Stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates.

In the stomach a chemical breakdown of food takes place by means of secreted digestive enzymes and gastric acid.

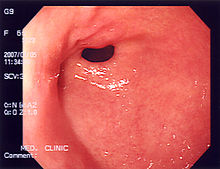

In the human digestive system, the stomach lies between the esophagus and the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine).

The stomach is surrounded by parasympathetic (inhibitor) and sympathetic (stimulant) plexuses (networks of blood vessels and nerves in the anterior gastric, posterior, superior and inferior, celiac and myenteric), which regulate both the secretory activity of the stomach and the motor (motion) activity of its muscles.

[7][8] The cardia is defined as the region following the "z-line" of the gastroesophageal junction, the point at which the epithelium changes from stratified squamous to columnar.

The two sets of gastric lymph nodes drain the stomach's tissue fluid into the lymphatic system.

The outer longitudinal layer is responsible for moving the semi-digested food towards the pylorus of the stomach through muscular shortening.

Smooth mucosa along the inside of the lesser curvature forms a passageway - the gastric canal that fast-tracks liquids entering the stomach, to the pylorus.

The corresponding specific proteins expressed in stomach are mainly involved in creating a suitable environment for handling the digestion of food for uptake of nutrients.

Sections of this gut begin to differentiate into the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, and the esophagus, and stomach form from the foregut.

In the adult, these connective structures of omentum and mesentery form the peritoneum, and act as an insulating and protective layer while also supplying organs with blood and lymph vessels as well as nerves.

In the human digestive system, a bolus (a small rounded mass of chewed up food) enters the stomach through the esophagus via the lower esophageal sphincter.

Chyme slowly passes through the pyloric sphincter and into the duodenum of the small intestine, where the extraction of nutrients begins.

Within a few moments after food enters the stomach, mixing waves begin to occur at intervals of approximately 20 seconds.

The pylorus, which holds around 30 mL of chyme, acts as a filter, permitting only liquids and small food particles to pass through the mostly, but not fully, closed pyloric sphincter.

In a process called gastric emptying, rhythmic mixing waves force about 3 mL of chyme at a time through the pyloric sphincter and into the duodenum.

Release of a greater amount of chyme at one time would overwhelm the capacity of the small intestine to handle it.

Ultimately, mixing waves incorporate this food with the chyme, the acidity of which inactivates salivary amylase and activates lingual lipase.

Since enzymes in the small intestine digest fats slowly, food can stay in the stomach for 6 hours or longer when the duodenum is processing fatty chyme.

This includes: The parietal cells of the human stomach are responsible for producing intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12.

Chyme from the stomach is slowly released into the duodenum through coordinated peristalsis and opening of the pyloric sphincter.

Salivary EGF, which also seems to be regulated by dietary inorganic iodine, also plays an important physiological role in the maintenance of oro-esophageal and gastric tissue integrity.

[37] The human stomach has receptors responsive to sodium glutamate[38] and this information is passed to the lateral hypothalamus and limbic system in the brain as a palatability signal through the vagus nerve.

[39] The stomach can also sense, independently of tongue and oral taste receptors, glucose,[40] carbohydrates,[41] proteins,[41] and fats.

In fact, the stomach and thyroid share iodine-concentrating ability and many morphological and functional similarities, such as cell polarity and apical microvilli, similar organ-specific antigens and associated autoimmune diseases, secretion of glycoproteins (thyroglobulin and mucin) and peptide hormones, the digesting and readsorbing ability, and lastly, similar ability to form iodotyrosines by peroxidase activity, where iodide acts as an electron donor in the presence of H2O2.

[47] A large number of studies have indicated that most cases of peptic ulcers, and gastritis, in humans are caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, and an association has been seen with the development of stomach cancer.

However, lampreys, hagfishes, chimaeras, lungfishes, and some teleost fish have no stomach at all, with the esophagus opening directly into the intestine.

Furthermore, in many non-human mammals, a portion of the stomach anterior to the cardiac glands is lined with epithelium essentially identical to that of the esophagus.

Anteriorly is a narrow tubular region, the proventriculus, lined by fundic glands, and connecting the true stomach to the crop.

Beyond lies the powerful muscular gizzard, lined by pyloric glands, and, in some species, containing stones that the animal swallows to help grind up food.