Somatic marker hypothesis

[3] In contrast, the somatic marker hypothesis proposes that emotions play a critical role in the ability to make fast, rational decisions in complex and uncertain situations.

Frontal lobe damage, particularly to the vmPFC, results in impaired abilities to organize and plan behavior and learn from previous mistakes, without affecting intellect in terms of working memory, attention, and language comprehension and expression.

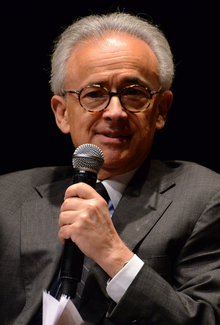

This led Antonio Damasio to hypothesize that decision-making deficits following vmPFC damage result from the inability to use emotions to help guide future behavior based on past experiences.

[1] Physiological changes (such as muscle tone, heart rate, endocrine activity, posture, facial expression, and so forth) occur in the body and are relayed to the brain where they are transformed into an emotion that tells the individual something about the stimulus that they have encountered.

When making subsequent decisions, these somatic markers and their evoked emotions are consciously or unconsciously associated with their past outcomes, and influence decision-making in favor of some behaviors instead of others.

When a somatic marker associated with the negative outcome is perceived, the person may feel sad, which acts as an internal alarm to warn the individual to avoid that course of action.

[7] In an effort to produce a simple neuropsychological tool that would assess deficits in emotional processing, decision-making, and social skills of OMPFC-lesioned individuals, Bechara and collaborators created the Iowa gambling task.

[9] Since the Iowa gambling task measures participants' quickness in "developing anticipatory emotional responses to guide advantageous choices",[10] it is helpful in testing the somatic marker hypothesis.

[15] Neuroimaging studies utilizing fMRI indicate that drug-related stimuli have the ability to activate brain regions involved in emotional evaluation and reward processing.

Damasio's notion of the as-if experience dependent feedback route,[1][17] whereby bodily responses are re-represented utilizing the somatosensory cortex (postcentral gyrus), also proposes an inefficient method of affecting explicit behavior.

[18] Reinforcement association located in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala, where the incentive value of stimuli is decoded, is sufficient to elicit emotion-based learning and to affect behavior via, for example, the orbitofrontal-striatal pathway.

First, the claim that it assesses implicit learning as the reward/punishment design is inconsistent with data showing accurate knowledge of the task possibilities[21] and that mechanisms such as working-memory appear to have a strong influence.

Furthermore, although the somatic marker hypothesis has accurately identified many of the brain regions involved in decision-making, emotion, and body-state representation, it has failed to clearly demonstrate how these processes interact at a psychological and evolutionary level.

Additionally, causal tests of the somatic marker hypothesis could be practiced more insistently in a greater range of populations with altered peripheral feedback, like on patients with facial paralysis.

Until a wider range of empirical approaches are employed in order to test the somatic marker hypothesis, it appears that the framework is simply an intriguing idea that is in need of some better supporting evidence.

Despite these issues, the somatic marker hypothesis and the Iowa gambling task reestablish the notion that emotion has the potential to be a benefit as well as a problem during the decision-making process in humans.