the agent directly perceives and interacts with the environment, determining what affordances can be picked up, based on his effectivities, and does not simply recall stored symbolic representations.

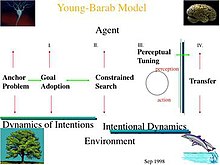

[25] Knowing emerges as individuals develop intentions[26] through goal-directed activities within cultural contexts which may in turn have larger goals and claims of truth.

The adoption of intentions relates to the direction of the agent's attention to the detection of affordances in the environment that will lead to accomplishment of desired goals.

Since knowing is rooted in action and can not be decontextualized from individual, social, and historical goals[25] teaching approaches that focus on conveying facts and rules separately from the contexts within which they are meaningful in real-life do not allow for learning that is based on the detection of invariants.

Originating from emergent literacy,[31] specialist-language lessons examines the formal and informal styles and discourses of language use in socio-cultural contexts.

[29] According to Jean Lave and Wenger (1991) legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) provides a framework to describe how individuals ('newcomers') become part of a community of learners.

To illustrate the role of LPP in situated activity, Lave and Wenger (1991) examined five apprenticeship scenarios (Yucatec midwives, Vai and Gola tailors, naval quartermasters, meat cutters, and non-drinking alcoholics involved in AA).

Their analysis of apprenticeship across five different communities of learners lead them to several conclusions about the situatedness of LPP and its relationship to successful learning.

Key to newcomers' success included: Suchman's book, Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-machine Communication (1987), provided a novel approach to the study of human-computer interaction (HCI).

Most organizational theorists would now see this debate as reflecting individual/cognitive vs. socially-situated levels of analysis (requiring a similar need for paradigmatic co-existence as Wave–particle duality).

Suchman (1993) argues that planning in the context of work-activity is similar to navigating a canoe through rapids: you know what point on the river you are aiming for, but you constantly adjust your course as you interact with rocks, swells, and currents on the way.

[7] In situated theories, the term "representation" refers to external forms in the environment that are created through social interactions to express meaning (language, art, gestures, etc.)

[35] Furthermore, transfer can only "occur when there is a confluence of an individual's goals and objectives, their acquired abilities to act, and a set of affordances for action".

[38] Additionally, research has shown that embodied facial expressions influence judgments,[39] and arm movements are related to a person's evaluation of a word or concept.

David Chalmers and Andy Clark, who developed the hugely debated model of the extended mind, explicitly rejected the externalization of consciousness.

On the other hand, others, like Riccardo Manzotti[41] or Teed Rockwell,[42] explicitly considered the possibility to situate conscious experience in the environment.

Cognitive apprenticeship includes the enculturation of students into authentic practices through activity and social interaction (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989).

The technique draws on the principles of Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and reciprocal teaching (Palincsar & Brown, 1984; 1989) in that a more knowledgeable other, i.e. a teacher, engages in a task with a more novice other, i.e. a learner, by describing their own thoughts as they work on the task, providing "just in time" scaffolding, modeling expert behaviors, and encouraging reflection.

[44] Collins, Brown, and Newman (1989) emphasized six critical features of a cognitive apprenticeship that included observation, coaching, scaffolding, modeling, fading, and reflection.

Using these critical features, expert(s) guided students on their journey to acquire the cognitive and metacognitive processes and skills necessary to handle a variety of tasks, in a range of situations[45] Reciprocal teaching, a form of cognitive apprenticeship, involves the modeling and coaching of various comprehension skills as teacher and students take turns in assuming the role of instructor.

Through authentic tasks across multiple domains, educators present situations that require students to create or adopt meaningful goals (intentions).

In terms of situated assessment, virtual worlds have the advantage of facilitating dynamic feedback that directs the perceiving/acting agent, through an avatar, to continually improve performance.

The claims and their arguments were: Anderson, Reder and Simons summarize their concerns when they say: "What is needed to improve learning and teaching is to continue to deepen our research into the circumstances that determine when narrower or broader contexts are required and when attention to narrower or broader skills are optimal for effective and efficient learning" (p. 10).

[50] Lave and Wenger recognized this in their ironic comment, "How can we purport to be working out a theoretical conception of learning without engaging in the project of abstraction [decontextualized knowledge] rejected above?"