Eddy current

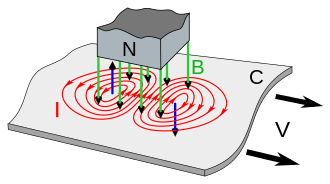

Eddy currents flow in closed loops within conductors, in planes perpendicular to the magnetic field.

This effect is employed in eddy current brakes which are used to stop rotating power tools quickly when they are turned off.

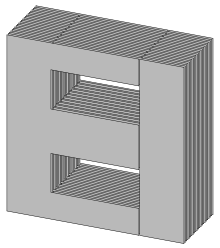

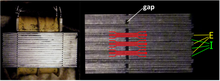

Thus eddy currents are a cause of energy loss in alternating current (AC) inductors, transformers, electric motors and generators, and other AC machinery, requiring special construction such as laminated magnetic cores or ferrite cores to minimize them.

The first person to observe eddy currents was François Arago (1786–1853), the President of the Council of Ministers of the 2nd French Republic during the brief period 10th May to June 24, 1848 (equivalent to the current position of the French Prime Minister), who was also a mathematician, physicist and astronomer.

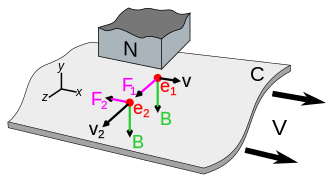

This change in magnetic flux, in turn, induces a circular electromotive force (EMF) in the sheet, in accordance with Faraday's law of induction, exerting a force on the electrons in the sheet, causing a counterclockwise circular current

Since the electrons have a negative charge, they move in the opposite direction to the conventional current shown by the arrows.

The electrons collide with the metal lattice atoms, exerting a drag force on the sheet proportional to its velocity.

As described by Ampère's circuital law, each of the circular currents in the sheet induces its own magnetic field (marked in blue arrows in the diagram).

Another way to understand the drag is to observe that in accordance with Lenz's law, the induced electromotive force must oppose the change in magnetic flux through the sheet.

Eddy currents in conductors of non-zero resistivity generate heat as well as electromagnetic forces.

The electromagnetic forces can be used for levitation, creating movement, or to give a strong braking effect.

Eddy currents can also have undesirable effects, for instance power loss in transformers.

This Joule heating reduces efficiency of iron-core transformers and electric motors and other devices that use changing magnetic fields.

Electrons cannot cross the insulating gap between the laminations and so are unable to circulate on wide arcs.

So, by Lenz's law, the magnetic field formed by the eddy current will oppose its cause.

The faster the wheels are spinning, the stronger the effect, meaning that as the train slows the braking force is reduced, producing a smooth stopping motion.

the power lost due to eddy currents per unit mass for a thin sheet or wire can be calculated from the following equation:[4]

where This equation is valid only under the so-called quasi-static conditions, where the frequency of magnetisation does not result in the skin effect; that is, the electromagnetic wave fully penetrates the material.

Another application is on some roller coasters, where heavy copper plates extending from the car are moved between pairs of very strong permanent magnets.

Electrical resistance within the plates causes a dragging effect analogous to friction, which dissipates the kinetic energy of the car.

The same technique is used in electromagnetic brakes in railroad cars and to quickly stop the blades in power tools such as circular saws.

In a varying magnetic field, the induced currents exhibit diamagnetic-like repulsion effects.

This can lift objects against gravity, though with continual power input to replace the energy dissipated by the eddy currents.

As described in the section above about eddy current brakes, a non-ferromagnetic conductor surface tends to rest within this moving field.

[8] In some coin-operated vending machines, eddy currents are used to detect counterfeit coins, or slugs.

The coin rolls past a stationary magnet, and eddy currents slow its speed.

Eddy currents are used in certain types of proximity sensors to observe the vibration and position of rotating shafts within their bearings.

These sensors are extremely sensitive to very small displacements making them well suited to observe the minute vibrations (on the order of several thousandths of an inch) in modern turbomachinery.

[clarification needed] Widespread use of such sensors in turbomachinery has led to development of industry standards that prescribe their use and application.

[9][10][11] Eddy current techniques are commonly used for the nondestructive examination (NDE) and condition monitoring of a large variety of metallic structures, including heat exchanger tubes, aircraft fuselage, and aircraft structural components.