Slime mold

Most slime molds are terrestrial and free-living, typically in damp shady habitats such as in or on the surface of rotting wood.

A small number of species occur in regions as dry as the Atacama Desert and as cold as the Arctic; they are abundant in the tropics, especially in rainforests.

He also introduced a "Doubtful Mycetozoa" section for Plasmodiophora (now in Phytomyxea) and Labyrinthula, emphasizing their distinction from plants and fungi.

[4] In 1885, the British zoologist Ray Lankester grouped the Mycetozoa alongside the Proteomyxa as part of the Gymnomyxa in the phylum Protozoa.

[4][9] In 1969, the taxonomist R. H. Whittaker observed that slime molds were highly conspicuous and distinct within the Fungi, the group to which they were then classified.

He concurred with Lindsay S. Olive's proposal to reclassify the Gymnomycota, which includes slime molds, as part of the Protista.

[17] Most are smaller than a few centimeters, but some species may reach sizes up to several square meters, and in the case of Brefeldia maxima, a mass of up to 20 kilograms (44 lb).

The amoebae join up into a tiny multicellular slug which crawls to an open lit place and grows into a fruiting body, a sorocarp.

[29] The Labyrinthulomycetes are marine slime nets, forming labyrinthine networks of tubes in which amoeba without pseudopods can travel.

[34] Myxogastria are not limited to wet regions; 34 species are known from Saudi Arabia, living on bark, in plant litter, and rotting wood, even in deserts.

[35] In tropical rainforests of Latin America, species such as of Arcyria and Didymium are commonly epiphyllous, growing on the leaves of liverworts.

[33] Cellular slime molds are most numerous in the tropics, decreasing with latitude, but are cosmopolitan in distribution, occurring in soil even in the Arctic and the Antarctic.

The slime mold fly Epicypta testata lay its eggs within the spore mass of Enteridium lycoperdon, which the larvae feed on.

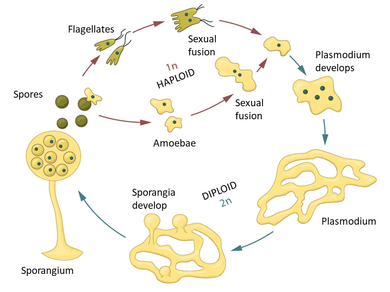

[43] Slime molds are isogamous, which means that their gametes (reproductive cells) are all the same size, unlike the eggs and sperms of animals.

They occur primarily in the humus layer of forest soils[48] and feed on bacteria but also are found in animal dung and agricultural fields.

They readily change the shape and function of parts, and may form stalks that produce fruiting bodies, releasing countless spores, light enough to be carried on the wind or on passing animals.

During the aggregation phase of their life cycle, Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae communicate with each other using traveling waves of cyclic AMP.

[57] The practical study of slime molds was facilitated by the introduction of the "moist culture chamber" by H. C. Gilbert and G. W. Martin in 1933.

[58] Slime molds can be used to teach convergent evolution, as the habit of forming a stalk with a sporangium that can release spores into the air, off the ground, has evolved repeatedly, such as in myxogastria (eukaryotes) and in myxobacteria (prokaryotes).

[59] Slime molds have been studied for their production of unusual organic compounds, including pigments, antibiotics, and anti-cancer drugs.

[60] The sporophores (fruiting bodies) of Arcyria denudata are colored red by arcyriaflavins A–C, which contain an unusual indolo[2,3-a]carbazole alkaloid ring.

Studies on Physarum polycephalum have even shown the organism to have an ability to learn and predict periodic unfavorable conditions in laboratory experiments.

It is described as a simple, efficient, and flexible way of solving optimization problems, such as finding the shortest path between nodes in a network.

The mold first densely filled the space with plasmodia, and then thinned the network to focus on efficiently connected branches.

[72][73] P. polycephalum was used in experimental laboratory approximations of motorway networks of 14 geographical areas: Australia, Africa, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Iberia, Italy, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, UK and US.

This observation has led astronomers to use simulations based on the behaviour of slime molds to inform their search for dark matter.

[77][78] In central Mexico, the false puffball Enteridium lycoperdon was traditionally used as food; it was one of the species which mushroom-collectors or hongueros gathered on trips into the forest in the rainy season.

[79] Oscar Requejo and N. Floro Andres-Rodriguez suggest that Fuligo septica may have inspired Irvin Yeaworth's 1958 film The Blob, in which a giant amoeba from space sets about engulfing people in a small American town.