Skin effect

Skin effect has practical consequences in the analysis and design of radio-frequency and microwave circuits, transmission lines (or waveguides), and antennas.

It is also important at mains frequencies (50–60 Hz) in AC electric power transmission and distribution systems.

Although the term skin effect is most often associated with applications involving transmission of electric currents, skin depth also describes the exponential decay of the electric and magnetic fields, as well as the density of induced currents, inside a bulk material when a plane wave impinges on it at normal incidence.

The imaginary part of the exponent indicates that the phase of the current density is delayed 1 radian for each skin depth of penetration.

One full wavelength in the conductor requires 2π skin depths, at which point the current density is attenuated to e−2π (1.87×10−3, or −54.6 dB) of its surface value.

In good conductors such as metals all of those conditions are ensured at least up to microwave frequencies, justifying this formula's validity.

However, in very poor conductors, at sufficiently high frequencies, the quantity inside the large parentheses increases.

This departure from the usual formula only applies for materials of rather low conductivity and at frequencies where the vacuum wavelength is not much larger than the skin depth itself.

For instance, bulk silicon (undoped) is a poor conductor and has a skin depth of about 40 meters at 100 kHz (λ = 3 km).

The conclusion is that in poor solid conductors, such as undoped silicon, skin effect does not need to be taken into account in most practical situations.

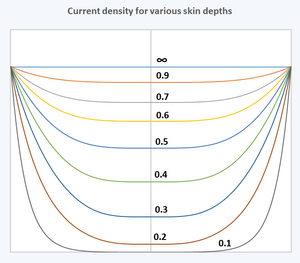

When skin depth is not small with respect to the radius of the wire, current density may be described in terms of Bessel functions.

The current density inside round wire away from the influences of other fields, as function of distance from the axis is given by:[6]: 38

This impedance is a complex quantity corresponding to a resistance (real) in series with the reactance (imaginary) due to the wire's internal self-inductance, per unit length.

It can be shown that this will have a minor effect on the self-inductance of the wire itself; see Skilling[9] or Hayt[10] for a mathematical treatment of this phenomenon.

However, the presence of a second conductor in the case of a transmission line reduces the extent of the external magnetic field (and of the total self-inductance) regardless of the wire's length, so that the inductance decrease due to skin effect can still be important.

For instance, in the case of a telephone twisted pair, below, the inductance of the conductors substantially decreases at higher frequencies where skin effect becomes important.

is not changed by the skin effect and is given by the frequently cited formula for inductance L per length D of a coaxial cable:

Although the geometry is different, a twisted pair used in telephone lines is similarly affected: at higher frequencies, the inductance decreases by more than 20% as can be seen in the following table.

Iron wire is impractical for AC power lines (except to add mechanical strength by serving as a core to a non-ferromagnetic conductor like aluminum).

At a few kilohertz, an iron welding rod would glow red hot as current flows through the greatly increased AC resistance resulting from skin effect, with relatively little power remaining for the arc itself.

[17] Conductive threads composed of carbon nanotubes[18] have been demonstrated as conductors for antennas from medium wave to microwave frequencies.

Tubular conductors are typical in electric power switchyards where the distance between supporting insulators may be several meters.

This technique is particularly used at VHF to microwave frequencies where the small skin depth requires only a very thin layer of silver, making the improvement in conductivity very cost effective.

Skin effect itself is not actually combatted in these cases, but the distribution of currents near the conductor's surface makes the use of precious metals (having a lower resistivity) practical.

Recently, a method of layering non-magnetic and ferromagnetic materials with nanometer scale thicknesses has been shown to mitigate the increased resistance from skin effect for very high-frequency applications.

[citation needed] As experiments have shown, this has potential to greatly improve the efficiency of conductors operating in tens of GHz or higher.

A practical consequence is seen by users of induction cookers, where some types of stainless steel cookware are unusable because they are not ferromagnetic.

A layer of silver 3 μm thick evaporated on a piece of glass is thus an excellent conductor at such frequencies.

In copper, skin depth can be seen to fall according to the square root of frequency: In Engineering Electromagnetics, Hayt points out that in a power station a busbar for alternating current at 60 Hz with a radius larger than one-third of an inch (8 mm) is a waste of copper,[20] and in practice bus bars for heavy AC current are rarely more than half an inch (12 mm) thick except for mechanical reasons.

This effect was first noticed by Heinz London in 1940, who correctly suggested that it is due to the mean free path length of the electrons reaching the range of the classical skin depth.

- A non-energized

- B low frequency

- C middle frequency

- D high frequency

- Mn-Zn – magnetically soft ferrite

- Al – metallic aluminum

- Cu – metallic copper

- steel 410 – magnetic stainless steel

- Fe-Si – grain-oriented electrical steel

- Fe-Ni – high-permeability permalloy (80%Ni-20%Fe)