Sequence analysis in social sciences

Introduced in the social sciences in the 80s by Andrew Abbott,[1][2] SA has gained much popularity after the release of dedicated software such as the SQ[3] and SADI[4] addons for Stata and the TraMineR R package[5] with its companions TraMineRextras[6] and WeightedCluster.

In sociology, sequence techniques are most commonly employed in studies of patterns of life-course development, cycles, and life histories.

[18][19][20] The study of interaction patterns is increasingly centered on sequential concepts, such as turn-taking, the predominance of reciprocal utterances, and the strategic solicitation of preferred types of responses (see Conversation Analysis).

In particular, sociologists objected to the descriptive and data-reducing orientation of optimal matching, as well as to a lack of fit between bioinformatic sequence methods and uniquely social phenomena.

[25][26] The debate has given rise to several methodological innovations (see Pairwise dissimilarities below) that address limitations of early sequence comparison methods developed in the 20th century.

This focus on regularized patterns of social action has become an increasingly influential framework for understanding microsocial interaction and contact sequences, or "microsequences.

[42] This idea is also echoed in Pierre Bourdieu's concept of habitus, which emphasizes the emergence and influence of stable worldviews in guiding everyday action and thus produce predictable, orderly sequences of behavior.

[19][18][45] All of these theoretical orientations together warrant critiques of the general linear model of social reality, which as applied in most work implies that society is either static or that it is highly stochastic in a manner that conforms to Markov processes[1][46] This concern inspired the initial framing of social sequence analysis as an antidote to general linear models.

It has also motivated recent attempts to model sequences of activities or events in terms as elements that link social actors in non-linear network structures[47][48] This work, in turn, is rooted in Georg Simmel's theory that experiencing similar activities, experiences, and statuses serves as a link between social actors.

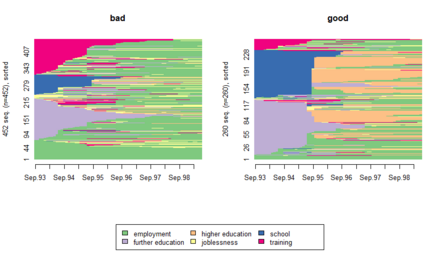

At an inter-individual level, pairwise dissimilarities and clustering appeared as the appropriate tools for revealing the heterogeneity in human development.

[34] The interest for this perspective was also promoted by the changes in individuals' life courses for cohorts born between the beginning and the end of the 20th century.

[53] Among the drivers of these dynamics, the transition to adulthood is key:[54] for more recent birth cohorts this crucial phase along individual life courses implied a larger number of events and lengths of the state spells experienced.

[55] Such complexity required to be measured to be able to compare quantitative indicators across birth cohorts[11][56] (see[57] for an extension of this questioning to populations from low- and medium income countries).

The analysis of temporal processes in the domain of political sciences[60] regards how institutions, that is, systems and organizations (regimes, governments, parties, courts, etc.)

Special importance is given to, first, the role of contexts, which confer meaning to trends and events, while shared contexts offer shared meanings; second, to changes over time in power relationships, and, subsequently, asymmetries, hierarchies, contention, or conflict; and, finally, to historical events that are able to shape trajectories, such as elections, accidents, inaugural speeches, treaties, revolutions, or ceasefires.

Depending on the unit of analysis, the sample sizes may be limited few cases (e.g., regions in a country when considering the turnover of local political parties over time) or include a few hundreds (e.g., individuals' voting patterns).

The first and most common is careers, that is, formal, mostly hierarchical positions along which individuals progress in institutional environments, such as parliaments, cabinets, administrations, parties, unions or business organizations.

[66] Finally, processes relate to non-individual entities, such as: public policies developing through successive policy stages across distinct arenas;[67] sequences of symbolic or concrete interactions between national and international actors in diplomatic and military contexts;[68][69] and development of organizations or institutions, such as pathways of countries towards democracy (Wilson 2014).

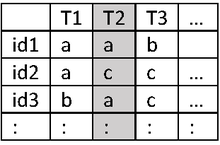

In social sciences, n is generally something between a few hundreds and a few thousands, the alphabet size remains limited (most often less than 20), while sequence length rarely exceeds 100.

Although dissimilarity-based methods play a central role in social SA, essentially because of their ability to preserve the holistic perspective, several other approaches also prove useful for analyzing sequence data.

[36] Among the most challenging, we can mention: Up-to-date information on advances, methodological discussions, and recent relevant publications can be found on the Sequence Analysis Association webpage.

Some examples of application include: Sociology Demography and historical demography Political sciences Education and learning sciences Psychology Medical research Survey methodology Geography Two main statistical computing environment offer tools to conduct a sequence analysis in the form of user-written packages: Stata and R. The first international conference dedicated to social-scientific research that uses sequence analysis methods – the Lausanne Conference on Sequence Analysis, or LaCOSA – was held in Lausanne, Switzerland in June 2012.