Slow earthquake

[4] The causes that lead to slow earthquakes have only been theoretically investigated, by the formation of longitudinal shear cracks that were analysed using mathematical models.

[5] In other words, slow earthquakes are caused by a variety of stick-slip and creep processes intermediated between asperity-controlled brittle and ductile fracture.

As of 2013[update] some of the locations that have been recently studied for slow earthquakes include: Cascadia,[6] California, Japan, New Zealand, Mexico, and Alaska.

[13] LFEs are highly sensitive seismic events which can likely be triggered by tidal forces as well as propagating waves from distant earthquakes.

[8] Since slow slip events and their corresponding LFE signals have been recorded, none of them have been accompanied by a megathrust earthquake, however, SSEs act to increase the stress in the seismogenic zone by forcing the locked interval between the subducting and overriding plate to accommodate for down-dip movement.

Additionally, LFEs are useful for the tomographic imaging of subduction zones because their distributions accurately map the deep plate contact near the Mohorovicic discontinuity.

The discovery and understanding of LFEs at subduction zones is due in part to the fact that the seismic signatures of these events were found away from volcanoes.

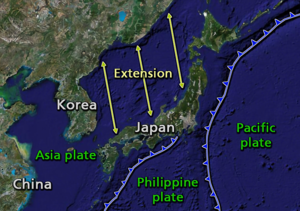

[11] LFEs and SSEs are frequently observed at subduction zones in western North America, Japan, Mexico, Costa Rica, New Zealand, as well as in shallow strike slip faults in California.

The most common method for identifying LFEs involves the correlation of the seismic record with a template constructed from confirmed LFE waveforms.

[10][12][8] Since LFEs are such subtle events and have amplitudes that are frequently drowned out by background noise, templates are built by stacking similar LFE waveforms to reduce the SNR.

Noise is reduced to such an extent that a relatively clean waveform can be searched for in the seismic record, and when correlation coefficients are deemed high enough an LFE is detected.

[13] Extracting high quality P wave data out of LFE waveforms can be quite difficult, however, and is furthermore important for accurate hypocentral depth determinations.

[10] This method does not discriminate whether or not the observed LFE was triggered at the plate interface or within the down-going slab itself, so additional geophysical analysis is required to determine where exactly the focus is located.

[22][13][10] The Cascadia subduction zone spans from northern California to about halfway up Vancouver Island and is where the Juan de Fuca, Explorer, and Gorda plates are overridden by North America.

[22] These seismic properties defining the LVZ have been interpreted as an overpressured region of the down-going slab with high pore fluid pressures.

[15][22] The presence of water at the subduction interface and its relation to the generation of LFEs is not fully understood, but hydrolytic weakening of the rock contact is likely important.

The first indicator of low frequency earthquakes in Cascadia was discovered in 1999 when an aseismic event took place at the subduction interface wherein the overriding North American plate slipped 2 centimeters south-west over a several-week period as recorded by Global Positioning System (GPS)[24] sites in British Columbia.

Upon the advent of improved processing techniques, and the discovery that LFEs form part of tremor,[11] low frequency earthquakes were widely considered a commonplace occurrence at the plate interface down-dip of the seismogenic zone in Cascadia.

The discovery of LFEs originates in Japan at the Nankai trough and is in part due to the nationwide collaboration of seismological research following the Kobe earthquake of 1995.

[20] Similar to Cascadia, these low frequency tremors occurred with slow slip events that had a recurrence interval of approximately 6 months.

[32] VLFs have been found at both the Cascadia subduction zone in western North America,[33] as well as in Japan at the Nankai trough and Ryukyu trench.