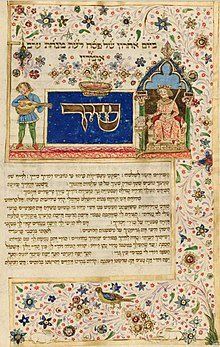

Song of Songs

Unlike most books in the Hebrew Bible, it does not focus on laws, covenants, or divine worship, but instead is erotic poetry, in which lovers express passionate desire, exchange compliments, and invite one another to enjoy.

[5] Marvin H. Pope described the Song as a celebration of sexual love, influenced by ancient fertility rituals, linked to death and liberation, and "suggestive of orgiastic revelry.”[6] Its authorship, date, and origins remain uncertain, with scholars debating its unity, structure, and possible influences from Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek love poetry.

In modern Judaism, the Song is read on the Sabbath during the Passover, which marks both the beginning of the grain-harvest and the commemoration of the Exodus from Egypt.

[9] Beyond this, however, there appears to be little agreement: attempts to find a chiastic structure have not found acceptance, and analyses dividing the book into units have employed various methods, yielding diverse conclusions.

[10] The following indicative schema is from Kugler and Hartin's An Introduction to The Bible:[11] The introduction calls the poem "the song of songs",[12] a phrase that follows an idiomatic construction commonly found in Scriptural Hebrew to indicate the object's status as the greatest and most beautiful of its class (as in Holy of Holies).

[14] The poem proper begins with the woman's expression of desire for her lover and her self-description to the "daughters of Jerusalem": she insists on her sun-born blackness, likening it to the "tents of Kedar" (nomads) and the "curtains of Solomon".

[15] The woman again addresses the daughters of Jerusalem, describing her fervent and ultimately successful search for her lover through the night-time streets of the city.

[15] The man describes his beloved: Her eyes are like doves, her hair is like a flock of goats, her teeth like shorn ewes, and so on from face to breasts.

The images are the same as those used elsewhere in the poem, but with an unusually dense use of place-names, e.g., pools of Hebron, gate of Bath-rabbim, tower of Damascus, etc.

[18] The most reliable evidence for its date is its language: Aramaic gradually replaced Hebrew after the end of the Babylonian exile in the late 6th century BCE, and the evidence of vocabulary, morphology, idiom and syntax clearly point to a late date, centuries after King Solomon to whom it is traditionally attributed.

Those who see it as an anthology or collection point to the abrupt shifts of scene, speaker, subject matter and mood, and the lack of obvious structure or narrative.

Those who hold it to be a single poem point out that it has no internal signs of composite origins, and view the repetitions and similarities among its parts as evidence of unity.

[34] The Song was accepted into the Jewish canon of scripture and was understood as "an allegory for the love between God and Israel", a view "dominant for a thousand years and more".

[36] Canonicity was tied to its attribution to Solomon, and based on an allegorical reading where the subject matter was taken to be not sexual desire but God's love for Israel.

Her beloved was identified with the male sephira Tiferet, the "Holy One Blessed be He", a central principle in the beneficent heavenly flow of divine emotion.

The text thus became a description, depending on the aspect, of the creation of the world, the passage of Shabbat, the covenant with Israel, and the coming of the Messianic age.

In modern Judaism, certain verses from the Song are read on Shabbat eve or at Passover, which marks the beginning of the grain harvest as well as commemorating the Exodus from Egypt, to symbolize the love between the Jewish people and their God.

[8] The Christian church's interpretation of the Song as evidence of God's love for his people, both collectively and individually, began with Origen.

In them, he compares the bride to the soul and the invisible groom to God: the finite soul is incessantly reaching out towards the infinite God and remains continually disappointed in this life due to the failure to achieve ecstatic union with the beloved, a vision which enraptures and can be achieved fully and perfectly only in life after death.

[53] In modern times the poem has attracted the attention of feminist biblical critics, with Phyllis Trible's foundational "Depatriarchalizing in Biblical Interpretation" treating it as an exemplary text, and the Feminist Companion to the Bible series edited by Athalya Brenner and Carole Fontaine devoting two volumes to it.

[54][55] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints specifically rejects the Song of Solomon as inspired scripture.

In his book Demystifying Islam, Muslim apologist Harris Zafar argues that the last word (Hebrew: מַחֲּמַדִּים, romanized: maḥămaddîm, lit.