Euclidean geometry

Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms (postulates) and deducing many other propositions (theorems) from these.

This is in contrast to analytic geometry, introduced almost 2,000 years later by René Descartes, which uses coordinates to express geometric properties by means of algebraic formulas.

Euclidean geometry is an axiomatic system, in which all theorems ("true statements") are derived from a small number of simple axioms.

[4] Near the beginning of the first book of the Elements, Euclid gives five postulates (axioms) for plane geometry, stated in terms of constructions (as translated by Thomas Heath):[5] Although Euclid explicitly only asserts the existence of the constructed objects, in his reasoning he also implicitly assumes them to be unique.

They aspired to create a system of absolutely certain propositions, and to them, it seemed as if the parallel line postulate required proof from simpler statements.

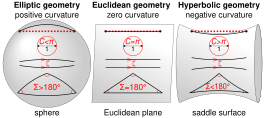

It is now known that such a proof is impossible since one can construct consistent systems of geometry (obeying the other axioms) in which the parallel postulate is true, and others in which it is false.

[12] Its name may be attributed to its frequent role as the first real test in the Elements of the intelligence of the reader and as a bridge to the harder propositions that followed.

Because of Euclidean geometry's fundamental status in mathematics, it is impractical to give more than a representative sampling of applications here.

As suggested by the etymology of the word, one of the earliest reasons for interest in and also one of the most common current uses of geometry is surveying.

Certain practical results from Euclidean geometry (such as the right-angle property of the 3-4-5 triangle) were used long before they were proved formally.

[23] He proved equations for the volumes and areas of various figures in two and three dimensions, and enunciated the Archimedean property of finite numbers.

Also in the 17th century, Girard Desargues, motivated by the theory of perspective, introduced the concept of idealized points, lines, and planes at infinity.

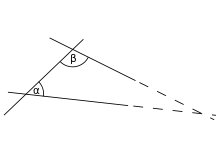

For example, the problem of trisecting an angle with a compass and straightedge is one that naturally occurs within the theory, since the axioms refer to constructive operations that can be carried out with those tools.

However, centuries of efforts failed to find a solution to this problem, until Pierre Wantzel published a proof in 1837 that such a construction was impossible.

In the early 19th century, Carnot and Möbius systematically developed the use of signed angles and line segments as a way of simplifying and unifying results.

[28] In the 1840s William Rowan Hamilton developed the quaternions, and John T. Graves and Arthur Cayley the octonions.

Hyper-tetrahedron 5-point Hyper-octahedron 8-point Hyper-cube 16-point 24-point Hyper-icosahedron 120-point Hyper-dodecahedron 600-point Schläfli performed this work in relative obscurity and it was published in full only posthumously in 1901.

In the 19th century, it was also realized that Euclid's ten axioms and common notions do not suffice to prove all of the theorems stated in the Elements.

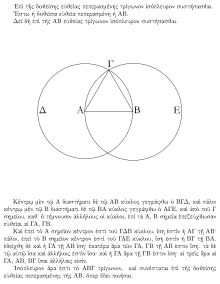

The very first geometric proof in the Elements, shown in the figure above, is that any line segment is part of a triangle; Euclid constructs this in the usual way, by drawing circles around both endpoints and taking their intersection as the third vertex.

Starting with Moritz Pasch in 1882, many improved axiomatic systems for geometry have been proposed, the best known being those of Hilbert,[32] George Birkhoff,[33] and Tarski.

[34] Einstein's theory of special relativity involves a four-dimensional space-time, the Minkowski space, which is non-Euclidean.

[35] For example, if a triangle is constructed out of three rays of light, then in general the interior angles do not add up to 180 degrees due to gravity.

A relatively weak gravitational field, such as the Earth's or the Sun's, is represented by a metric that is approximately, but not exactly, Euclidean.

They were later verified by observations such as the slight bending of starlight by the Sun during a solar eclipse in 1919, and such considerations are now an integral part of the software that runs the GPS system.

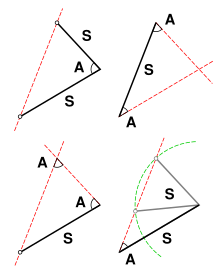

Euclid's proofs depend upon assumptions perhaps not obvious in Euclid's fundamental axioms,[37] in particular that certain movements of figures do not change their geometrical properties such as the lengths of sides and interior angles, the so-called Euclidean motions, which include translations, reflections and rotations of figures.

The ambiguous character of the axioms as originally formulated by Euclid makes it possible for different commentators to disagree about some of their other implications for the structure of space, such as whether or not it is infinite[40] (see below) and what its topology is.

[42] Later ancient commentators, such as Proclus (410–485 CE), treated many questions about infinity as issues demanding proof and, e.g., Proclus claimed to prove the infinite divisibility of a line, based on a proof by contradiction in which he considered the cases of even and odd numbers of points constituting it.

[43] At the turn of the 20th century, Otto Stolz, Paul du Bois-Reymond, Giuseppe Veronese, and others produced controversial work on non-Archimedean models of Euclidean geometry, in which the distance between two points may be infinite or infinitesimal, in the Newton–Leibniz sense.

[44] Fifty years later, Abraham Robinson provided a rigorous logical foundation for Veronese's work.

Euclid avoided such discussions, giving, for example, the expression for the partial sums of the geometric series in IX.35 without commenting on the possibility of letting the number of terms become infinite.