Skew arch

[3][4] Another notable exception is an aqueduct, designed by British engineer Benjamin Outram, constructed in masonry and completed in 1798, which still carries the Ashton Canal at an angle of 45° over Store Street in Manchester.

[9][10][11] The common method they all used was to clad the timber centring (also known as falsework) with planks, known as "laggings", laid parallel with the abutments and carefully planed and levelled to approximate closely the required curve of the intrados of the arch.

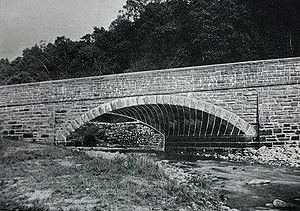

[13] An example of the latter type of construction is Denbigh Hall Bridge, built in 1837 to carry the London and Birmingham Railway across Watling Street at an acute angle of only 25°.

[6] The eminent canal engineer James Brindley never succeeding in working out a solution to the problem of constructing a strong skew arch and as a consequence all his overbridges were built at right angles to the waterway, with double bends in the roadway, where necessary, and to this day many of them cause inconvenience to their users.

[5] Though Outram's Store Street Aqueduct was constructed with this principle in mind, it was done so empirically, with the masons cutting each voussoir stone as it was required, and it was not until 1828 that details of the technique were published in a form that was useful to other engineers and stonemasons.

[24] Nicholson never pretended to have invented the skew arch but in his later work The Guide to Railway Masonry, containing a Complete Treatise on the Oblique Arch (1839), he does claim to have invented the method for producing the templates that enabled the accurate cutting of the voussoir stones used in all skew bridges built between the years 1828 and 1836, citing testimonials from the builders of major works, such as the Croft Viaduct[25] at Croft-on-Tees near Darlington.

[2][28] Secondly, it enabled him to develop an arbitrary number of concentric intermediate surfaces so as to plan the courses in multi-ring skew arch barrels, allowing them for the first time to be constructed in brick, and therefore much more economically than was previously possible.

"[2] So, a stone skew arch built to Fox's plan would have its voussoirs cut with a slight twist, in order to follow the shape of a square threaded screw.

[23] Unfortunately the three men became involved in a paper war that, following a number of earlier altercations in which the originality of his writings was questioned, left the 71-year-old Nicholson feeling bitter and unappreciated.

[30] The following year Fox, still aged only 28 and employed by Robert Stephenson as an engineer on the London and Birmingham Railway, presented his paper encapsulating these principles to the Royal Institution and from this was born the English or helicoidal method of constructing brick skew arches.

[37] Shortly before the railway opened the bridge was the subject of an ink and wash drawing dated 12 June 1837, one of a series of works by artist John Cooke Bourne illustrating the construction of the line.

[54] In 1838, Alexander James Adie,[55] son of the famous optical instrument manufacturer of the same name,[56] as resident engineer on the Bolton and Preston Railway was the first to put the theory into practice,[57] building several skew bridges to the logarithmic pattern on that route, including the semi-elliptical Grade II listed[58] bridge number 74A that carries the line over the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which was formerly known as the southern section of the Lancaster Canal with the intention of connecting it to the northern section, though this was never achieved as the necessary aqueduct over the River Ribble proved too expensive to build.

[62] Despite being known as the French method of skew arch building, it was actually introduced by English engineer William Froude whilst working under Isambard Kingdom Brunel on the Bristol and Exeter Railway, which opened in 1844.

[64] The brickwork is considerably more complex than in a helicoidal design and, in order to ensure that the courses of bricks meet the faces of the arch at right angles, many had to be cut to produce tapers.

[66] Motivated by the lack of skilled stonemasons in the 18th century United States, the design was first proposed in 1802 for a crossing of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia by British-born American architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe[67] and later championed by French civil engineer A.

[67] The Midland Railway in the United Kingdom suffered from no such shortage of skilled workers but as part of its southern extension towards its London terminus at St Pancras, it was faced with the need to cross Southdown Road in Harpenden at an extremely acute angle of approximately 25°,[71] a figure more acute than the theoretical limit of 25°40′ proposed by Buck,[35] and requiring a bridge with a skew angle of 65°, a situation not unlike that faced by the London and Birmingham railway 30 years earlier at Denbigh Hall.

This time the chosen solution was to build Southdown Road bridge as a ribbed skew arch, which opened for traffic in 1868 and was successfully widened in 1893 when the line was converted to quadruple track.

[76] Early skew arch bridges were painstakingly built from masonry blocks, each individually and expensively cut to its own unique shape, with no two edges either parallel or perpendicular.

[6][77][78] A contemporary skew bridge built to carry the Haggerleazes branch of the Stockton and Darlington Railway over the River Gaunless in County Durham proved too difficult for the original contractors, Thomas Worth and John Batie, who, after piling the foundations for the abutments and laying the lower courses of masonry, abandoned the work.

As the principles were not completely understood, the work continued to prove difficult and its imminent collapse was solemnly predicted right up until the time, a few days before the opening of the branch, the centring was removed and the crown of the arch settled by less than half an inch (13 mm).