Social vulnerability

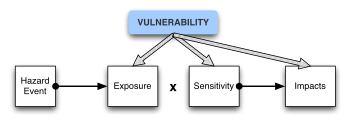

Social vulnerability refers to the inability of people, organizations, and societies to withstand adverse impacts from multiple stressors to which they are exposed.

Taking a structuralist view, Hewitt[8] defines vulnerability as being: ...essentially about the human ecology of endangerment...and is embedded in the social geography of settlements and lands uses, and the space of distribution of influence in communities and political organisation.

This contrasts with the more socially focused view of Blaikie et al.[9] who define vulnerability as the:...set of characteristics of a group or individual in terms of their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard.

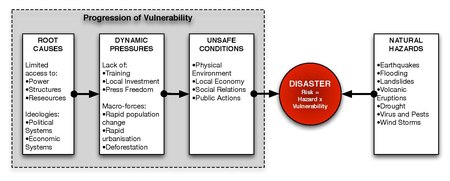

It involves a combination of factors that determine the degree to which someone's life and livelihood is at risk by a discrete and identifiable event in nature or society.

The work also showed that the greatest losses of life concentrate in underdeveloped countries, where the authors concluded that vulnerability is increasing.

Chambers put these empirical findings on a conceptual level and argued that vulnerability has an external and internal side: People are exposed to specific natural and social risk.

However, it is also important to note, that a focus limited to the stresses associated with a particular vulnerability analysis is also insufficient for understanding the impact on and responses of the affected system or its components (Mileti, 1999; Kaperson et al., 2003; White & Haas, 1974).

Inherent in such a view is the tendency to understand people as passive victims (Hewitt 1997) and to neglect the subjective and intersubjective interpretation and perception of disastrous events.

Bankoff criticises the very basis of the concept, since in his view it is shaped by a knowledge system that was developed and formed within the academic environment of western countries and therefore inevitably represents values and principles of that culture.

The desire to understand geographic, historic, and socio-economic characteristics of social vulnerability motivates much of the research being conducted around the world today.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are increasingly being used to map vulnerability, and to better understand how various phenomena (hydrological, meteorological, geophysical, social, political and economic) effect human populations.

An even greater aspiration in social vulnerability research is the search for one, broadly applicable theory, which can be applied systematically at a variety of scales, all over the world.

Climate change scientists, building engineers, public health specialists, and many other related professions have already achieved major strides in reaching common approaches.

Some social vulnerability scientists argue that it is time for them to do the same, and they are creating a variety of new forums in order to seek a consensus on common frameworks, standards, tools, and research priorities.

Disasters often expose pre-existing societal inequalities that lead to disproportionate loss of property, injury, and death (Wisner, Blaikie, Cannon, & Davis, 2004).

Minorities, immigrants, women, children, the poor, as well as people with disabilities are among those have been identified as particularly vulnerable to the impacts of disaster (Cutter et al., 2003; Peek, 2008; Stough, Sharp, Decker & Wilker, 2010).

These indicators are generated through the statistical analysis of more than 500 thousand people who are suffering from economic strain and social vulnerability and have a personal record containing 220 variables at the Red Cross database.

Psychological research by Willem Doise and colleagues shows indeed that after people have experienced a collective injustice, they are more likely to support the reinforcement of human rights.

[20] Some analyses performed by Dario Spini, Guy Elcheroth and Rachel Fasel[21] on the Red Cross' "People on War" survey shows that when individuals have direct experience with the armed conflict are less keen to support humanitarian norms.

In the future, links will be strengthened between ongoing policy and academic work to solidify the science, consolidate the research agenda, and fill knowledge gaps about causes of and solutions for social vulnerability.