South Sea Company

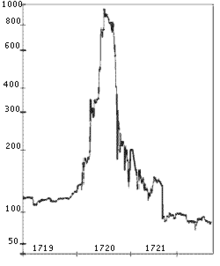

However, Company stock rose greatly in value as it expanded its operations dealing in government debt, and peaked in 1720 before suddenly collapsing to little above its original flotation price.

A number of politicians were disgraced, and people found to have profited immorally from the company had personal assets confiscated proportionate to their gains (most had already been rich and remained so).

At the time of these events, the Bank of England was also a private company dealing in national debt, and the crash of its rival confirmed its position as banker to the British government.

Harley came prepared, with detailed accounts describing the situation of the national debt, which was customarily a piecemeal arrangement, with each government department borrowing independently as the need arose.

The committee included Harley himself, the two Auditors of the Imprests (whose task was to investigate government spending), Edward Harley (the Chancellor's brother), Paul Foley (the Chancellor's brother-in-law), the Secretary of the Treasury, William Lowndes (who had had significant responsibility for reminting the entire debased British coinage in 1696) and John Aislabie (who represented the October Club, a group of about 200 MPs who had agreed to vote together).

[14] The company created a coat of arms with the motto A Gadibus usque ad Auroram ("from Cadiz to the dawn", from Juvenal, Satires, 10) and rented a large house in the City of London as its headquarters.

The task of the Company Secretary was to oversee trading activities; the Accountant, Grigsby, was responsible for registering and issuing stock; and the Cashier, Robert Knight, acted as Blunt's personal assistant at a salary of £200 per annum.

Britain was permitted to open offices in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Cartagena, Havana, Panama, Portobello and Vera Cruz to arrange the Atlantic slave trade.

The new King George I and the Prince of Wales both had large holdings in the company, as did some prominent Whig politicians, including James Craggs the Elder, the Earl of Halifax and Sir Joseph Jekyll.

Law's remarkable success was known in financial circles throughout Europe, and now came to inspire Blunt and his associates to make greater efforts to grow their own concerns.

[23] In February 1719 Craggs explained to the House of Commons a new scheme for improving the national debt by converting the annuities issued after the 1710 lottery into South Sea stock.

[24] In March there was an abortive attempt to restore the Old Pretender, James Edward Stuart, to the throne of Britain, with a small landing of troops in Scotland.

The Sword Blade company spread a rumour that the Pretender had been captured, and the general euphoria induced the South Sea share price to rise from £100, where it had been in the spring, to £114.

Shares backed by national debt were considered a safe investment and a convenient way to hold and move money, far easier and safer than metal coins.

This avoided the risk that debt might become repayable at some future point just when the government needed to borrow more, and could be forced into paying higher interest rates.

This peak encouraged people to start to sell; to counterbalance this the company's directors ordered their agents to buy, which succeeded in propping the price up at around £750.

Its success caused a country-wide frenzy—herd behavior[6]—as all types of people, from peasants to lords, developed a feverish interest in investing: in South Seas primarily, but in stocks generally.

Company failures now extended to banks and goldsmiths, as they could not collect loans made on the stock, and thousands of individuals were ruined, including many members of the British elite.

[citation needed] The newly appointed First Lord of the Treasury, Robert Walpole, successfully restored public confidence in the financial system.

In the process, Walpole won plaudits as the savior of the financial system while establishing himself as the dominant figure in British politics; historians credit him for rescuing the Whig government, and indeed the Hanoverian dynasty, from total disgrace.

[37][38][39] Joseph Spence wrote that Lord Radnor reported to him "When Sir Isaac Newton was asked about the continuance of the rising of South Sea stock ...

After Philip V became the King of Spain, Britain obtained at the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht the rights to the slave trade to the Spanish Indies (or Asiento de Negros) for 30 years.

To increase the profitability, the Asiento contract included the right to send one yearly 500-ton ship to the fairs at Portobello and Veracruz loaded with duty-free merchandises, called the Navío de Permiso.

The Government of Spain complained of the illegal trade, failure of the company to present its accounts as stipulated by the contract, and non-payment of the King's share of the profits.

These claims were a major cause of deteriorating relations between the two countries in 1738; and although the Prime Minister Walpole opposed war, there was strong support for it from the King, the House of Commons, and a faction in his own Cabinet.

The break-up of relations between the South Sea Company and the Spanish Government was a prelude to the Guerra del Asiento, as the first Royal Navy fleets departed in July 1739 for the Caribbean, prior to the declaration of war, which lasted from October 1739 until 1748.

[50] The slave Asiento contract of 1713 granted a permit to send one vessel of 500 tons per year, loaded with duty-free merchandise to be sold at the fairs of New Spain, Cartagena and Portobello.

In 1722 Henry Elking published a proposal, directed at the governors of the South Sea Company, that they should resume the "Greenland Trade" and send ships to catch whales in the Arctic.

[57] Other costs were badly controlled and the catches remained disappointingly few, even though the company was sending up to 25 ships to Davis Strait and the Greenland seas in some years.

[59] In spite of the extended duty-free concessions, and the prospect of real subsidies as well, the Court and Directors of the South Sea Company decided that they could not expect to make profits from Arctic whaling.