Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The invasion started a series of events that would ultimately pressure Brezhnev to establish a state of détente with U.S. President Richard Nixon in 1972 just months after the latter's historic visit to the PRC.

In June 1967, a small fraction of the Czech writer's union sympathized with radical socialists, specifically Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, Jan Procházka, Antonín Jaroslav Liehm, Pavel Kohout and Ivan Klíma.

[21] Leonid Brezhnev and the leadership of the Warsaw Pact countries were worried that the unfolding liberalizations in Czechoslovakia, including the ending of censorship and political surveillance by the secret police, would be detrimental to their interests.

The first such fear was that Czechoslovakia would defect from the Eastern Bloc, injuring the Soviet Union's position in a possible Third World War with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

[25] According to documents from the Ukrainian Archives, compiled by Mark Kramer, KGB chairman Yuri Andropov and Communist Party of Ukraine leaders Petro Shelest and Nikolai Podgorny were the most vehement proponents of military intervention.

As President Antonín Novotný was losing support, Alexander Dubček, First Secretary of the regional Communist Party of Slovakia, and economist Ota Šik challenged him at a meeting of the Central Committee.

[citation needed] When the KSČ Presidium member Josef Smrkovský was interviewed in a Rudé Právo article, entitled "What Lies Ahead", he insisted that Dubček's appointment at the January Plenum would further the goals of socialism and maintain the working class nature of the Communist Party.

The programme was based on the view that "Socialism cannot mean only liberation of the working people from the domination of exploiting class relations, but must make more provisions for a fuller life of the personality than any bourgeois democracy.

[40] Radical elements became more vocal: anti-Soviet polemics appeared in the press (after the abolishment of censorship was formally confirmed by law of 26 June 1968),[38] the Social Democrats began to form a separate party, and new unaffiliated political clubs were created.

[53][54] Discussions on the current state of communism and abstract ideas such as freedom and identity were also becoming more common; soon, non-party publications began appearing, such as the trade union daily Práce (Labour).

[55] The press, the radio, and the television also contributed to these discussions by hosting meetings where students and young workers could ask questions of writers such as Goldstucker, Pavel Kohout and Jan Procházka and political victims such as Josef Smrkovský, Zdeněk Hejzlar and Gustáv Husák.

[24] However, the main agreements were reached at the meetings of the “fours” - Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin, Nikolai Podgorny, Mikhail Suslov - Dubček, Ludvík Svoboda, Oldřich Černík and Josef Smrkovský.

The KSČ delegates reaffirmed their loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and promised to curb "anti-socialist" tendencies, prevent the revival of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and control the press by the re-imposition of a higher level of censorship.

The Soviet Union's policy of compelling the socialist governments of its satellite states to subordinate their national interests to those of the Eastern Bloc (through military force if needed) became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine.

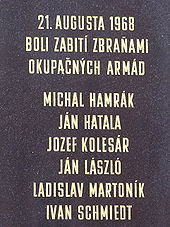

[64] At approximately 11 pm on 20 August 1968,[65] Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria,[66] Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia.

They quickly secured the airport and prepared the way for the huge forthcoming airlift, in which Antonov An-12 transport aircraft began arriving and unloading Soviet Airborne Forces equipped with artillery and light tanks.

In the early 1990s, however, the Russian government gave the new Czechoslovak President, Václav Havel, a copy of a letter of invitation addressed to Soviet authorities and signed by KSČ members Biľak, Švestka, Kolder, Indra, and Kapek.

[76] A 1992 Izvestia article claimed that candidate Presidium member Antonin Kapek gave Brezhnev a letter at the Soviet-Czechoslovak Čierna and Tisou talks in late July which appealed for "fraternal help".

A second letter was supposedly delivered by Biľak to Ukrainian Party leader Petro Shelest during the August Bratislava conference "in a lavatory rendezvous arranged through the KGB station chief".

[76] When these men had managed to convince a majority of the Presidium (six of eleven voting members) to side with them against Alexander Dubček's reformists, they asked the USSR to launch a military invasion.

Dubček's concealment of such important letters, and his unwillingness to keep his promises would lead to a vote of confidence which the now conservative majority would win, seizing power, and issue a request for Soviet assistance in preventing a counterrevolution.

[77] With this plan in mind, the 16 to 17 August Soviet Politburo meeting unanimously passed a resolution to "provide help to the Communist Party and people of Czechoslovakia through military force".

After days of negotiations, all members of the Czechoslovak delegation (including all the highest-ranked officials President Svoboda, First Secretary Dubček, Prime Minister Černík and Chairman of the National Assembly Smrkovský) but one (František Kriegel)[79] accepted the "Moscow Protocol", and signed their commitment to its fifteen points.

After the USSR used photographs of these discussions as proof that the invasion troops were being greeted amicably, secret Czechoslovak broadcasting stations discouraged the practice, reminding the people that "pictures are silent.

[86] Another common explanation is that, due to the fact that most of Czech society was middle class, the cost of continued resistance meant giving up a comfortable lifestyle, which was too high a price to pay.

Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of its liberal members, and dismissed the professional and intellectual elites who openly expressed disagreement with the political turnaround from public offices and jobs.

Only three years earlier, US delegates to the UN had insisted that the overthrow of the leftist government of the Dominican Republic, as part of Operation Power Pack, was an issue to be worked out by the Organization of American States (OAS) without UN interference.

In addition to her own personnel, an attempt was made to evacuate a group of 150 American high school students stuck in the invasion who had been on a summer abroad trip studying Russian in the (then) USSR and affiliated countries.

It was characterized by initial restoration of the conditions prevailing before the reform period led by Dubček, first of all, the firm rule of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and subsequent preservation of this new status quo.

[113] František Šebej, the Slovak chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National Council, stated that "They describe it as brotherly help aimed to prevent an invasion by NATO and fascism.

For your freedom and ours