Sound barrier

[3][4] The term sound barrier is still sometimes used today to refer to aircraft approaching supersonic flight in this high drag regime.

In 1947, American test pilot Chuck Yeager demonstrated that safe flight at the speed of sound was achievable in purpose-designed aircraft, thereby breaking the barrier.

Some paleobiologists report that computer models of their biomechanical capabilities suggest that certain long-tailed dinosaurs such as Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus could flick their tails at supersonic speeds, creating a cracking sound.

This speed limitation led to research into jet engines, notably by Frank Whittle in England and Hans von Ohain in Germany.

Flying the Mitsubishi Zero, pilots sometimes flew at full power into terrain because the rapidly increasing forces acting on the control surfaces of their aircraft overpowered them.

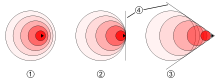

All of these effects, although unrelated in most ways, led to the concept of a "barrier" making it difficult for an aircraft to exceed the speed of sound.

[10] Erroneous news reports caused most people to envision the sound barrier as a physical "wall," which supersonic aircraft needed to "break" with a sharp needle nose on the front of the fuselage.

[12] Before the introduction of Mach meters, accurate measurements of supersonic speeds could only be made remotely, normally using ground-based instruments.

The Spitfire, a photo-reconnaissance variant, the Mark XI, fitted with an extended "rake type" multiple pitot system, was flown by Squadron Leader J. R. Tobin to this speed, corresponding to a corrected true airspeed (TAS) of 606 mph.

[14] In a subsequent flight, Squadron Leader Anthony Martindale achieved Mach 0.92, but it ended in a forced landing after over-revving damaged the engine.

[18] In 1999, Mutke enlisted the help of Professor Otto Wagner of the Munich Technical University to run computational tests to determine whether the aircraft could break the sound barrier.

"[17] One bit of evidence presented by Mutke is on page 13 of the "Me 262 A-1 Pilot's Handbook" issued by Headquarters Air Materiel Command, Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio as Report No.

The project resulted in the development of the prototype Miles M.52 turbojet-powered aircraft, which was designed to reach 1,000 mph (417 m/s; 1,600 km/h) (over twice the existing speed record) in level flight, and to climb to an altitude of 36,000 ft (11 km) in 1 minute 30 seconds.

Conventional control surfaces became ineffective at the high subsonic speeds then being achieved by fighters in dives, due to the aerodynamic forces caused by the formation of shockwaves at the hinge and the rearward movement of the centre of pressure, which together could override the control forces that could be applied mechanically by the pilot, hindering recovery from the dive.

Initially, the aircraft was to use Frank Whittle's latest engine, the Power Jets W.2/700, with which it would only reach supersonic speed in a shallow dive.

[33] The Bell X-1, the first US crewed aircraft built to break the sound barrier, was visually similar to the Miles M.52 but with a high-mounted horizontal tail to keep it clear of the wing wake.

It was in the X-1 that Chuck Yeager became the first person to break the sound barrier in level flight on 14 October 1947, flying at an altitude of 45,000 ft (13.7 km).

George Welch made a plausible but officially unverified claim to have broken the sound barrier on 1 October 1947, while flying an XP-86 Sabre.

Although evidence from witnesses and instruments strongly imply that Welch achieved supersonic speed, the flights were not properly monitored and are not officially recognized.

As a result of the X-1's initial supersonic flight, the National Aeronautics Association voted its 1947 Collier Trophy to be shared by the three main participants in the program.

[35] Jackie Cochran was the first woman to break the sound barrier, which she did on 18 May 1953, piloting a plane borrowed from the Royal Canadian Air Force, with Yeager accompanying her.

[36] On December 3, 1957, Margaret Chase Smith became the first woman in Congress to break the sound barrier, which she did as a passenger in an F-100 Super Sabre piloted by Air Force Major Clyde Good.

[39] As the science of high-speed flight became more widely understood, a number of changes led to the eventual understanding that the "sound barrier" is easily penetrated, with the right conditions.

By the 1950s, many combat aircraft could routinely break the sound barrier in level flight, although they often suffered from control problems when doing so, such as Mach tuck.

At a military test facility at Muroc Air Force Base (now Edwards AFB), California, it reached a peak speed of 1,019 mph (1,640 km/h) before jumping the rails.

The vehicle, called the ThrustSSC ("Super Sonic Car"), captured the record 50 years and one day after Yeager's first supersonic flight.

Baumgartner's feat also marked the 65th anniversary of U.S. test pilot Chuck Yeager's successful attempt to break the sound barrier in an aircraft.

[45] Baumgartner landed in eastern New Mexico after jumping from a world record 128,100 feet (39,045 m), or 24.26 miles, and broke the sound barrier as he traveled at speeds up to 833.9 mph (1342 km/h, or Mach 1.26).

[46] However, because Eustace's jump involved a drogue parachute, while Baumgartner's did not, their vertical speed and free-fall distance records remain in different categories.

[47][48] David Lean directed The Sound Barrier, a fictionalized retelling of the de Havilland DH 108 test flights.

- Subsonic

- Mach 1

- Supersonic

- Shock wave