Social realism

[1] The term is sometimes more narrowly used for an art movement that flourished in the interwar period as a reaction to the hardships and problems suffered by common people after the Great Crash.

In order to make their art more accessible to a wider audience, artists turned to realist portrayals of anonymous workers as well as celebrities as heroic symbols of strength in the face of adversity.

The goal of the artists in doing so was political as they wished to expose the deteriorating conditions of the poor and working classes and hold the existing governmental and social systems accountable.

Britain's Industrial Revolution aroused concern for the poor, and in the 1870s the work of artists such as Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Frank Holl, and William Small were widely reproduced in The Graphic.

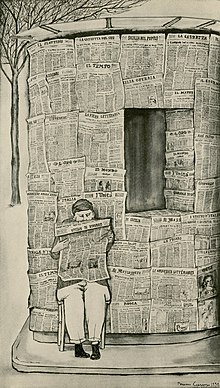

[5] In paintings, illustrations, etchings, and lithographs, Ashcan artists concentrated on portraying New York's vitality, with a keen eye on current events and the era's social and political rhetoric.

H. Barbara Weinberg of The Metropolitan Museum of Art has described the artists as documenting "an unsettling, transitional time that was marked by confidence and doubt, excitement and trepidation.

American Social Realism includes the works of such artists as those from the Ashcan School including Edward Hopper, and Thomas Hart Benton, Will Barnet, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Paul Meltsner, Romare Bearden, Rafael Soyer, Isaac Soyer, Moses Soyer, Reginald Marsh, John Steuart Curry, Arnold Blanch, Aaron Douglas, Grant Wood, Horace Pippin, Walt Kuhn, Isabel Bishop, Paul Cadmus, Doris Lee, Philip Evergood, Mitchell Siporin, Robert Gwathmey, Adolf Dehn, Harry Sternberg, Gregorio Prestopino, Louis Lozowick, William Gropper, Philip Guston, Jack Levine, Ralph Ward Stackpole, John Augustus Walker and others.

It also extends to the art of photography as exemplified by the works of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Lewis Hine, Edward Steichen, Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein, Marion Post Wolcott, Doris Ulmann, Berenice Abbott, Aaron Siskind, and Russell Lee among several others.

Santiago Martínez Delgado, Jorge González Camarena, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú Garza, and Jean Charlot, as well as several other artists participated in the movement.

Consequences of the Industrial Revolution became apparent; urban centers grew, slums proliferated on a new scale contrasting with the display of wealth of the upper classes.

Social realist photography reached a culmination in the work of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, and others for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) project, from 1935 to 1943.

Santiago Martínez Delgado, Jorge González Camarena, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú Garza, and Jean Charlot, as well as several other artists participated in the movement.

[15] After the war, although lacking attention in the art market, many social realist artists continued their careers into the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s; throughout which, artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Ben Shahn, Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Raphael Soyer, Robert Gwathmey, Antonio Frasconi, Philip Evergood, Sidney Goodman, and Aaron Berkman continued to work with social realist modalities and themes.

These murals also encouraged social realism in other Latin American countries, from Ecuador (Oswaldo Guayasamín's The Strike) to Brazil (Cândido Portinari's Coffee).

[1] In Belgium, early representatives of social realism are found in the work of 19th century artists such as Constantin Meunier and Charles de Groux.

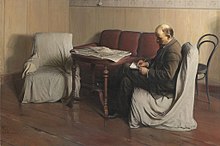

In particular, the Peredvizhniki or Wanderers group in Russia who formed in the 1860s and organized exhibitions from 1871 included many realists such as Ilya Repin and had a great influence on Russian art.

It depicted subjects of social concern; the proletariat struggle – hardships of everyday life that the working class had to put up with, and heroically emphasized the values of the loyal communist workers.

The ideology behind social realism, communicated by depicting the heroism of the working class, was to promote and spark revolutionary actions and to spread the image of optimism and the importance of productiveness.

During Joseph Stalin's reign, it was considered most important to use socialist realism as a form of propaganda in posters, as it kept people optimistic and encouraged greater productive effort, a necessity in his aim of developing Russia into an industrialized nation.

It also gave Stalin and his Communist Party greater control over Soviet culture and restricted people from expressing alternative geopolitical ideologies that differed to those represented in socialist realism.

[citation needed] Social realism in cinema found its roots in Italian neorealism, especially the films of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti and to some extent Federico Fellini.

Critic Richard Armstrong said: "Combining the objective temper and aesthetics of the documentary movement with the stars and resources of studio filmmaking, 1940s British cinema made a stirring appeal to a mass audience.

Historian Roger Manvell wrote, "As the cinemas [closed initially because of the fear of air raids] reopened, the public flooded in, searching for relief from hard work, companionship, release from tension, emotional indulgence and, where they could find them, some reaffirmation of the values of humanity.

"[28] In the postwar period, films like Passport to Pimlico (1949), The Blue Lamp (1949), and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1952) reiterated gentle patrician values, creating a tension between the camaraderie of the war years and the burgeoning consumer society.

Issues such as short-term sexual relationships, adultery, and illegitimate births flourished during the Second World War[29] and Box, who favoured realism over what he termed as "flamboyance fantasy",[30] brought these and other social issues, such as child adoption, juvenile delinquency, and displaced persons to the fore with films such as When the Bough Breaks (1947), Good-Time Girl (1948), Portrait from Life (1948), The Lost People (1949), and Boys in Brown (1949).

Films of new rapidly expanding forms of leisure by working class families in postwar Britain were also represented by Box in Holiday Camp (1947), Easy Money (1948), and A Boy, a Girl and a Bike (1949).

British auteurs like Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, and John Schlesinger brought wide shots and plain speaking to stories of ordinary Britons negotiating postwar social structures.