Solution of triangles

Applications requiring triangle solutions include geodesy, astronomy, construction, and navigation.

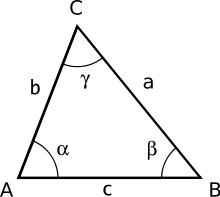

A general form triangle has six main characteristics (see picture): three linear (side lengths a, b, c) and three angular (α, β, γ).

The classical plane trigonometry problem is to specify three of the six characteristics and determine the other three.

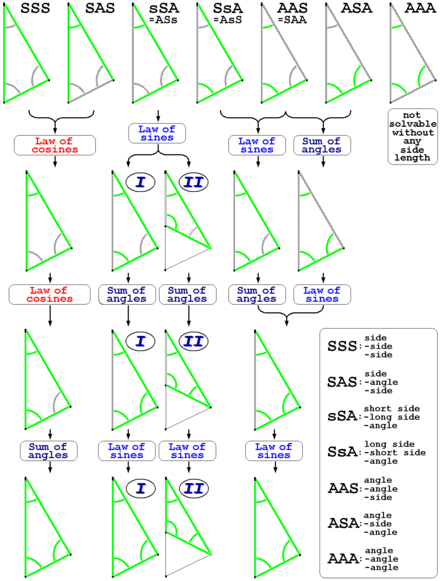

A triangle can be uniquely determined in this sense when given any of the following:[1][2] For all cases in the plane, at least one of the side lengths must be specified.

If only the angles are given, the side lengths cannot be determined, because any similar triangle is a solution.

The standard method of solving the problem is to use fundamental relations.

There are other (sometimes practically useful) universal relations: the law of cotangents and Mollweide's formula.

To find the angles α, β, the law of cosines can be used:[3]

Some sources recommend to find angle β from the law of sines but (as Note 1 above states) there is a risk of confusing an acute angle value with an obtuse one.

Another method of calculating the angles from known sides is to apply the law of cotangents.

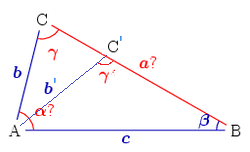

This case is not solvable in all cases; a solution is guaranteed to be unique only if the side length adjacent to the angle is shorter than the other side length.

The equation for the angle γ can be implied from the law of sines:[5]

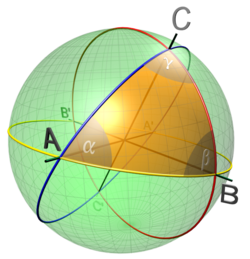

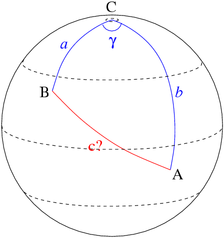

The general spherical triangle is fully determined by three of its six characteristics (3 sides and 3 angles).

For example, the sum of the three angles α + β + γ depends on the size of the triangle.

The triangle's angles are computed using the spherical law of cosines:

The angles α, β can be calculated as above, or by using Napier's analogies:

This problem arises in the navigation problem of finding the great circle between two points on the earth specified by their latitude and longitude; in this application, it is important to use formulas which are not susceptible to round-off errors.

where the signs of the numerators and denominators in these expressions should be used to determine the quadrant of the arctangent.

The angle γ can be found from the spherical law of sines:

First we determine the angle γ using the spherical law of cosines:

We can find the two unknown sides from the spherical law of cosines (using the calculated angle γ):

If the angle for the side a is acute and α > β, another solution exists:

Such a spherical triangle is fully defined by its two elements, and the other three can be calculated using Napier's Pentagon or the following relations.

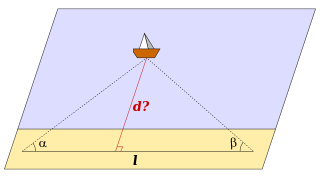

Let α, β be the angles between the baseline and the direction to the ship.

From the formulae above (ASA case, assuming planar geometry) one can compute the distance as the triangle height:

and insert this into the AAS formula for the right subtriangle that contains the angle α and the sides b and d:

(The planar formula is actually the first term of the Taylor expansion of d of the spherical solution in powers of ℓ.)

The angles α, β are defined by observation of familiar landmarks from the ship.

As another example, if one wants to measure the height h of a mountain or a high building, the angles α, β from two ground points to the top are specified.

To calculate the distance between two points on the globe, we consider the spherical triangle ABC, where C is the North Pole.