Stellar corona

[1] Spectroscopic measurements indicate strong ionization in the corona and a plasma temperature in excess of 1000000 kelvins,[2] much hotter than the surface of the Sun, known as the photosphere.

[4] Based on his own observations of the 1806 solar eclipse at Kinderhook (New York), de Ferrer also proposed that the corona was part of the Sun and not of the Moon.

English astronomer Norman Lockyer identified the first element unknown on Earth in the Sun's chromosphere, which was called helium (from Greek helios 'sun').

French astronomer Jules Jenssen noted, after comparing his readings between the 1871 and 1878 eclipses, that the size and shape of the corona changes with the sunspot cycle.

The high temperature of the Sun's corona gives it unusual spectral features, which led some in the 19th century to suggest that it contained a previously unknown element, "coronium".

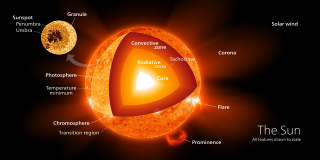

[2] The solar corona has three recognized, and distinct, sources of light that occupy the same volume: the "F-corona" (for "Fraunhofer"), the "K-corona" (for "Kontinuierlich"), and the "E-corona" (for "emission").

[6] The "F-corona" is named for the Fraunhofer spectrum of absorption lines in ordinary sunlight, which are preserved by reflection off small material objects.

The F-corona is recognized to arise from small dust grains orbiting the Sun; these form a tenuous cloud that extends through much of the solar system.

The continuum nature of the spectrum arises from Doppler broadening of the Sun's Fraunhofer absorption lines in the reference frame of the (hot and therefore fast-moving) electrons.

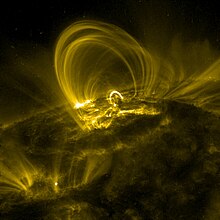

The exact mechanism by which the corona is heated is still the subject of some debate, but likely possibilities include episodic energy releases from the pervasive magnetic field and magnetohydrodynamic waves from below.

The outer edges of the Sun's corona are constantly being transported away, creating the "open" magnetic flux entrained in the solar wind.

The magnetic flux pushes the hotter photosphere aside, exposing the cooler plasma below, thus creating the relatively dark sun spots.

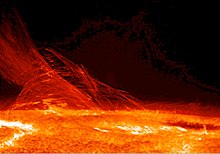

On the contrary, quiescent prominences are large, cool, dense structures which are observed as dark, "snake-like" Hα ribbons (appearing like filaments) on the solar disc.

When the plasma rises from the foot points towards the loop top, as always occurs during the initial phase of a compact flare, it is defined as chromospheric evaporation.

The plasma may cool rapidly in this region (for a thermal instability), its dark filaments obvious against the solar disk or prominences off the Sun's limb.

An explanation of the coronal heating problem remains as these structures are being observed remotely, where many ambiguities are present (i.e., radiation contributions along the line-of-sight propagation).

Large-scale structures are very long arcs which can cover over a quarter of the solar disk but contain plasma less dense than in the coronal loops of the active regions.

[14] The large-scale structure of the corona changes over the 11-year solar cycle and becomes particularly simple during the minimum period, when the magnetic field of the Sun is almost similar to a dipolar configuration (plus a quadrupolar component).

[15] Some other features of this kind are helmet streamers – large, cap-like coronal structures with long, pointed peaks that usually overlie sunspots and active regions.

The result of the Sun's differential rotation is that the active regions always arise in two bands parallel to the equator and their extension increases during the periods of maximum of the solar cycle, while they almost disappear during each minimum.

[21] A portrait, as diversified as the one already pointed out for the coronal features, is emphasized by the analysis of the dynamics of the main structures of the corona, which evolve at differential times.

These are enormous emissions of coronal material and magnetic field that travel outward from the Sun at up to 3000 km/s,[24] containing roughly 10 times the energy of the solar flare or prominence that accompanies them.

[25] The astronomical observations planned with the Einstein Observatory by Giuseppe Vaiana and his group[26] showed that F-, G-, K- and M-stars have chromospheres and often coronae much like the Sun.

However these stars do not have coronae, but the outer stellar envelopes emit this radiation during shocks due to thermal instabilities in rapidly moving gas blobs.

The matter in the external part of the solar atmosphere is in the state of plasma, at very high temperature (a few million kelvin) and at very low density (of the order of 1015 particles/m3).

The ionization state of a chemical element depends strictly on the temperature and is regulated by the Saha equation in the lowest atmosphere, but by collisional equilibrium in the optically thin corona.

Supposing that they have the same kinetic energy on average (for the equipartition theorem), electrons have a mass roughly 1800 times smaller than protons, therefore they acquire more velocity.

It is hypothesized that the reconnection and unravelling of braids can act as primary sources of heating of the active solar corona to temperatures of up to 4 million kelvin.

Measurements of the temperature of different ions in the solar wind with the UVCS instrument aboard SOHO give strong indirect evidence that there are waves at frequencies as high as 200Hz, well into the range of human hearing.

This process is called "reconnection" because of the peculiar way that magnetic fields behave in plasma (or any electrically conductive fluid such as mercury or seawater).