Society and culture of the Han dynasty

While Han Taoists were organized into small groups chiefly concerned with achieving immortality through various means, by the mid 2nd century CE they formed large hierarchical religious societies that challenged imperial authority and viewed Laozi (fl.

Starting with Emperor Gaozu's reign, thousands of noble families, including those from the royal houses of Qi, Chu, Yan, Zhao, Han, and Wei from the Warring States period, were forcibly moved to the vicinity of the capital Chang'an.

[18] After the eunuch Shi Xian (石顯) became the Prefect of the Palace Masters of Writing (中尚書), Emperor Yuan (r. 48–33 BCE) relinquished much of his authority to him, so that he was allowed to make vital policy decisions and was respected by officials.

[53] They mostly relied on poor tenant farmers (diannong 佃農) who paid rent in the form of roughly fifty percent of their produce in exchange for land, tools, draft animals, and a small house.

While government workshops employed convicts, corvée laborers, and state-owned slaves to perform menial tasks, the master craftsman was paid a significant income for his work in producing luxury items such as bronze mirrors and lacquerwares.

This is in stark contrast to unregistered itinerant merchants who Chao Cuo (d. 154 BCE) states wore fine silks, rode in carriages pulled by fat horses, and whose wealth allowed them to associate with government officials.

[85] The official Cui Shi (催寔) (d. 170 CE) started a brewery business to help pay for his father's costly funeral, an act which was heavily criticized by his fellow gentrymen who considered this sideline occupation a shameful one for any scholar.

[116] Those who practiced occult arts of Chinese alchemy and mediumship were often employed by the government to conduct religious sacrifices, while on rare occasions—such as with Luan Da (d. 112 BCE)—an occultist might marry a princesses or be enfeoffed as a marquess.

[122] When a commoner was promoted in rank, he was granted a more honorable place in the seating arrangements of hamlet banquets, was given a greater portion of hunted game at the table, was punished less severely for certain crimes, and could become exempt from labor service obligations to the state.

[14] When the authority of the central government declined in the late Eastern Han period, many commoners living in such hamlets were forced to flee their lands and work as tenants on large estates of wealthy landowners.

[175] The historian Sima Tan (d. 110 BCE) wrote that the Legalist tradition inherited by Han from the previous Qin dynasty taught that imposing severe man-made laws which were short of kindness would produce a well-ordered society, given that human nature was innately immoral and had to be checked.

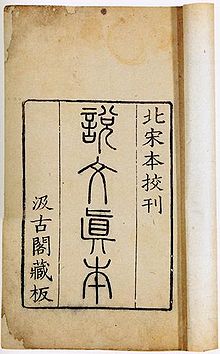

[181] Scholars such as Shusun Tong (叔孫通) began to express greater emphasis for ethical ideas espoused in 'Classicist' philosophical works such as those of Kongzi (i.e. Confucius, 551–479 BCE), an ideology anachronistically known as Confucianism.

The amalgamation of these ideas into a theological system involving earlier cosmological theories of yin and yang as well as the five phases (i.e. natural cycles which governed Heaven, Earth, and Man) was first pioneered by the official Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BCE).

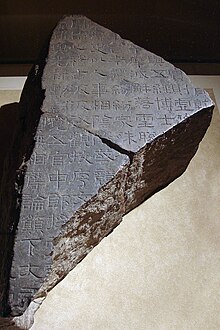

The former represented works transmitted orally after the Qin book burning of 213 BCE, and the latter was newly discovered texts alleged by Kong Anguo, Liu Xin, and others to have been excavated from the walls of Kongzi's home, displayed archaic written characters, and thus were more authentic versions.

[197] In his Balanced Discourse (Lunheng), Wang Chong (27–100 CE) argued that human life was not a coherent whole dictated by a unitary will of Heaven as in Dong's synthesis, but rather was broken down into three planes: biological (mental and physical), sociopolitical, and moral, elements which interacted with each other to produce different results and random fate.

[208] Hardy explains that this was not unique to Sima's work, as Han scholars believed encoded secrets existed in the Spring and Autumn Annals, which was deemed "a microcosm incorporating all the essential moral and historical principles by which the world operated" and future events could be prognosticated.

They express doubt about Hardy's view that Sima intended his work to be a well-planned, homogeneous model of reality, rather than a loosely connected collection of narratives which retains the original ideological biases of the various sources used.

[211] Unlike Sima's private and independent work, this history text was commissioned and sponsored by the Han court under Emperor Ming (r. 57–75 CE), who let Ban Gu use the imperial archives.

[244] Although modern scholars know of some surviving cases where Han law dealt with commerce and domestic affairs, the spheres of trade (outside the monopolies) and the family were still largely governed by age-old social customs.

[248] The philosopher Wang Fu argued that urban society exploited the contributions of food-producing farmers while able-bodied men in the cities wasted their time (among other listed pursuits) crafting miniature plaster carts, earthenware statues of dogs, horses, and human figures of singers and actors, and children's toys.

[260] People of the Han also consumed sorghum, Job's tears, taro, mallow, mustard green, melon, bottle gourd, bamboo shoot, the roots of lotus plants, and ginger.

[266] The wealthy also wore fox and badger furs, wild duck plumes, and slippers with inlaid leather or silk lining; those of more modest means could wear wool and ferret skins.

[270] Large bamboo-matted suitcases found in Han tombs contained clothes and luxury items such as patterned fabric and embroidery, common silk, damask and brocade, and the leno (or gauze) weave, all with rich colors and designs.

The spirit-soul (hun 魂) was believed to travel to the paradise of the immortals (xian 仙) while the body-soul (po 魄) remained on earth in its proper resting place so long as measures were taken to prevent it from wandering to the netherworld.

[281] The five phases was another important cycle where the elements of wood (mu 木), fire (huo 火), earth (tu 土), metal (jin 金), and water (shui 水) succeeded each other in rotation and each corresponded with certain traits of the three realms.

[281] For example, the five phases corresponded with other sets of five like the five organs (i.e. liver, heart, spleen, lungs and kidneys) and five tastes (i.e. sour, bitter, sweet, spicy, and salty), or even things like feelings, musical notes, colors, planets, calendars and time periods.

[283] Michael Loewe (retired professor from the University of Cambridge) writes that this is consistent with the gradually higher level of emphasis given to the cosmic elements of Five Phases, which were linked with the future destiny of the dynasty and its protection.

[288] Valerie Hansen writes that Han-era Daoists were organized into small groups of people who believed that individual immortality could be obtained through "breathing exercises, sexual techniques, and medical potions.

[290] Wang Chong stated that Daoists, organized into small groups of hermits largely unconcerned with the wider laity, believed they could attempt to fly to the lands of the immortals and become invincible pure men.

[289] However, a major transformation in Daoist beliefs occurred in the 2nd century CE, when large hierarchical religious societies formed and viewed Laozi as a deity and prophet who would usher in salvation for his followers.